On 28 March, the two institutions dedicated an academic conference to the politician, historian and publicist. The opening lecture by Botond Kertész, Head of the Central Archives of the Lutheran Church in Hungary, illustrated the cultural phenomenon of the evangelisches Pfarrhaus with a series of examples. The model is Luther’s home, which for five hundred years has been a cultural topos of spiritual and intellectual growth among evangelicals, being an inspiring intellectual environment for many, from Friedrich Nietzsche and Hermann Hesse to Angela Merkel, from János Balassa to Gábor Sztehlo, from Ľudovít Štúr to Milan Hodža.

Pál Pritz’s general description of the period gave a vivid picture of the forces that had been at work in Hungary at the turn of the 20th century. Gratz had to remain true to his convictions during this turbulent period, while his personality was characterised throughout his life by a “visceral aversion to upheaval” and his political views by a supranationalist liberalism. His work was likewise put in a historical-ideological context by Péter Csunderlik. The professor of ELTE discussed the place and role of Gratz in the Society for Social Sciences (Társadalomtudományi Társaság) and the debates over principles within the editorial board of the journal Huszadik Század, which eventually led to the break-up of the board in 1906 and the secession of the conservative wing.

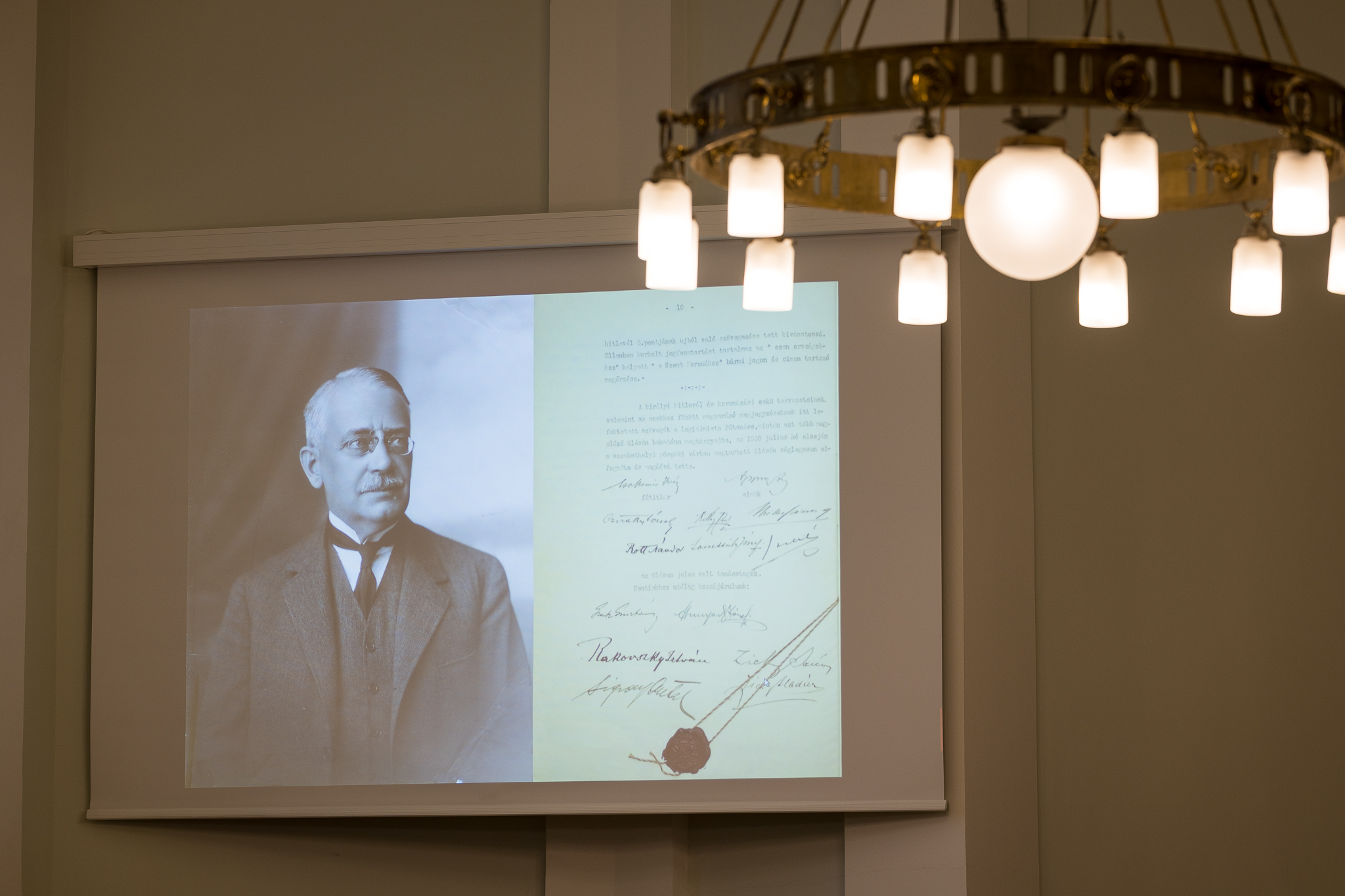

Róbert Fiziker used a rich apparatus of quotations to give the audience a sense of how contemporaries and posterity viewed the legitimists (rather ironically). Ignác Romsics, on the other hand, unpacked Gratz’s assessment of Hungary’s more recent history by examining the politician’s works as a historian. In his monumental overview entitled A dualizmus kora (The Age of Dualism), Gratz’s sympathy is clearly with Deák, as he believes that any change to the system of the dual monarchy – either federalistic or enabling an independent Hungarian nation-state – would have only hastened the disintegration of the state. Writing about 1918-1919 in his book A forradalmak kora (The Age of Revolutions), the biased approach of the historian is even more evident; he depicts only the leaders of the Soviet Republic in a darker light than Károlyi, and