| The cardinal in the company of Zita, Otto, and Karl |

In the article, I highlight some of the stages in the decades-long relationship between József Mindszenty (Pehm) (1892–1975) and Otto von Habsburg, the last heir to the Hungarian throne, and illustrate it with a number of documents from the collection of the Otto von Habsburg Foundation.

József Mindszenty (Pehm) was known among his contemporaries for his loyalty to the king. His legitimism can be traced back to his family upbringing, the religiosity of his home town, the predominantly Catholic character of his wider environment, Zala County, and the courtly traditions of the large landowning aristocracy of Transdanubia. These traits were only reinforced by his years at the seminary in Szombathely and the intellectual and spiritual influence of his bishop, Count János Mikes (1876–1945), which proved decisive throughout his long and eventful life.

In the penultimate year of World War I, the young cleric assigned to the town of Zala quickly became well known in local public life. He never made a secret of his ideological and political commitments. During his twenty-seven years of service there (1917–1944), he continuously built his legitimist image, initially in the town, then in the diocese, and from the early 1930s in the public life of the country after the Treaty of Trianon. During this time, he worked tirelessly to build networks, gather supporters, and promote religious organizations and initiatives. During its Egerszeg period, the Zalamegyei Újság newspaper, which he founded and edited, was an effective opinion-forming tool for the parish priest.

Pehm’s most spectacular undertaking was undoubtedly the construction of a second church, which had long been necessary due to the town’s growing population. The house of God, dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, was built in two years to commemorate the last Habsburg monarch, King Charles IV. It was consecrated on September 25, 1927 (and declared a parish church on January 1, 1942). The widow of the emperor also contributed to the construction of the church pulpit.

| A contemporary postcard of the church | Memorial plaque placed under the pulpit |

After the death of King Charles in 1922, József Pehm’s legitimizm “fell” on Otto, the oldest male member of the imperial family. He first met the heir to the throne in person in 1924, when he made a detour from a pilgrimage to Lourdes to visit the exiled Habsburgs in Lequeitio, northern Spain. The Basque fishing village was a popular destination for Hungarian and Austrian legitimists at the time. His visit was followed by several others, and he continued to visit the family even after Zita and her children moved to Steenokkerzeel, near Brussels, in 1930.

His dedication was appreciated by Hungarian legitimist circles. He became a regular participant in royalist gatherings, and on November 20, 1933, he delivered the homily at the Otto Mass held in the Basilica. The following words were also spoken at that time:

“It is necessary that prayers be said for everyone, including kings. This solemn sacrifice is a request and an act of thanksgiving. We must pray for our country, our nation, and our king with reverence, humility, faith, and the awareness that God’s hand plays on the organ of history and that Providence directs the fate of peoples and nations,” said the abbot to the faithful gathered for the solemn occasion.[1]

The reports do not mention him by name among the participants of the dinner at the Vigadó the following evening, but perhaps he too was a witness to the most violent anti-legitimist movement of the era, during which anti-Habsburg demonstrators broke into the building and caused serious damage to the furnishings during their brief stay.

The second half of the decade passed under a gloomy European sky. With Hitler’s growing influence, the Anschluss, and the subsequent suppression of the Austrian legitimist movement, and with Hungarian domestic politics increasingly shifting toward extremism, little room for maneuver remained for the supporters of the Habsburgs. The heir to the throne and his family spent the years of the World War in North America. Otto worked across the Atlantic on a scenario for the post-war settlement of the Danube Basin within the framework of a federal Catholic state.

Pehm – Mindszenty since August 1942 – József’s path meanwhile led him from being the parish of Zalaegerszeg to become bishop of Veszprém (March 4, 1944). After the turn of events in October, the Arrow Cross Party arrested him and took him to Sopronkőhida, which also meant his release came with the end of the war. After the death of Jusztinián Serédi in March 1945, he was one of those recommended by the Hungarian clergy to the Pope as a possible successor.[2] He was appointed Archbishop of Esztergom on September 8, 1945, by Pope Pius XII.

