Otto von Habsburg, Robert and Adelheid in Reichenau (1917)

The book A mi királyi családunk (Our Royal Family) by Károly Huszár, a royalist politician and later Prime Minister, was published in 1918.[1] In the preface, the author defined the purpose of his work as follows: “It aims to be a brief summary of all that should be known about our royal family by every educated Hungarian”.[2] A whole chapter is devoted to the children of the royal family, in which, among other things, the orderly character of Otto is emphasised. In addition, we can read about the then 6-year-old prince’s favourite game, playing with trains, where he always took on the role of the engine driver, befitting an heir to the throne.[3]

Some anecdotes about the young Otto von Habsburg have been preserved in newspapers. In the journal Budapest, published in the summer of 1918 under the title The Little Crown Prince, one can read – with a somewhat didactic overtone – about the deeds of the kind-hearted little boy who gives his shoes to the poor barefoot child, moreover, including his governess’s battle-fallen brothers in his evening prayers.[4]

The heir to the throne appears in several of the juvenile novels of Mária Blaskó. In her book, A kiskirály (The Little King), published in 1924, the youth of the time could read stories about the life of the young Otto von Habsburg.[5] The preface to the tale of Két királyfi (Two Princes) is a letter containing Otto’s message: “With royal affection, he bids every child of his beloved country to follow his example; to study and work diligently and joyfully, so that these children may become the hardworking hands which are destined to raise the future Hungary to prosperity, glory and contentment.”[6] The Crown Prince’s lines from Lequeitio were sent to the writer, Mária Blaskó, by Countess Margaret Wenckheim, who, along with her husband Count Joseph Károlyi, had aided the royal family in Madeira and during their exile in Spain.[7]

The work of Ferenc Móra, a classic of Hungarian youth literature, is also linked to Otto von Habsburg in several ways. According to a rapturous article in one of Hungary’s oldest newspapers, Délmagyarország, published in November 1927, Móra was the best-known Hungarian writer in the world.[8]

Deputy Secretary of State Elemér Czakó, an advisor to the Ministry of Religion and Public Education and General Director of the Royal Hungarian University Press, commented to the same newspaper that the royal children, including Otto, learnt Hungarian from the series of elementary reading books, Betűország (Country of Letters), edited by Ferenc Móra and Géza Voinich. Furthermore, the royal household also benefited from the texts, as they provided a better understanding not only of the Hungarian language but also of the Hungarian people.

Ferenc Móra’s novel, Szél ángyó jót akart (Aunt Szél meant well), was published on 25 April 1926 in the columns of the journal Világ and later in the 1927 volume Véreim (My brethren).[9] In it, the writer portrayed the character of his host in Szatymaz.[10] According to the plot, the poor couple wants to send the widowed Queen Zita a letter requesting that they take one of the orphans to live with them. They wish to raise the eldest, Otto, because, as the husband says: “He’s the most affluent and the fastest to become a man. Even we’d live to see that.” They intend to give him their name, their farm, their vineyards, their land, and all their possessions. However, according to Móra, there is a law that the royals shall only pasture golden lambs, thereby thwarting the grand plan. Nevertheless, the story is an intriguing example of the royalism of the peasantry.

Ezek az évek 1914–1933 (These Years 1914-1933) was the title of the collection of Móra’s editorials penned during the relevant interval. The writer reflects on the child Otto von Habsburg in his 1927 essay Szegény kis népcsászár! (Poor little People’s Emperor!).[11] He regards the orphaned heir to the throne, the child exiled in Spain, with trepidation and compassion. Contemplating his future, he expresses the hope that if Otto von Habsburg does not succeed as monarch, he will turn out to be a happy and content man, brought up to earn his living by his own labour.

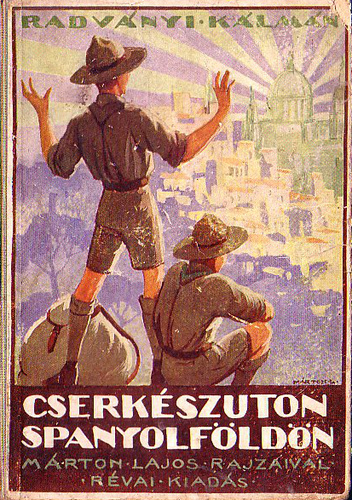

Scoutmaster Kálmán Radványi was a popular juvenile writer in the interwar period. One of the settings of his multi-published book Cserkészuton spanyol földön (Scouting Trip on Spanish Soil) is Lequitito, a Basque fishing village and the refuge of the royal family. The Hungarian Scout Association’s newspaper, the Magyar Cserkész (The Hungarian Scout) of 1 December 1930, described the release of the novel as one of the highlights of the Christmas book market.[12] The source of the work was the event in 1929 that took place after the conclusion of the 3rd World Scout Jamboree in England, when the commander-in-chief of the Hungarian troops, Dr Kasszián Mattyasovszky, a Benedictine monk and schoolmaster from Esztergom, left the squad with a couple of boys to attend the Spanish National Scout Camp (Exploradores de España) in Barcelona. During their trip, they also visited Otto von Habsburg and his family.[13] According to the Magyar Cserkész, “a special sensation is the part of the book in which the Hungarian scouts’ encounter and interaction with the royal family is described”. The chapter “Melegszemű édesanya, nyolc árva” (Warm-eyed Mother, Eight Orphans) describes the meeting between the boy scouts and the royal family. The monthly magazine of the Regnum Marianum Catholic youth community, Zászlónk (Our Flag), of 15 October 1929, also published a picture of the park of the castle in Lequeitio, where Otto is seen with his brothers and the Benedictine headmaster, accompanied by the boy scouts.[14] The picture also includes a drawing made on 28 August 1929 in the same place, in the chapel of the Royal Palace. According to the description, Otto celebrated the Mass.

