The period of overseas emigration during the Second World War was a notable milestone in Otto von Habsburg’s burgeoning public career. The political and diplomatic efforts of the years in Washington were evidence of his sense of responsibility towards the successor states of the Monarchy and the future of the European continent, as well as the increasingly definite outlines of his later political views. However, the most adventurous aspect of the biographical narratives, which extend over the war years, does not lie in the description of the political and networking activities of the former Crown Prince but in the account of the perilous journey that Otto von Habsburg, hounded by the Third Reich, took from the castle of Steenockerzeel through France, Spain and Portugal to the United States in the spring of 1940. At the heart of these stories is the Portuguese diplomat Aristides de Sousa Mendes, who played a pivotal role in the success of the escape of the former Crown Prince and his family.

The Consul General—who saved the lives of countless refugees, including many of Jewish descent, by issuing Portuguese visas en masse against the explicit orders of the political leadership in Lisbon when France was invaded in 1940—remained unknown to his country and the broader international public for decades. His lifesaving work was not recognised until 1966 when the Yad Vashem Institute bestowed him the title of Righteous of the World. By contrast, his rehabilitation in his own country could only take place in 1988, nearly a decade and a half after the “Carnation Revolution”, the fall of the Portuguese authoritarian regime.

Otto von Habsburg understood that the Consul General’s act of Christian charity, which saved the lives of thousands of people, was not without lessons and that he, too, had a vital role to play in commemorating and perpetuating his heroic deeds. Maintaining his memory and passing on this slice of history and family legacy from one generation to the next has proved successful, as the daughter of the former Crown Prince, Michaela von Habsburg, spoke a few years ago about how Sousa Mendes was a crucial figure in the family legendarium. She explained that the diplomat was featured so frequently in her father’s reminiscences that it felt like the special guest sat at the dinner table with them in the evenings.

The Habsburg Family in America (1943)

Born in 1885 into a wealthy, devoutly religious family, Sousa Mendes’ commitment to public service and his multigenerational experience of active participation in political life contributed significantly to the future diplomat’s work. Following a law degree at the prestigious University of Coimbra, he joined the foreign service alongside his twin brother César, also a distinguished humanitarian, who served as ambassador to Warsaw during the Second World War. His diplomatic career fell on turbulent times in domestic politics, and the succession of rapid changes also substantially impacted foreign affairs. The final days of the Portuguese Monarchy saw Sousa Mendes abroad in his first posting, as did the events of the parliamentary democracy of 1910 and, a decade and a half later, the advent of authoritarian government under Salazar’s Estado Novo. At the zenith of an eventful career in the foreign service, he was appointed head of the Portuguese Mission in Bordeaux in 1938 after numerous overseas and European assignments. He was there when France was invaded in 1940, which radically transformed the hitherto predictable diplomatic routine.

Witnessing the desperate plight of the masses fleeing the advancing German army, the diplomat—against the express prohibition of his government—issued visas to Portugal in droves, thus playing a vital role in the escape of Otto von Habsburg and his family in 1940, who were accused of treason and persecuted by Nazi Germany. This valiant action made it clear that for him, the defence of the dignity of human life was not just an abstract legal norm but a fundamental duty stemming from his Christian faith and personal and professional socialisation. Regardless of their religious, ethnic, political or financial status, he endeavoured to help people in difficulty, including Salvador Dalí, who fled to France after the Spanish Civil War, and the writer Aladár Tamás, who had a distinguished diplomatic career in the 1950s and 1960s, many members of the French branch of the Rothschild family and many politicians, artists and scientists who later rose to prominence, as well as many ordinary people. The number of those rescued has subsequently been the subject of intense historical debate. Still, even without precise figures, it remains clear that the political, intellectual and cultural history of Europe and the United States owes a great deal to Sousa Mendes’ 1940 stand. For example, Dalí’s arrival in America played a crucial role in making New York one of the artistic centres of the post-war years, and it also enabled European émigré governments and critical figures in post-war reconstruction to leave the Old Continent on Portuguese visas.

