Former Federal Chancellor Wolfgang Schüssel greeted the participants via a video message. The leading Austrian politician and former Minister of Economic Affairs began by warning against being an expert in a field with no other interest, contrasting it with the examples of Hayek and representatives of the Austrian school of economics. For a generation raised in the rich cultural tradition of the Monarchy, it was natural to pursue studies in sociology, philosophy, law, and the natural sciences, and after emigrating in 1938, they sought to transfer this outlook to the intellectual life of their chosen homeland. Their successors today must consider climate change, environmental sustainability, and numerous other factors when thinking about the market economy. According to Schüssel, who is also a member of the board of trustees of the Friedrich August von Hayek Foundation, the lesson to be learned from the liberal school of economics is that individual responsibility is paramount: it is bad policy for a government to accustom its citizens to always expecting help from the state.

“The creation of the liberal democratic political and social order in the second half of the 20th century was the greatest political achievement in modern times”, began Professor Otto Hieronymi. This achievement is now facing serious threats: from outside, by the authoritarian regimes of Putin’s Russia and communist China, and from within the Western community by Trump-style populism, protectionism, and nationalism.

Wilhelm Röpke was Hieronymi’s teacher, mentor, and thesis advisor during his studies in Geneva, and his influence left a lasting mark on the Hungarian scholar’s entire career. As he emphasized, the fundamental principles of liberalism as represented by Röpke were much more balanced than those those espoused by Mises and Hayek – and the social market economy established in West Germany (Erhard’s Wohlstand für Alle!) probably owed its rapid success and widespread influence to this.

Placed in historical perspective, it is understandable that the government that came to power after the first free elections following the change of regime returned to the principles of Röpke, and that Hieronymi, advisor to József Antall, played a prominent role in this decision. The scholar expressed his belief that the social market economy, in its updated, more flexible form championed by Ludwig Erhard, Wilhelm Röpke, and Müller Armack, would be able to find answers to the challenges of the past three decades, while he classified Mises as belonging to the more orthodox school of market economics. Nevertheless, Wilhelm Röpke, Ludwig Erhard, József Antall, and Ludwig von Mises all deserve their place among the intellectual and moral giants of our time, Hieronymi concluded. (The full text can be read HERE.)

Prince Michael von Liechtenstein, President of the European Center of the Austrian Economics Foundation in Vaduz, outlined general principles regarding today’s financial policy. What remains unchanged across all systems is common sense, which often views the irrational spending and misguided inflation policies of individual governments with incomprehension (because rising inflation is always the result of bad policy). And although it is clear that the European Central Bank is a policy-driven organization, efforts must be made to ensure that national banks always retain their independence and room for maneuver.

