Pál Huszár, Walburga Habsburg Douglas and Georg von Habsburg

at the event of the Otto von Habsburg Foundation, Pannonhalma, 14 July 2019.

Pál Huszár was born in Várpalota in 1941, and apart from his time in university, his whole life was connected to his immediate neighbourhood, the small town in Veszprém County and the surrounding area. After changing his career from high school teacher to university professor around the fall of communism, he helped to organise the Department of German Language and Literature at the University in Veszprém, and until his final years, was teaching at the Reformed Theological Academy of Pápa, where, in addition to lectures on ecclesiastical and cultural history, he conveyed his love of the German language to the younger generation of pastors.

Uncle Pali was a unique fixture of academic life and the Hungarian Reformed Church. His eloquent addresses and his ever-elegant appearance endowed him with a distinctive character that, at the same time, was free of any anachronism. As an intellectual of the Hungarian Reformed Church, he was aware that even in modern circumstances, we must preserve the values on which we can continue to build in the 21st century.

For him, the spirit and identity of Pannonia were not merely an inspiration but also a community of support. Throughout his life, he contributed significantly to the creation and development of higher education and the continuation of the Reformed faith in Transdanubia, while his public activities were always aimed at serving regional interests.

His heroes included the reformer John Calvin of Geneva and his Hungarian followers, while, after the change of regime, his commitment to the broader res publica Christiana, his country, and Europe brought him towards the Archduke and the Pan-European movement. It is apparent from his correspondence with Otto von Habsburg that, as a historian and a public figure determined to do his part for the country, he was well aware—and it is perhaps worth emphasising on the 20th anniversary of the accession—that the guarantee for the Hungary’s progress laid in joining the European Union.

“On the occasion of our shared joy, I would like to express my deepest respect and gratitude to Your Highness for the many decades of effort you have actively contributed to this heartwarming event. I believe I can convey to Your Highness the most sincere thanks of many of my compatriots for this delightful moment. I sincerely thank Your Highness for representing us with unfailing loyalty and Christian devotion during the long and dark years of despair and for having sought to secure a place for us in the house of a united Europe. I salute the “empty” seat in the European Parliament; I commend you for your courageous and consistent support for our cause while I rejoice in spirit with Your Highness at the hopeful successes of our nation.”

Nevertheless, beyond this justified elation, he was also aware of the challenges, including the diminishing role of Christianity in defining the image of the EU. For him, as for Otto von Habsburg, the idea of a Christian Europe was more than a political slogan: he considered these values to be decisive in shaping the political, social and intellectual architecture of the continent.

“In light of all this, I have faith and conviction that the activities of the Pan-European Union will remain necessary even after the enlargement of the European Union since we must do our utmost to shape the European Union according to the spirit—or should I say the spirituality—of the Pan-European Union. I maintain that we need a Christian Europe because “excluding” God from the life of Europe would lead to unforeseeable consequences, to catastrophes. I write this “creedal statement” with a profound sense of responsibility and, equally, with pride because I know that this conviction has always guided the activities of Your Highness as well and that God has blessed and crowned your efforts with success.”