his style of portrayal often slips into the propagandistic register. Gratz’s political conviction shines through the lines of his book Magyarország a két világháború között (Hungary between the Two World Wars), published in print only at the turn of the millennium, creating, with his criticism of Horthy and Bethlen and his idealisation of King Charles IV, perhaps the most consistent and comprehensive legitimist historiographical narrative of the period.

For nearly a decade and a half (1924-1938), Gratz was the President of the Society for German Education in Hungary (Német Népművelődési Egyesület, Volksbildungsverein), and until 1933 he was Co-Director of the organisation with Jakab Bleyer. András Grósz‘s lecture helped to clarify the cornerstones of the two men’s differing approaches, namely Staatsgemeinschaft versusVolksgemeinschaft. Ferenc Eiler told the rest of the unfolding events: the minority in Hungary was not immune to the influence of the Third Reich on the German population of the region; from the struggle between the position of the legitimist politician and the stance of the radical new generation, the latter emerged victorious.

Lastly, Vince Paál evoked the personality of Adolf Gusztáv Gratz, a man of both modesty and ambition. His legendary diligence, combined with great accuracy, explains how Gratz was able to make a lasting impact in every field he had worked in – as a journalist, politician and historian. His acceptance by his contemporaries was undoubtedly due in part to his willingness to compromise in times of conflict. He was looked up to by his legitimist friend, Sándor Pethő, not only because of his deep knowledge of historical philosophy, but also because he considered Gratz a sincere advocate of the ancient Hungarian tradition, and at the same time a man who could incorporate modern, progressive ideas into his thinking.

Gergely Prőhle, Director of the Foundation and Lay President of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Hungary, thanked the National Media and Infocommunications Authority and personally President András Koltay: with their support, Luther Publishing House will soon release a Hungarian translation of Gusztáv Gratz’s memoirs, which until now have been available only in German.

Photos by Márton Magyari