The Hungarian prelate who traveled to the 1947 Marian Congress in Ottawa found a way to meet Queen Zita and, through Cardinal Spellman, even Otto von Habsburg himself in Chicago. During their conversation, they exchanged views on the post-war situation in Hungary and the state and tasks of the Hungarian Church. This half-hour conversation – or rather its fictitious, conspiratorial content aimed at restoration, created by the communist leadership – formed one of the most serious charges against the cardinal in the trial held in early 1949, which ended with him being sentenced to life imprisonment.

| Cardinal József Mindszenty, Prince Primate, on trial in the Budapest-Capital Regional Court, 1949 Photo: Fortepan / Tibor Bass |

The archbishop was arrested in Esztergom on December 26, 1948, and his sentence was announced on February 8, 1949. Mindszenty did not break down during his years in prison, but news from the outside world did not reach him. He was released during the revolution, but after a few days of freedom, the years of dictatorship returned, which the prelate spent in the US Embassy in Budapest after November 4, 1956. His departure from Hungary was made possible by an agreement reached on September 28, 1971, in line with the Holy See’s policy toward Eastern Europe. During this time, our sources have no information about the relationship between the two men.

József Mindszenty and Otto von Habsburg met again twenty-four years later, on November 29, 1971, in Vienna. During a private conversation lasting several hours at the Pázmáneum, Mindszenty was finally able to speak freely, after years of isolation from the world, with the man whose cause he had felt as his own throughout his adult life and whom he had served as the embodiment of his ideals.

The cardinal’s personal charisma left a deep impression on the former heir to the throne. This is how he later recalled the meeting.[3]

“When I left the Pázmáneum, I felt like I had spoken to the greatest Hungarian of the century. He is the greatest Hungarian since Széchenyi.”

During their encounter, they agreed that József Mindszenty would celebrate a festive Mass in May of the following year, on Zita’s 80th birthday. And so it happened. On May 1, 1972, in the presence of family members gathered in Zizers, Switzerland, the now free cardinal-archbishop celebrated a thanksgiving Mass.

| Zita and József Mindszenty surrounded by family members attending the ceremony Photo: Mindszenty Foundation |

He didn’t forget about Otto’s birthday that year either:

HOAL860

| Mindszenty’s good wishes for Otto von Habsburg’s 60th birthday |

Otto von Habsburg saw the figure of the cardinal living in exile as a symbol, a victim of the power politics imposed on the region, whose resistance gave hope for the overthrow of the existing system:

“…by his mere existence, Prince Primate Mindszenty is a banner and a center… the fact that the Hungarian primate lives in Vienna today… has a strong impact on all those who would like to recognize the permanence of the Yalta line. Mindszenty, even when he does not speak, proclaims loudly in the West that Europe will only be complete when the 110 million Europeans who were torn away by Yalta can one day exercise their right to self-determination. It is precisely the fact that a legitimate representative of a Central European nation lives here that makes it difficult for those who want to perpetuate the status quo at all costs. That is why, when the primate went into exile, many tried to destroy him with their journalism. But they achieved exactly the opposite.”[4]

| József Mindszenty, 1973 |

When Mindszenty received Pope Paul VI’s letter on November 1, 1973, in which the head of the Catholic Church asked him to voluntarily resign from the archbishopric, the cardinal sought out Otto von Habsburg to intervene on his behalf with the Vatican in order to clarify the situation and possibly change the decision. Otto tried to take steps, but his efforts were unsuccessful. The Hungarian archbishop was officially stripped of his title on February 5, 1974.

