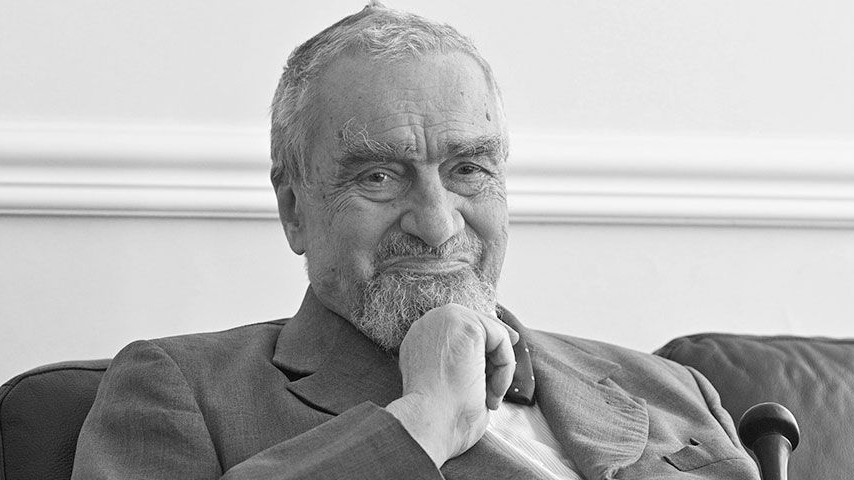

Karel Schwarzenberg was one of the last representatives of a generation that experienced the turmoil of the 20th century first-hand in (Central)Europe and whose political and public activities were largely determined by the conclusions drawn from it. He was born in 1937 as the second child of a princely family with roots in Central Franconia but deprived of its privileges after the dissolution of the Monarchy. A year later, his homeland was partitioned by the Munich Agreement, and his family was persecuted by the Nazis and subsequently by the emerging Communist regime. The coup d’état of February 1948 eventually led to the family’s forced emigration. From an early age, he became a prominent advocate of the Austrian People’s Party (Österreichische Volkspartei, ÖVP) but never assumed formal political office in Austria. In the 1960s, he established links with Czechoslovak dissidents and supported the developing opposition movement in the country and later the persecuted signatories of the Charter 77 initiative. His public work became increasingly visible at the turn of the 1970s and 1980s, when, as chairman of the International Helsinki Committee, he led the struggle for the realisation of the rights of freedom beyond the Iron Curtain enshrined in the Helsinki Final Act from his office in his Vienna apartment.

After the regime change, as head of the chancellery of Václav Havel, he was instrumental in overseeing the post-communist transition. The country’s leadership, which had little experience with official politics in the early years, owed much to the Prince, who was well-versed in both political and diplomatic matters and who later invested considerable effort in the country’s recovery as a member of the lower and upper houses of the Czech legislature and afterwards as minister of foreign affairs. His charisma, personal charm and political talent made him a great networker, with excellent contacts in European and global politics, including prominent figures such as Helmut Kohl and Henry Kissinger, who repeatedly referred to Felix zu Schwarzenberg, the Prince’s ancestor, in his iconic work A World Restored.

Noblesse oblige, or nobility obliges, is the well-known French proverb, and for Prince Schwarzenberg, this obligation meant daily work and responsibility for his own communities, large and small, and above all, for democracy and human rights. He was an ardent advocate of the unification of the continent and a true Central European who, at critical moments, was able to rise above the often narrow-minded political thinking that resulted from the divisions of the 20th century. He was a homo politicus, in the positive sense of the word. In many respects, he was a representative of a political habitus similar to that of Otto von Habsburg, for whom politics was a true vocation, not an endeavour carried out for the sake of power and the prestige associated with it. He remained a sovereign thinker until the end of his life, always consistent in his own views, even on controversial issues, including the political and public debates that unfolded over the Beneš decrees after the fall of communism. (His unwavering condemnation of the decrees proved to be a politically risky venture, ultimately contributing to his defeat in the second round of the 2013 presidential elections to former prime minister Miloš Zeman.) However, this consistency in policy-making did not imply a stubborn insistence; his willingness to engage in dialogue helped him find compromise solutions in the often confusing domestic and foreign policy context.

Often describing himself as a Central European with a Swiss passport (Mitteleuropäer mit Schweizer Pass), Schwarzenberg’s political career is an excellent example of how an identity with historically shaped characteristics can be put at the service of regional development and cooperation. Through his family heritage and in-depth political, historical, cultural and social knowledge, he understood the dynamics of the relations between Prague, Budapest, Bratislava, Krakow and Vienna in all their nuances better than anyone else. Furthermore, as a friend of Hungary, with prominent members of the Festetics family among his ancestors, he was instrumental in the search for the remains of János Esterházy, who was being subjected to the conspiracy trials of the nascent Czechoslovak communist regime.

We hold in our Foundation’s archives the correspondence between Otto von Habsburg and Karel Schwarzenberg, which provides an insight into the turbulent period of the regime changes and the subsequent decade of Central European course-setting as well as into his European politics.[1] Their exchange of letters illustrates that the common imperial heritage and the often overlapping loyalties that resulted from it are not anachronistic obstacles but rather the driving forces behind the Central European cooperation.

During her visit in early November, Eva Dvořáková, Ambassador of the Czech Republic in Budapest, toured our collection and leafed through the correspondence between our namesake and the former Minister of Foreign Affairs with great interest. In the course of the conversation, it was suggested that an oral history interview with Karel Schwarzenberg would be an enriching experience. Sadly, this is no longer possible. Nevertheless, his confidence in sound solutions, his intellectual legacy and the political vision he represented should continue to guide the future of Central Europe and the whole of the Old Continent.

Bence Kocsev

[1] From a historian’s point of view, perhaps even more intriguing is the correspondence with the late politician’s father, which provides an interesting record of the Austrian and émigré Czechoslovak politics in the first three decades of the Cold War. The letters addressing political issues are often complemented by insightful excursions into social and cultural history, but the former heir to the throne also asks the Prince for advice on the (political) risks of accepting an invitation to visit the Austrian artist and philosopher Friedensreich Hundertwasser’s studio in Vienna. We do not know whether the visit took place in the late 1960s, but in any case, the Archduke must have made a favourable impression on Hundertwasser, who dedicated his work Für die Wiederkehr der konstitutionellen Monarchie (For the Return of the Constitutional Monarchy) in 1987 to Otto von Habsburg, who had just celebrated his 75th birthday. We also encounter the artist’s name as one of the authors of the Festschrift, edited by Walburga von Habsburg and Bernd Posselt in the same year.