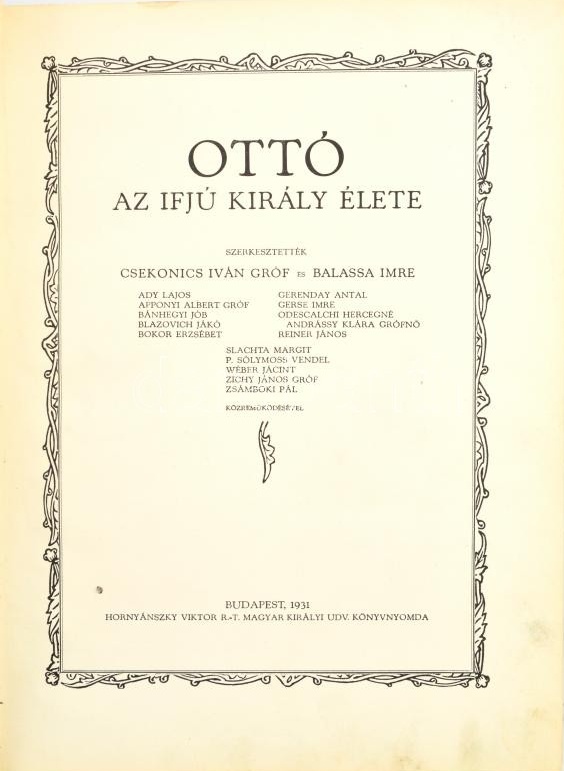

In 1931, after the heir to the throne came of age, the collection Ottó. Az ifjú király élete (Otto. The Life of the Young King) was published in Budapest, edited by Count Iván Csekonics and Imre Balassa. The richly illustrated volume follows the life of Otto von Habsburg up to the age of 18. The entertaining chapters, written by Imre Balassa, are complemented by reflections on Otto von Habsburg from Pál Zsámboki, Jákó Blazovich, Jób Bánhegyi, Vendel P. Solymos, Erzsébet Bokor, who were all involved in the upbringing and education of the royal children, as well as from Lajos Ady, who was at his high school graduation.

The works mentioned were written in the twilight of the Monarchy or during the period of the kingless kingdom and are imbued with loyalty to the royal family and compassion for the exiled. We have yet to determine precisely when Otto von Habsburg read these works, but they are certainly mentioned in several instances in his Hungarian-related correspondence from 1988-2011.[15] Thoughtful letter-writers drew Otto’s attention to these texts and even sent him extracts. Therefore, in these years at the latest, the protagonist himself could become acquainted with the stories about him.

Eszter Gaálné Barcs

[1] The volume can be found in the library of Otto von Habsburg and was given to him in 1991 by the Budapest representative of the Hungarian Heart Foundation.

[2] Károly Huszár: A mi királyi családunk (Our Royal Family), Budapest, Újságüzem Könyvkiadó és Nyomda Rt, 1918. 3.

[3] Ibid. 187.

[4] Budapest, 14 July 1918, 4-5.

[5] Analysis of the work by Anikó Nagyillés: A száműzött királyfi. Habsburg Ottó alakjának szimbolikus és narratív megformálásai. (The Exiled Crown Prince. The Symbolic and Narrative Formations of the Figure of Otto von Habsburg.) In. Gábor Barna (ed.): „A királyhűség jól bevált útján…” (The well-tried path of royal loyalty…). Szeged, MTA-SZTE, 2016, 457-471.

[6] Blaskó Mária. Két Királyfi (Two Princes), Budapest, Pallas, [1926]

[7] Count József Károlyi published his memoirs in 1922. Count József Károlyi: Madeirai emlékek (Memories of Madeira). Székesfehérvár, Fejér County Archives – József Károlyi Foundation, 1996. (A Fejér Megyei Levéltár Közleményei 20.)

[8] „Móra Ferenc a legelterjedtebb magyar író a világon” [sic] (Ferenc Móra is the most popular Hungarian writer in the world). Délmagyarország, 6 November 1927, 5.

[9] The narrative “Szél ángyó jót akart” (Aunt Szél meant well) is available here: https://mek.oszk.hu/00900/00974/html/08.htm (Date of download: 24.03.2023.)

[10] László Péter: Szél ángyó Báránya (The Lamb of Aunt Szél). Magyar Nemzet, 27 July 2009, 36.

[11] The essay can be read at: http://mek.niif.hu/05200/05283/05283.htm#24 (Date of download: 24. 03. 2023.)

[12] Magyar Cserkész, 1930, 23, V.

[13] Kasszián Mattyasovszky: Az angliai cserkészjamboree a mi szempontunkból (The English Scout Jamboree from our Point of View). Pannonhalmi Szemle, 1929, 1, 580-587.

[14] Zászlónk, 15 October 1929, 35.

[15] This collection of records has been processed, and the digitisation of the documents is in progress and is partly available digitally on our website.