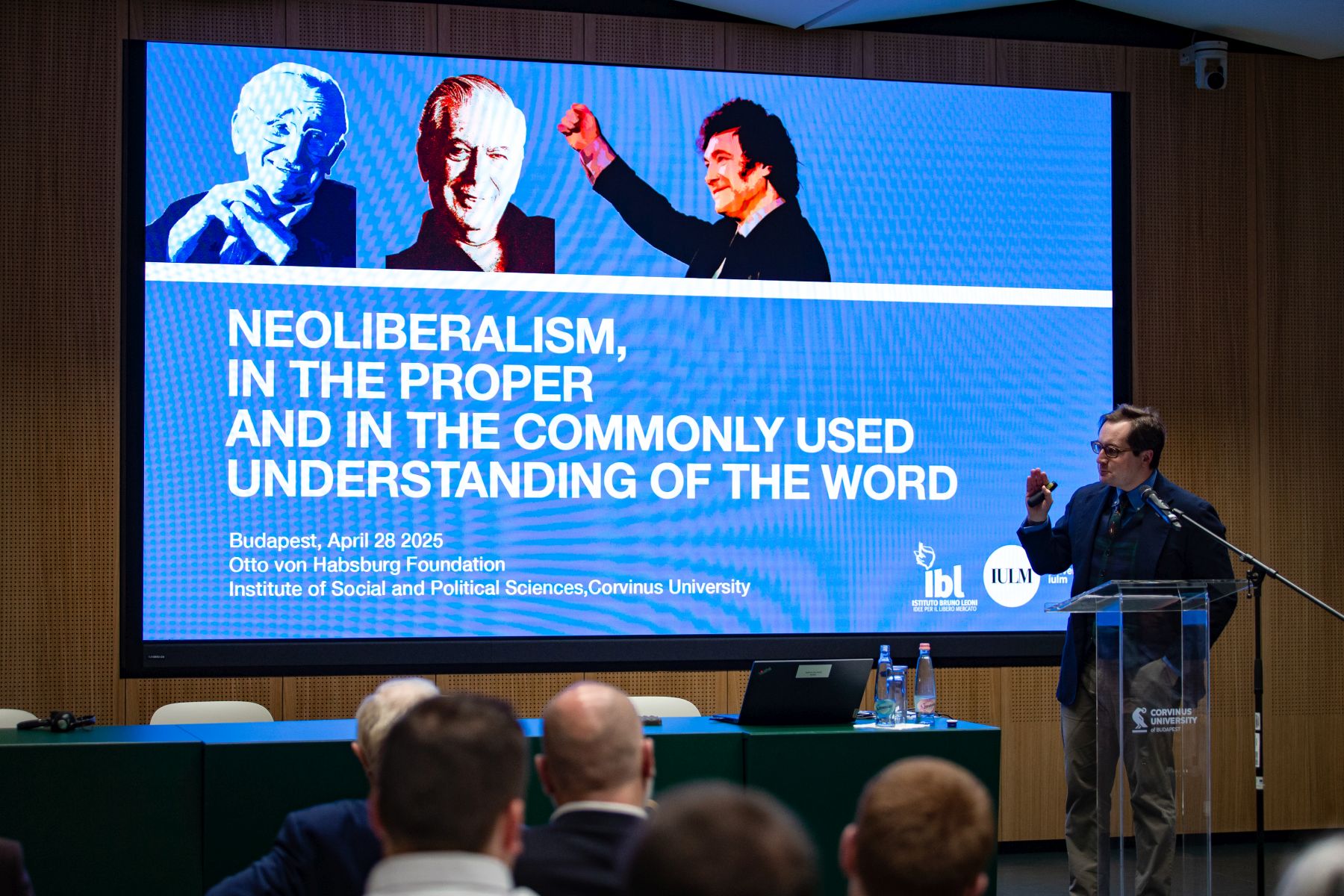

The concept of “neoliberalism” can be traced back to the 1938 Walter Lippmann conference, where it was introduced into professional terminology at the suggestion of French philosopher Louis Rougier to distinguish the new representatives of the movement and their ideas from classical liberalism – as we learned from Alberto Mingardi‘s lecture. Quoting Luigi Einaudi, the Italian professor warned that this description could apply to every generation of economists, as to a certain extent, each redefines the concept of liberalism. The Director of the Bruno Leoni Institute argued that although the term is now usually associated with negative connotations in academic discourse and public debate, it should be recognized that liberalism is responsible for the rise in GDP in developed countries and the global reduction of poverty.

