“What matters is not what we say about ourselves, but what can be understood from what we have lived through.”

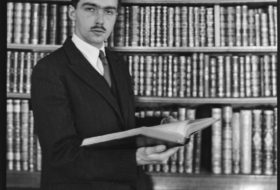

Otto von Habsburg

An Unwritten Memoir

Throughout his life, Otto von Habsburg consistently refrained from keeping a diary or writing memoirs. As he himself explained, he was always more interested in the future than in the past. This deliberate decision lends particular significance to the conversations—captured on camera—in which he repeatedly returned to the defining events of his life.

From the late 1970s onwards, Péter Bokor and Gábor Hanák conducted lengthy, unscripted interviews with Otto von Habsburg over several decades. These encounters took place at his residence in Pöcking, Bavaria, as well as in Budapest, at the National Széchényi Library, in Pannonhalma, Strasbourg, and Gödöllő. They were not structured question-and-answer sessions prepared in advance, but free-flowing discussions in which a current event—a referendum, a European summit, or a personal recollection—naturally opened onto broader historical perspectives. Thanks to the creators’ cinematic and editorial sensibilities, the television series In Place of a Diary, the documentary film By the Will of God, and the volume A Year with Otto von Habsburg can all be seen as different impressions of the same continuous, overarching conversation.

Historical Reflection with Humour and Self-Irony

The value of this film material also lies in the fact that Otto von Habsburg appears here not primarily as a historical figure, but as a reflective and analytical thinker. He speaks about the legacy of the Habsburg Monarchy, the dangers of nationalism, and the meaning of European integration, while with equal ease recalling childhood memories, former teachers, or explaining why he considered it essential to make good use of every minute of his time.

One particularly distinctive feature of these conversations is Otto von Habsburg’s characteristic tone, often marked by irony. Alongside serious historical analysis, unexpected and deeply human moments regularly emerge. He recounts, for instance, how he burned his notebooks at the end of each year—out of a healthy caution towards the Gestapo and later other police authorities—or why he considered Hitler’s Mein Kampf particularly dangerous because it was “too poorly written for anyone to read”.

At another occasion, he reminisces about a dinner in Debrecen spent with Roma musicians, where the Kossuth-nóta (a Hungarian patriotic song) and the Gott erhalte anthem could coexist without difficulty, because—as he emphasised—“history is not black and white, but made up of shades of grey”.

A Researchable Legacy

The complete interview series—including audio and video recordings, transcripts, and related documentation—was transferred to our Foundation over six years in six phases from the Archive of the Magyar Mozgóképkincs Megismertetéséért Alapítvány (Promotion of Hungarian Moving Image Heritage Foundation). Altogether, the material comprises more than 133 hours of audiovisual recordings produced between 1977 and 2005, documenting nearly three decades of reflection, intellectual engagement, and historical experience.

Following archival processing, the material will become accessible for research. Selected excerpts, however, are already available online: curated video clips can be viewed on the Otto von Habsburg Foundation’s YouTube channel. In the future, the Foundation plans to publish further interview excerpts, gradually making this remarkable body of audiovisual material accessible to a broader public.