The Yalta Conference took place in Crimea 80 years ago, from 4 to 11 February 1945. The international meeting, held in the Livadia Palace, built by Tsar Alexander II and rebuilt under his successor Nicholas II, has become a historic event. It brought together the leaders of the three great powers allied against Nazi Germany – Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill and Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin – and their delegations of several hundred people. After eight rounds of negotiations, the issues that shaped the post-World War II world order were decided here.

At the time of the conference, the cannons were still thundering in Budapest, the last bloody battles of the siege of the Hungarian capital were still being fought. Further north, Soviet troops crossing the Polish plain under Marshal Georgy K. Zhukov had reached as far as the Oder River, 40 km from Berlin, four days before the conference began. At the same time, Marshal Ivan S. Konev advanced towards the Neisse River. In the north-west, US troops tried to push forward by bombing Münster and Osnabrück, the sites of the negotiations preparing the Peace of Westphalia, concluding the Thirty Years’ War. The Germans were forced out of French territory around Colmar. In the north of Italy, the fighting was in the Bologna area. In the Far East, the American military leadership – according to Otto von Habsburg – at the time was pretty much certain that Tokyo was already mortally wounded and would be willing to make peace. He notes, however, that Roosevelt and his political advisers did not quite see it that way, and that the British in particular were concerned about Japan’s fierce resistance.[1]

Otto von Habsburg arrived back in Europe on 2 November 1944 from the United States, where he had lived as a refugee for four years. He stayed in Lisbon until the end of January 1945, when he left for France.[2] He was in Paris at the time of the conference. He made himself at home in the Hotel Cayre, where he ran a sort of anti-Nazi headquarters until 1940. In those days he was extremely concerned about the Soviet military advance and the emerging geopolitical situation. On 19 February 1945, he wrote to President Roosevelt raising the possibility of the early return of ‘reliable’ Austrian prisoners of war fighting on the German side and their deployment behind enemy lines, in order to reduce the risk of the country falling into Moscow’s sphere of interest after the war.[3] Otto von Habsburg’s goal was to save Austria from Soviet influence. He feared that the Red Army would not voluntarily leave the territories it had liberated – and occupied – after the final collapse of the German Reich.