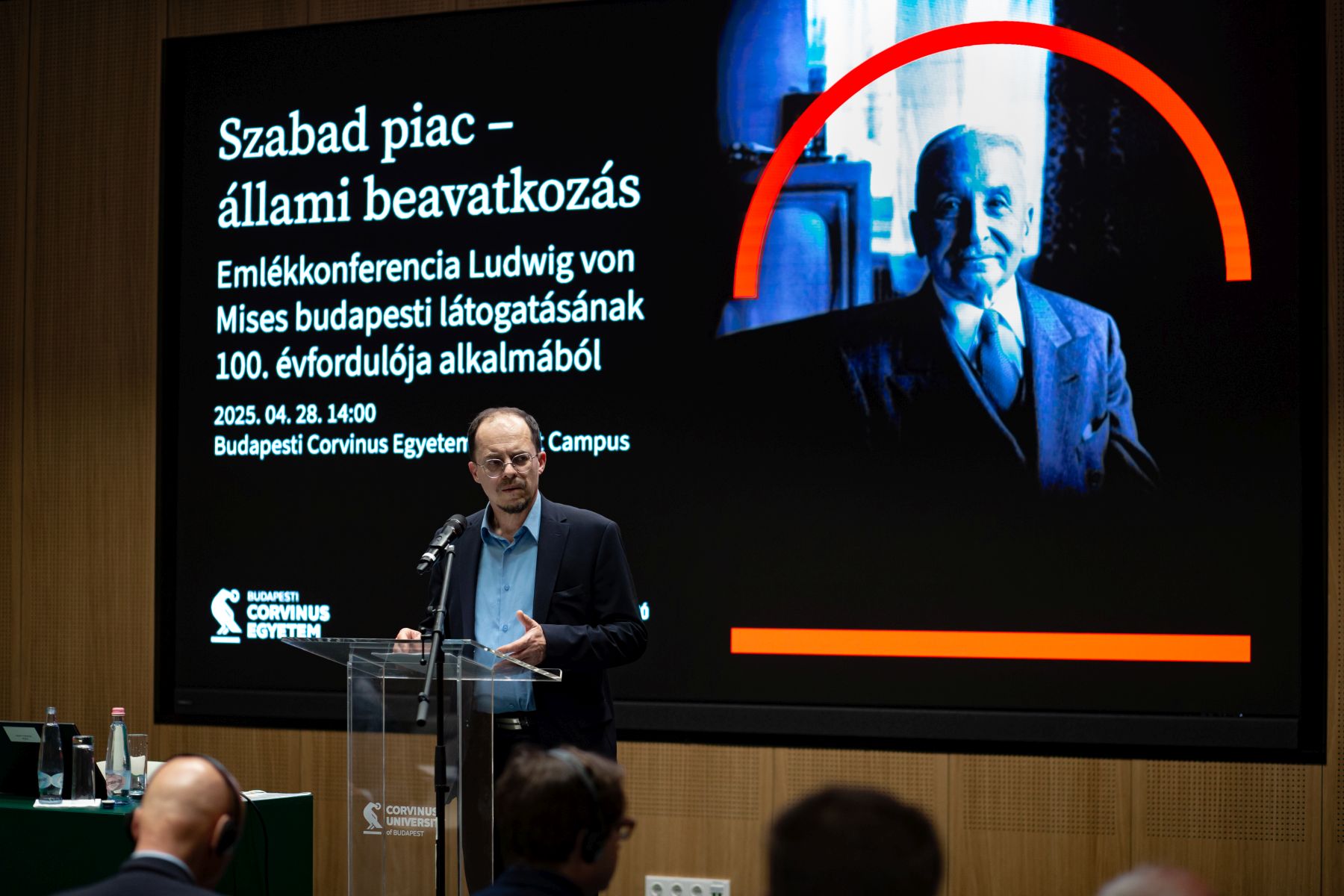

In the historical section of the conference, Gergely Kőhegyi sought to outline the different periods of the Austrian school of economics. Considered a synthesis of the Lausanne and Cambridge approaches, this school of thought can be traced back to Carl Menger and has produced four generations of dozens of outstanding scholars, who often achieved new results through fruitful debates with one another. Kőhegyi, professor at Corvinus University of Budapest, demonstrated their influence among Hungarian academics in the work of Farkas Heller, Ákos Navratil, Ede Theiss, János Kornai, and András Bródy.

Levente Nyitrai, diplomat, spoke about Friedrich August von Hayek’s work at the London School of Economics, where the passionate academic battle between the scholar, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974, and John Maynard Keynes, which lasted for many years and was conducted both in person and in studies and letters, is still remembered today. The conservative turn of the late 1970s then brought Hayek gratification, as Margaret Thatcher’s government regarded his work The Constitution of Liberty as the bible of its economic policy.