However, the diplomat’s disobedience, which put the need to help those in a vulnerable situation above loyalty to the political leadership in Lisbon, was not without consequences: he was suspended in the early summer of 1940, and disciplinary proceedings were initiated against him. Although he was aware that the final verdict was not in the hands of the transient earthly power but in God’s, his period of persecution, which he bore with dignity, took its toll on his health. He died penniless, neglected and forgotten in the spring of 1954.

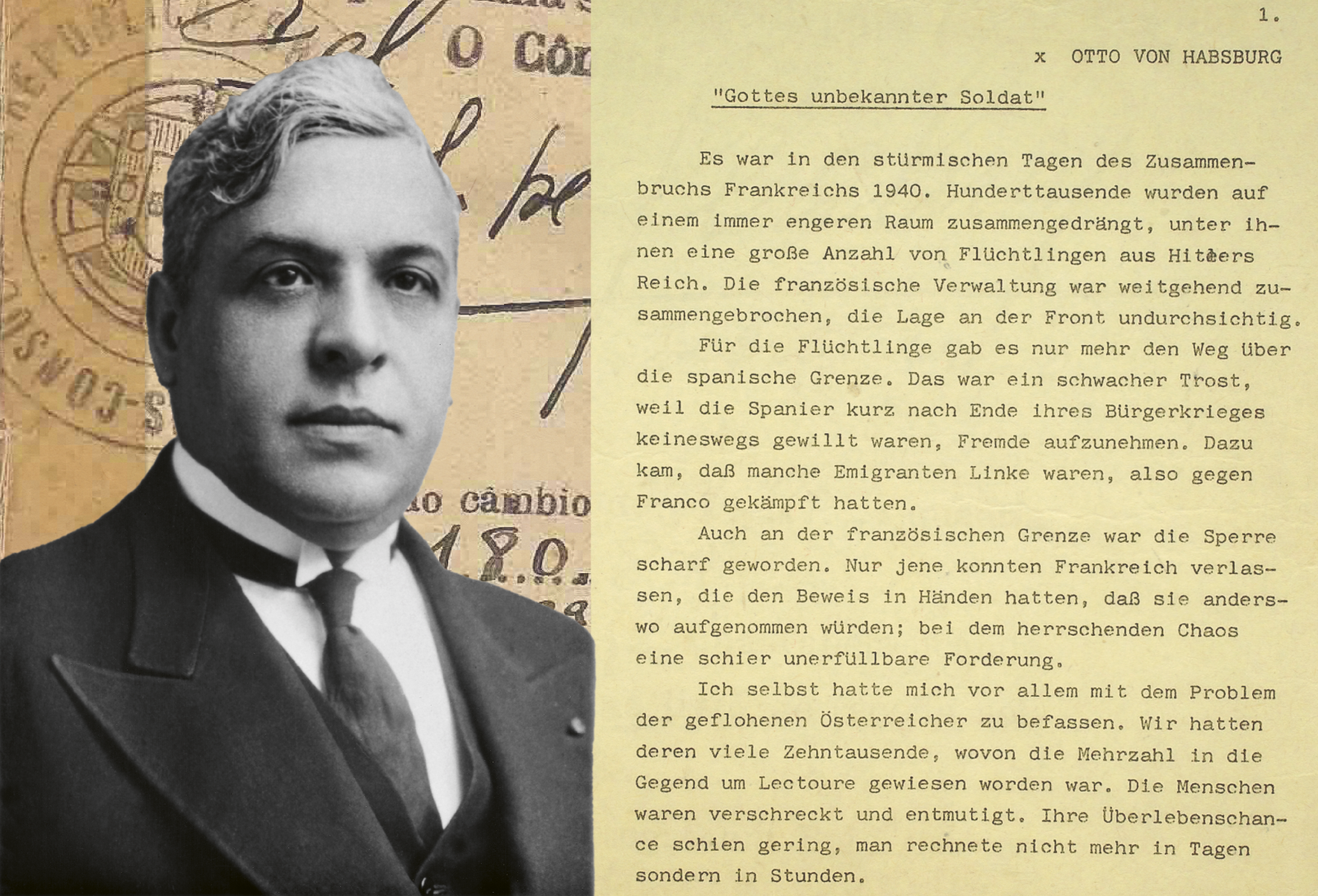

When Otto von Habsburg was approached to write about a life-changing encounter with a person in a multi-authored publication to be compiled for the 1987 Kirchentag, a traditional event of German evangelicalism, he decided on Sousa Mendes. On the 70th anniversary of the former diplomat’s death, we honour one of the forgotten heroes of wartime manslaughter with a translation of this essay. The original version of the text, the correspondence with the editors and the letters between Otto von Habsburg and Antonio de Moncada de Sousa Mendes, the grandson of the rescuer, are preserved in the Foundation’s archives. Since 2010, the Sousa Mendes Foundation, named after him, has been dedicated to the memory of the former Consul General, also known as the “Portuguese Wallenberg”.

HOAL I-4-a-Kéziratok, cikkek, disszertációk tanulmányok

Soldier Known but to God

It was 1940, in the tempestuous days of the collapse of France. Hundreds of thousands of people, including large numbers of refugees from Hitler’s empire, were forced into increasingly restricted spaces. The French public administration had mostly collapsed, and the situation on the front was murky.

The only option for the refugees was to cross the Spanish border. This proved a poor consolation because the Spanish, shortly after the end of the Civil War, were not willing to accept foreigners at all. In addition, some of the refugees were leftists who had fought against Franco.

Passing the French border was also tightened. The only people allowed to leave France were those who could prove that they would be accepted elsewhere, an almost unachievable demand in the chaos that prevailed.

I myself had to deal with the issue of Austrian refugees in the first place. There were tens of thousands of us, most of whom were sent to the area around Lectoure. The people were frightened and hopeless. Their chances of survival seemed slim; they were no longer counting in days but hours.