Otto von Habsburg and his brother Felix in the United States during World War II

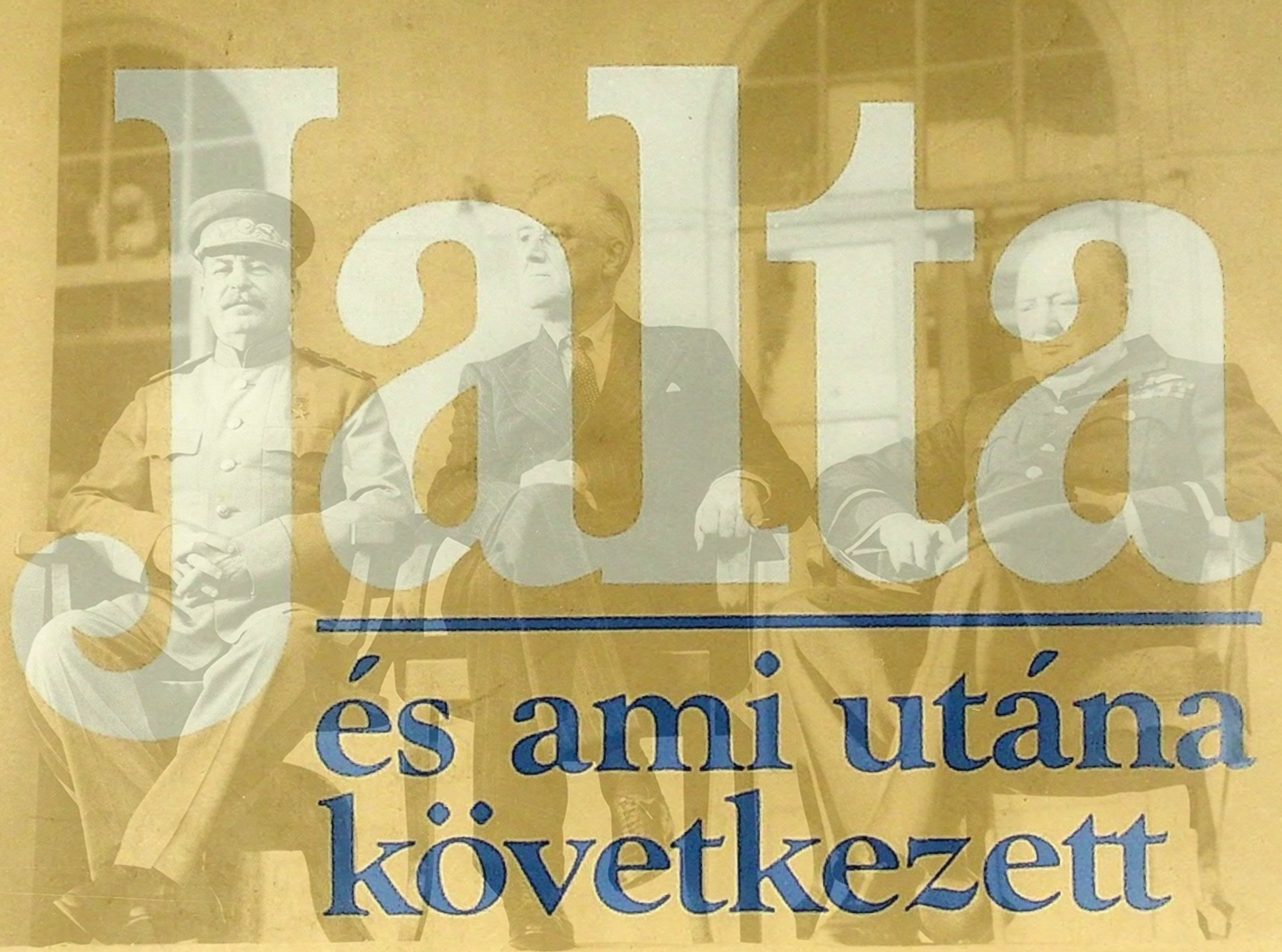

In February 1945, as usual, Otto von Habsburg tried to gather as much information as possible about the international situation and the events in Crimea itself, in order to assess events correctly. To this end, in addition to radio broadcasts and the press, he also used his contacts with Anglo-Saxon and other Western diplomats, journalists and politicians. He later regularly commented on Yalta, analysing its impact in numerous articles and lectures; in 1979, he chose the title “Yalta” for his book, which was one of the first to be published in Hungarian.[4]

Otto von Habsburg regarded the conference in the Crimea 80 years ago as a decisive turning point in world politics, but he doubted from the very beginning whether its results would stand the test of time. He considered the attitude of the negotiating powers to be mistaken. In the former Crown Prince’s view, the Yalta agreement was based on unnatural foundations and defied historical logic, leading immediately to tensions. Otto von Habsburg believed that all subsequent Cold War confrontations could be traced back to this conference. The fundamental problem, in his view, was that the great power negotiations of early February 1945 took place at a moment when the strategic – and therefore political – conditions were in favour of the Soviets and the Americans were in the grip of their illusions about Moscow.

In his analyses, Otto von Habsburg stressed that the German offensive in the Ardennes led by Field Marshal Gern von Rundstedt between 16 and 26 December 1944 had set back the Anglo-Saxon advance, and thus essentially had created a favourable military situation for the Soviets. According to the former heir to the throne, the American general staff and politicians took decisions mostly without taking into account the advice of Supreme Commander Eisenhower. On the basis of information gathered later, he saw the main culprit as General George C. Marshall, who, relying on data from General William J. Donovan’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS), had believed that the Third Reich still had retained considerable reserves and thus he had been cautious in making a military advance against Germany in the West. Eisenhower’s suggestion that the US delegation in Yalta should not approve definitive demarcation lines was not heard either – Otto von Habsburg stressed.[5]

The former Crown Prince also saw the very poor state of health of President Roosevelt as a negative factor. He had spoken to him personally in September 1944, a few months before the Yalta Conference, and had already sensed the severity of the illness of the American politician. According to Otto von Habsburg, this was all the more problematic because it was during the conference that Roosevelt realised that his permissive policy towards Stalin had been misguided, but he was in no physical condition to confront the Communist dictator. The US President reassured himself that the United States would end the war with such economic superiority that the Soviet Union would be forced to make concessions regarding the borders imposed at the Yalta Conference. Otto von Habsburg was also informed by the American diplomats present in Crimea that it had become clear very quickly that the Russians had been aware of everything that the Anglo-Saxons had discussed in private, citing confidential meetings to the letter.[6] The former heir to the throne regarded the role of undercover agents such as Alger Hiss[7] and Harry Dexter White[8] as crucial to the outcome of the Yalta conference, because he believed that these communist sympathisers in the US administration had provided the Kremlin with important information that the Soviets had been able to use in the negotiations.[9]

Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin in Yalta

Source: British Pathé

Nevertheless, the former heir to the throne emphasised that, surprising as it may sound, the main losing side at Yalta was Russia. In his opinion, the demands Stalin made at the conference were in fact inconsistent with historical logic, and his excessive territorial expansion in Europe and the tensions it had created demanded enormous energy from the Soviet Union. The successes in Yalta, in reality, diverted the Kremlin’s attention from the Far East, even though many analysts believe that Russia’s fate has always been decided in Asia. As early as the 1950s, Otto von Habsburg believed that the second half of the 20th century would be no exception to this. He saw the Kremlin’s great challenge in China. Otto von Habsburg was convinced from very early on that the Soviet Union could not be long-lived, because when it had perceived itself as the most powerful and influential, i.e. in Yalta, it had imposed decisions that had prepared the way for its own downfall.