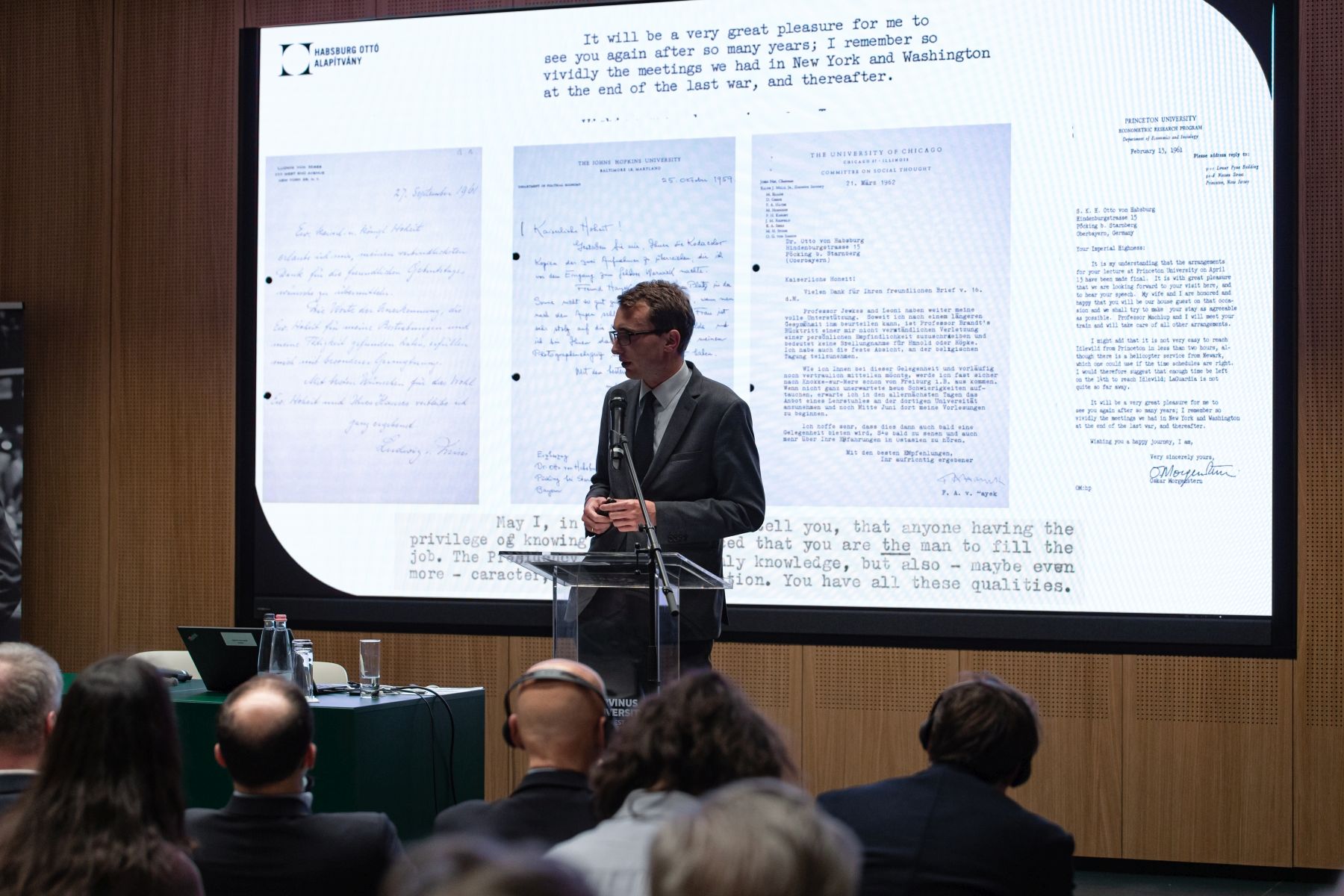

The Director of our Foundation presented Ludwig von Mises’ concept of peace. The renowned expert in his homeland was forced in 1940, at the age of nearly 60, to start a new life and academic career in a country with a language he was unfamiliar with. However, as he began to settle in, he became increasingly concerned about the post-war future of Central Europe. He envisioned a system in which the parties would realize that armed conflict was not economically viable and which would remain functional even in the event of a resurgence of extreme nationalism. Under the organizational framework proposed by Mises, everyone in the Eastern Democratic Union would have been free to choose their place of residence; only private schools would have been allowed to operate (eliminating state intervention); the decisions of the 600-member parliament would not have been restricted by the powers of individual member states, but he considered the preservation of national identities and the characteristics of each country to be of key importance. Although the author himself was aware of the utopian nature of his plan, in 1941 it still represented his attachment to Europe, which, however, gradually dissolved in parallel with his integration into American society. Otto von Habsburg later incorporated many elements of von Mises’ ideas into his own concept of Europe, as Gergely Prőhle pointed out.