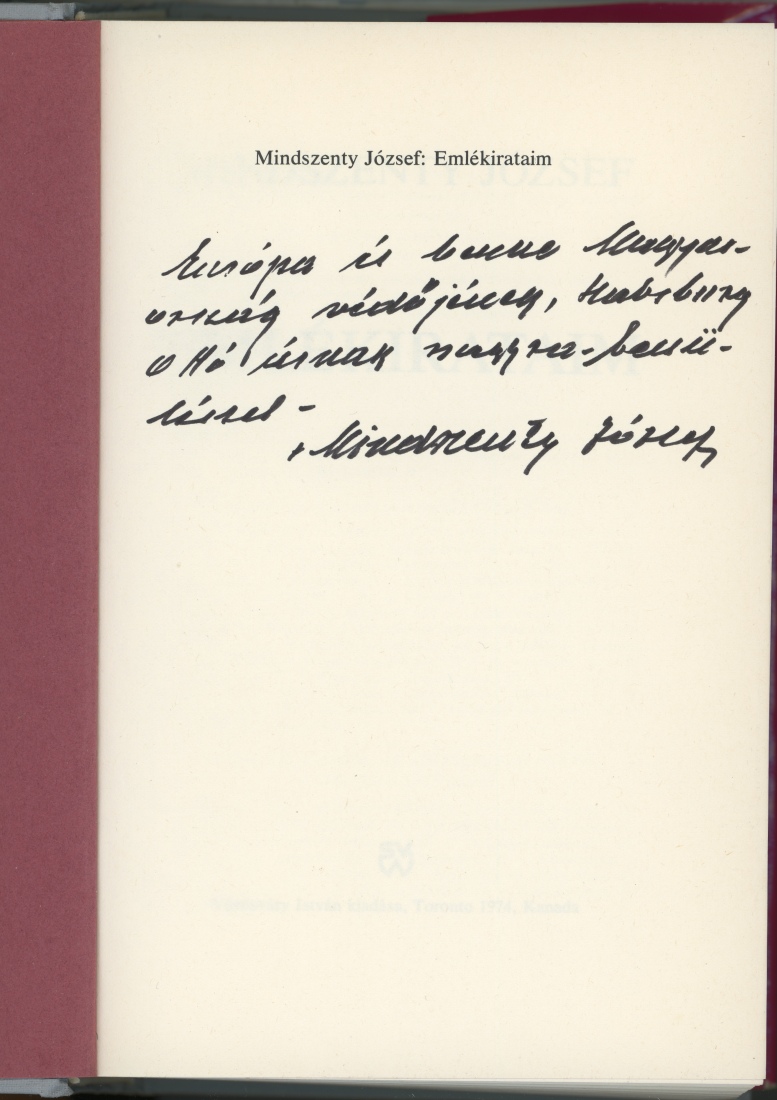

Following these events, the cardinal’s memoirs were published in 1974 by Vörösváry Publishing in Toronto. On the advice of Otto von Habsburg, Mindszenty separated his monumental church history material, written during his years at the embassy, from the corpus, so that the volume primarily summarizes the chronicle of his own personal fate.

| Dedication to Otto by Mindszenty in his memoirs |

In a foreign policy review published in Munich, which gave voice to the views of Otto von Habsburg and European conservative thinkers, the former heir to the throne praised the persecuted 80-year-old Hungarian church leader and set him as an example for the spiritual renewal of the continent:

“Mindszenty’s path was straightforward from beginning to end. In the eight decades of his life, we find no evidence of cowardly compromise or ambiguous agreements with those in power. This, of course, does not please the so-called diplomats, the schemers in office. They disguise their own cowardice as cleverness, and the witness, or martyr, whose faith is a sacrifice rather than a means of livelihood, is a constant reproach to the compromisers. Of course, Mindszenty may have made mistakes here and there, as we all have. But we can say of him that he never betrayed himself or his principles. (…) Mindszenty remained faithful to his God and his people. It is clear that many find this attitude unpleasant in an age of general cowardice and adaptation to “realities.” Dwarfs have always hated giants and tried to drag them down to their own level. (…) This name is synonymous with courage. This name is a program. If Europe ever overcomes its weakness and if Christianity once again becomes a creative force on this earth, it will not be thanks to cowards, nor to those who seek to survive by cheap tactics. It will only be possible if Europe proves itself worthy of Mindszenty.[5]