In this desperate situation, one man stepped into the breach: the Portuguese diplomat Dr de Sousa Mendes, head of his country’s Consulate General in Bordeaux. He had received strict instructions from his government not to grant visas.

Portugal was weak, fearful of Adolf Hitler’s inexorably advancing troops, and unwilling to incur the dictator’s wrath. Meanwhile, the Spaniards were willing to let through only those whose passports contained a destination. Dr de Sousa Mendes was a devout Christian and a soulful man. He, therefore, decided to defy the orders of his government. He granted Portuguese visas to all refugees without further examination.

I personally handed the passports of the refugees to Dr de Sousa Mendes, who provided those with Portuguese visas upon my request, and then the Spanish representative, Propper y Callejon, allowed passage through his country. The Portuguese consulate was kept open round the clock during these days. The Consul General himself worked non-stop for forty-eight hours. All the telegrams from Lisbon, with instruction reminders, ended up in the wastepaper basket. The efforts of Dr de Sousa Mendes saved the lives of more than 30,000 people. He did not ask whether they were Christians or Jews, Austrians, Germans or other Europeans. He was acting from a sense of Christian duty and humanity. When the task was completed, and the troops of the Third Reich arrived, Dr de Sousa Mendes was immediately discharged.

Since then, many have boasted about their actions—except for the Portuguese. Although his dismissal severely affected him, and he lived in extreme poverty, he rarely mentioned his heroic deeds. He wanted no earthly reward. He was content with having fulfilled his duty to God and humanity.

To this day, Dr de Sousa Mendes is almost universally forgotten, remembered by few. The most beautiful epitaph for him is expressed in the words of a man whose life he saved: “Thank God, there are no unknown soldiers before the eternal Judge.”

Annotation: HOAL I-2-b-Rainer Meier (the text was published in Telegramme aus Lissabon 68-70 In: J. Rainer Didszuweit u. Rainer Meier: Niemand ist allein. Begegnungen. [Neubuch] im. Auftr.d. Arbeitsstelle ’87. d. Evang. Kirche in Hessen u. Nassau für d. Kirchentag in Frankfurt

Eszter Barcs

Bence Kocsev