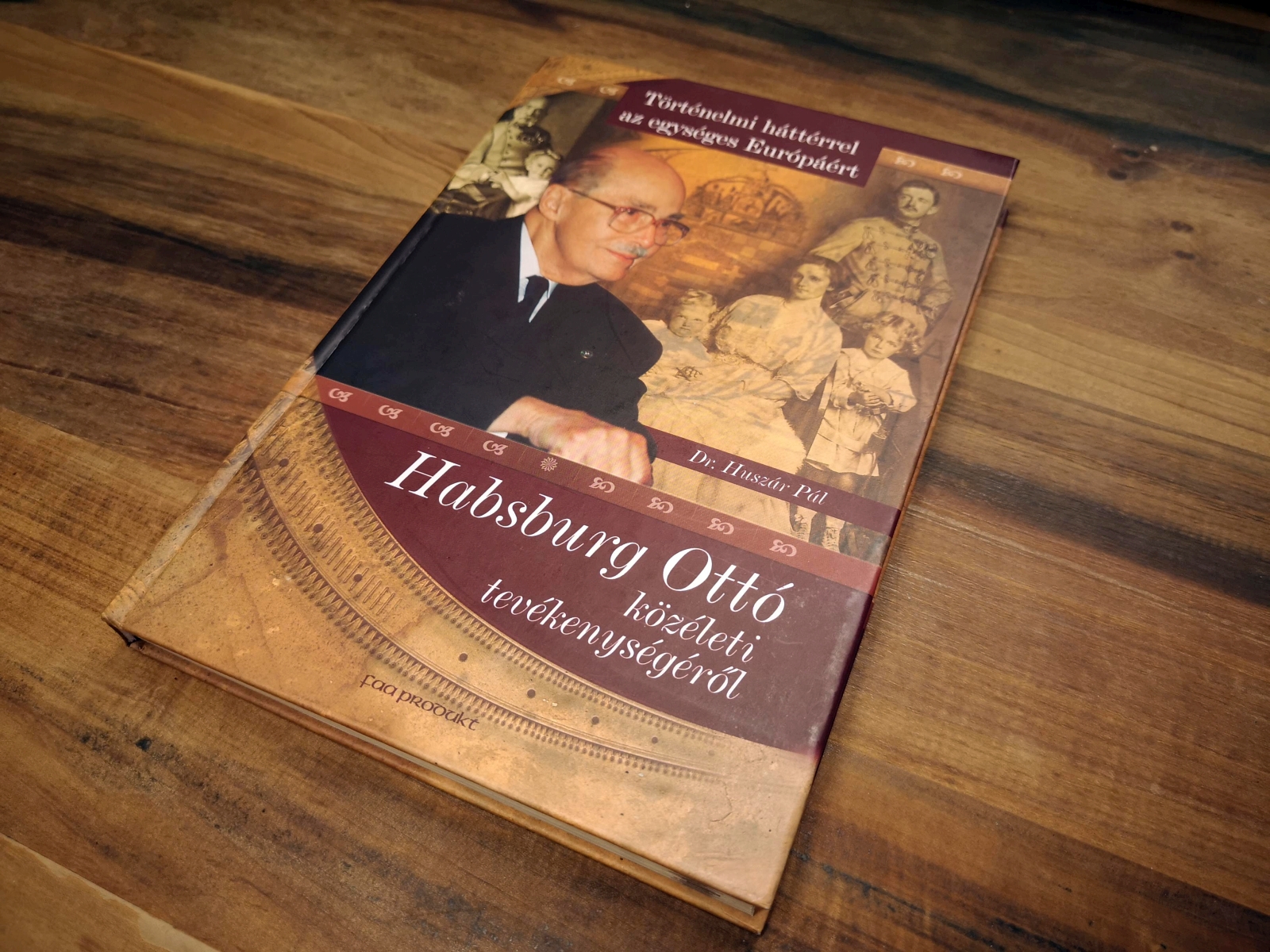

Pál Huszár had presented to the Archduke one of the first drafts of his volume on Otto von Habsburg’s public engagement almost a year before the above words were written. In the spring of 2003, at the invitation of Attila Kálmán, renowned Headmaster of the Reformed College of Pápa, the Archduke visited the Transdanubian town. The address of Otto von Habsburg in the densely packed Reformed Church, which the author of these lines also witnessed as a first-year high school student, was a touching moment of reconciliation. For it was the recatholisational ambitions of the former Crown Prince’s ancestors that forced the College to flee to the nearby Adásztevel and operate there for several decades in the middle of the 18th century, while prior to this, many of the town’s leading figures of the Reformed Church had been condemned to become galley slaves. At the same time, the event was a striking example of how the last heir to the Hungarian throne, then aged 91, was particularly dedicated to the cause of youth, education, and the nation’s and continent’s future.

Bence Kocsev

The Protestant churches in Hungary created the office of the Lay President, as we Lutherans call it, and, under the Reformed name, the Superintendent, to enable the vast Protestant community to assert its interests against the Catholic Habsburg Empire after the arduous period of the Counter-Reformation. The lay leaders, elected by the people of the church, i.e. with democratic legitimacy and mostly of wealthy, noble origin, were easier for the Court to find a voice with than with the clergy, and their secular, public affairs proficiency enabled the churches to advance their cause better. The parity system of the leadership of the Protestant churches also had a theological message: it brought into institutional form Martin Luther’s view of the universal priesthood, that is, serving the cause of Jesus Christ, was not bound to the priestly vocation, even if theological knowledge was still indispensable.

Until the Communist takeover, the Superintendent and Lay President positions were filled by representatives of the aristocracy of the Reformed and Lutheran faiths. During the dictatorship, the loyal supporters of the authorities and artists and intellectuals whose popularity could help the cause of the churches succeeded one another with varying dynamics.

Even after the regime change, it was mostly the latter who undertook and continue to undertake this service, seeking to support spiritual leaders at different levels of church government—from congregations, dioceses and parishes to the national stage.

Pál Huszár was a great example of a devoted churchman who was well-versed in the world’s ways. We met many times at conferences, protocol and church services, where we had the opportunity to interact as private people. In Hungary, although there is an apparent Reformed majority in the government, the Catholic dominance leads to a more clerical mentality, which in many cases cannot discern the meaning of secular leadership. Uncle Pali remarked on the strangeness of such situations with excellent humour. Likewise, it was exciting and amusing to converse with him when it was revealed that I work as director of the Otto von Habsburg Foundation while he was a staunch supporter of the last Hungarian heir to the throne and European politician; he had even written a book on his public career. This is how he came to be a guest at our events, where we always concluded that if, centuries earlier, the members of the Habsburg dynasty had been as generous and tolerant as Otto, our church offices might have never existed.

Pál Huszár’s deep faith, poise, elegance, and eloquence were exemplary even outside the Reformed Church community. May the Lord bless his memory!

Gergely Prőhle