|

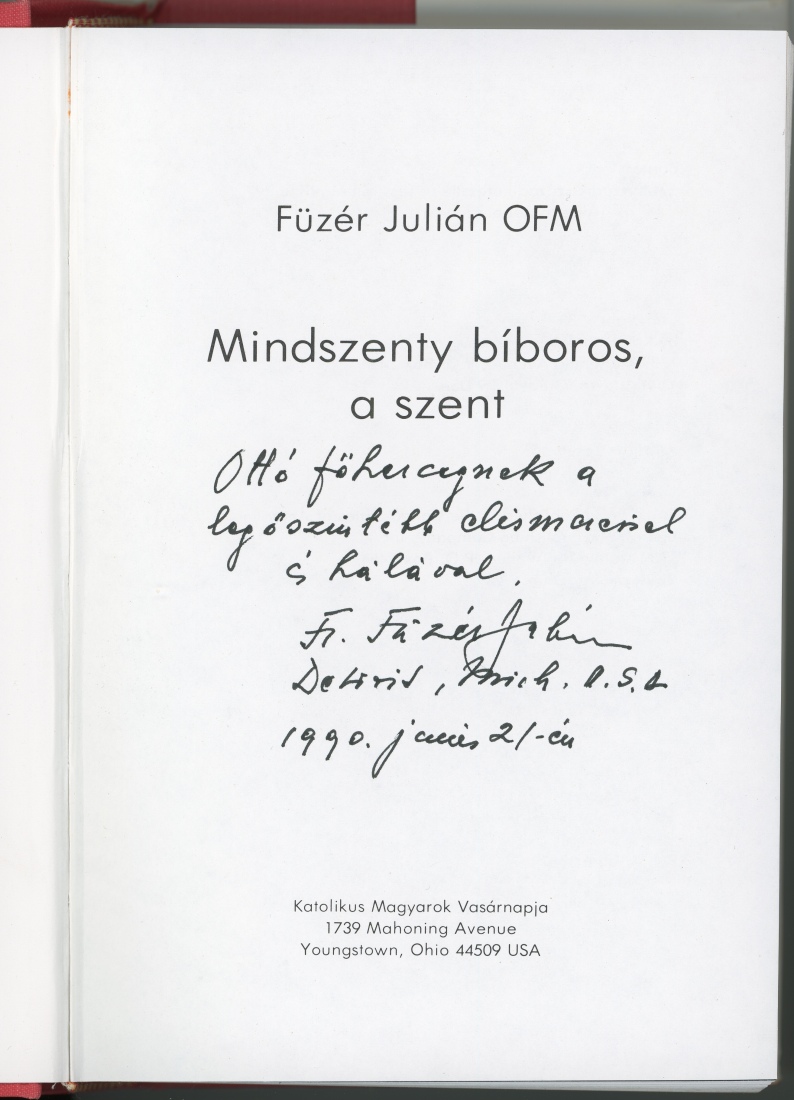

Julián Füzér, Franciscan monk who campaigned for the canonization of the cardinal |

Despite his advanced age, the cardinal tirelessly visited Catholic communities around the world. He returned to Vienna ill from his last trip to South America. He died on May 6, 1975, during surgery at the Hospital of the Brothers of Mercy. In accordance with his last will and testament, he was buried in the Mariazell Basilica on May 15, 1975. Hungarian pilgrims visiting this popular place of worship since the Middle Ages could now also pay their respects at his grave. Otto’s obituary praised his life, the cardinal’s suffering as a sacrifice, and, placing it in a spiritual dimension, spoke of hope for the future:

His example of courage, loyalty, and integrity will bear fruit, and Mindszenty’s personality will have a great impact on future generations. In other words, József Mindszenty’s great era is yet to come. Not only because he has now returned to God and received the reward for his suffering. Mindszenty’s influence will also be felt on earth. For he has shown us what true human greatness is, just as Zrínyi’s heroic death at Szigetvár meant more to the Hungarian people than any clever compromise could ever have done.