According to Otto von Habsburg, Stalin’s agressiveness, which resulted in the decisions of the Yalta Conference, actually brought Europe not only senseless suffering but also great opportunity. The inhabitants of the Old Continent could not accept the partition that had been created in the Crimea in 1945, so that this coercion, paradoxically, endowed Europeans with considerable vigour and motivation. Not only had the actual common European construction begun, but it had also been partially completed, and a technological and industrial potential had been created which, a few decades later, surpassed that of the Soviet Union. But as the former heir to the throne puts it, the greatest blow to the Kremlin was that a united Europe “had an irresistible attraction for the hundreds of thousands of millions of Europeans who had been forced under Soviet rule since the Yalta agreements.”[10] With all this in mind, Otto von Habsburg constantly stressed from the very beginning that the existence of the Iron Curtain could not be accepted by the free world of the West.[11] He added that the Yalta decision had not been a necessity and that it had not been in Europe’s interest to insist on it. He warned later, after the fall of the Berlin Wall: “In today’s circumstances, delaying NATO enlargement simply because Russia opposes it, is a way of finalising Yalta. Although the so-called Yalta borders would be somewhat modified. But this does not change the main point, the damage and the dangers that this dictate has caused. Not to extend NATO today is to waste the achievements we owe to the heroism of the peoples of Central and Eastern Europe. It also involves accepting the conditions that Moscow is imposing as a basis for negotiation. By doing so, we are categorising the countries of Europe as first and second class, which will have fatal consequences.”[12]

Finally, Otto von Habsburg often compared the Congress of Vienna, which ended the Napoleonic Wars, with the Yalta Conference in his analyses. In 1965, twenty years after the negotiations in the Crimea, he wrote:

“At the Congress of Vienna, the understanding and acceptance of the fact that yesterday’s enemy was to be tomorrow’s ally was deeply rooted in the thought of the negotiators. However, in Yalta […] there was not the slightest trace of a sense of moral principle. Power politics alone was what mattered. Western representatives more than once joined Stalin’s brutal approach. Decisions were made solely on the basis of the prevailing, and in many cases only perceived, interests of the victorious powers, and even their own minor allies – Poland, for example – were treated little better than the defeated. At the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, however, an attempt was made above all to establish universally valid norms, norms which would be binding on victors and vanquished alike […] In Vienna, too, moral principles were violated and more than one decision was dictated by special, often illegitimate interests. Yet, unlike in Yalta, this was not the rule but the exception.[….] If a treaty is dictated by mere power politics, irrespective of any moral considerations, it necessarily has the effect of dismantling the state and the inter-state framework and of intruding profoundly into the life of the individual. The extermination of entire populations, the violation of human rights, is always a logical consequence of an international illusory order based solely and exclusively on law of force. […] In a historical hour, it is a moral duty to draw lessons from the past and to turn the experience of humanity into action. At such a time, we must not forget that only respect for and the realisation of human rights can bring true peace. In order to achieve peace based on the rights of the individual, the necessary means must be found and taken today…”[13]

Otto von Habsburg’s exhortations, the thoughts quoted above, 80 years after Yalta and 35 years after the fall of the Iron Curtain – in an era when a new world order is taking shape – not only serve as a reminder, but can certainly also offer guidance worth considering.

Gergely Fejérdy

[1] Habsburg, Otto: Damals begann unsere Zukunft. Wien – München, Herold, 1971, 115. (hereinafter referred to as: Damals begann)

[2] Baier, Stephan – Demmerle, Eva: Habsburg Ottó élete. Ford. Blaschtik Éva. Budapest, Európa, 2003, 186.

[3] https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1945v03/d382 (downloaded: 2025.01.31.)

[4] Habsburg Otto: Jalta és ami utána következett. Válogatott cikkek, tanulmányok. München, Griff, 1979.

[5] Damals begann, 114–115.

[6] Habsburg Ottó: Sztálin két történelmi tévedése. Új Európa, 1971, 1, 7–11.

[7] To this day, it has not been proven whether Alger Hiss was in fact a Soviet spy in the US Department of State.

[8] It is a well known and undisputed fact that Harry Dexter White, one of the key figures in the creation of the Bretton Woods system, was a Communist Party member and informant for the Soviet Union in the 1940s.

[9] Damals begann, 137.

[10] Habsbourg, Otto de: Perspectives européennes dans la politique mondiale. In: Gaupp-Beghausen, Georg von: 20 années C.E.D.I. Madrid, Nacional, 1971, 643.

[11] Habsbourg, Otto de: Vers une Europe nouvelle. In: 20 années C.E.D.I., 66.

[12] Habsburg Ottó: Az atlanti szervezet bővítése. Magyar Hírlap, 1997. május 10., 3.

[13] Habsburg Ottó: Az igazi béke alapja. Új Európa, 1965, 7/8, 5–6.