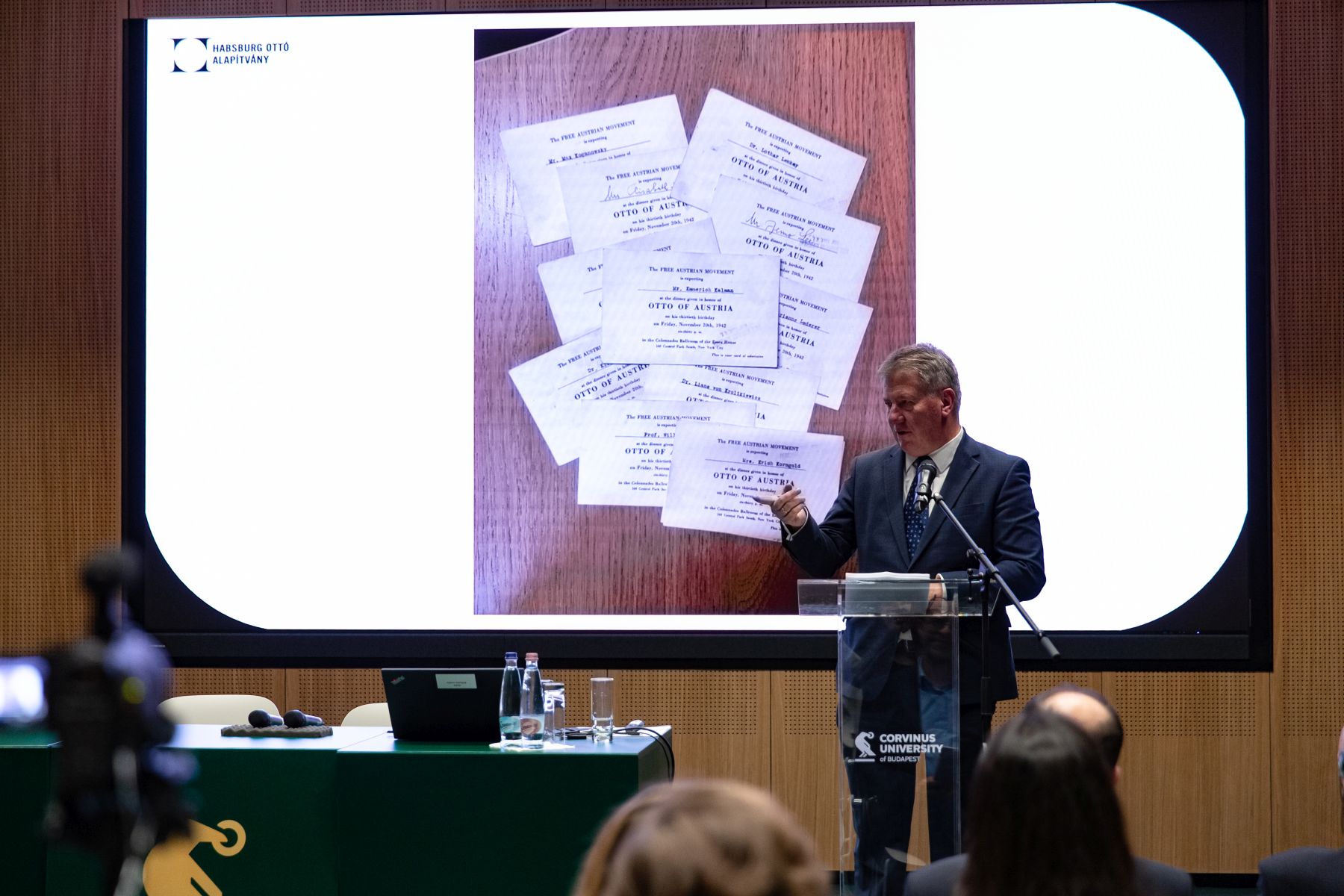

Bence Kocsev, drawing on documents in our Foundation’s archives, presented Otto von Habsburg’s relationship with the leading figures of the later generation of the Austrian school of economics. He discussed our namesake’s role in the Mont Pelerin Society, which was shaped in part by these thinkers, and highlighted how the values represented by the organization shaped his agenda in the European Parliament. He also emphasized that for the former heir to the throne, conservative political thinking and neoliberal economic ideas were not only compatible, but often reinforced each other.

The participants of the panel discussion held at the end of the conference were invited to discuss the topic “Free market and regulation: theory and practice during regime change.” Péter Ákos Bod, Minister of Industry and Trade in the Antall government and later President of the Hungarian National Bank, László Urbán, university professor and former Member of the National Assembly, and Gyula Pleschinger, former Member of the Monetary Council of the Hungarian National Bank, assessed the processes that have taken place in the Hungarian economy over the past 35 years, moderated by Enikő Győri, Member of the European Parliament.

Their opinions reminded the audience of the painful experiences of the regime change in many respects: the initial years of the transition to a market economy, which were fraught with contradictions from a social, economic and political point of view; the manifestation of civil will in the taxi blockade (autumn 1990); the corrective measures of the Bokros package (1995); the unspoken but necessary and successfully implemented further adjustments of the first Orbán government (1998); and the effects of the successive global economic crises since the end of the 2000s. As agreed, the individual topics are so complex that they would require a more in-depth analysis if addressed separately. The same applies to the accurate description of the current situation and the assessment of the tasks for the near future, the most pressing question being: how, alongside the phenomena we are experiencing today – migration, war, climate crisis, a Europe left to its own devices – will we preserve peace on our continent and the economic and social system built on neoliberal principles?

Photos: Zoltán Szabó