In this way, Mindszenty saved the soul of his country and, with it, his homeland during the most difficult hour in its history. In the history of every nation, there is a great figure who, after his earthly life has ended, reaps decisive victories. … In our time, this figure was the Primate for our homeland and our church. For in an era of general cowardice, debasement, and loss of dignity, it was he, Mindszenty, who showed that the old truth still holds true today: sanguis martyrum, semen christianorum. The blood of martyrs is the seed of Christianity, and this is as true in the 20th century as it was in the days of the Roman catacombs.[6]

Mindszenty considered the site temporary, as he hoped that after the departure of the occupying Soviet troops, his remains would eventually be laid to rest in Esztergom. His wish was fulfilled on May 4, 1991. Otto von Habsburg was present at the event in Mariazell, accompanied the convoy to Hungary, and was among those who paid their last respects to the nation’s Catholic martyr bishop in the crypt of the basilica in Esztergom.

In 1989, the Hungarian church requested a retrial in the Mindszenty case. During the proceedings, Otto von Habsburg was also heard.[7] It was not until March 2012 that the Prosecution Service of Hungary announced a full moral and political rehabilitation.

His memory and spiritual legacy are preserved by the Mindszenty Foundation, which he initiated and registered in Vaduz in May 1972. Its first director was the son of Blessed László Batthyány-Strattman, Iván. Since 1994, the foundation has continued its activities through its Hungarian partner organization, currently headed by Eduard Habsburg-Lothringen, a descendant of the Hungarian branch of the Habsburg family and Hungary’s ambassador to the Holy See, who succeeded his father, Mihály, in this position. The foundation published a new edition of Mindszenty’s book, Emlékirataim (My Memoirs), in 2024.

Ferenc Vasbányai

[1] Uj Nemzedék, November 21, 1933, p. 7.

[2] For more information about the circumstances surrounding the nomination and the adventurous and eventful life of Jesuit Töhötöm Nagy, who served as a courier between Hungary and the Holy See, we recommend Éva Petrás’s book: Álarcok mögött. Nagy Töhötöm életei. Budapest–Pécs, ÁBTL–Kronosz, 2019.

[3] Emil Csonka: A száműzött bíboros. San Francisco–München, Új Európa, 1976, 105.

[4] Mindszenty Bécsben. Új Európa, 1972, 11, 7.

[5] Mindszenty neve örök. Új Európa, 1974, 2, 7.

[6] A jövő győztese. Új Európa, 1975, 4, 5.

[7] We recommend the following publication: Habsburg Ottó és az államhatalom. Levéltári források az utolsó magyar trónörökösről (ed. Kocsis Piroska, Ólmosi Zoltán. Budapest, Habsburg Ottó Alapítvány–Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár–Corvina, 2020), in which documents related to Mindszenty can be found on pages 119–126.

*

Works by József Mindszenty in Otto von Habsburg’s library

Mindszenty József: Emlékirataim. Toronto, Vörösváry, 1974. (dedikált), német nyelven: Erinnerungen. Frankfurt/M.–Berlin–Wien, Propyläen–Ullstein, 1974.

Mindszenty József: Hirdettem az Igét. Válogatott szentbeszédek és körlevelek. 1944–1975.

[Bev. és vál. Közi Horváth József] Vaduz, Mindszenty Alapítvány, 1982.

Mindszenty József: Napi jegyzetek. Budapest, Amerikai Követség. 1956–1971.

Vaduz, Mindszenty Alapítvány, 1979.

Mindszenty (Pehm) József: Az édesanya. Budapest, Hunikum, 1990.

(With the printed text: “This book is copy no. 5 for Otto von Habsburg.”)

*

Mindszenty literature among the books of the heir to the throne

Adrányi, Gabriel: Die Ostpolitik des Vatikans 1958–1978 gegenüber Ungarn. Der Fall Kardinal Mindszenty. Herne, Schäfer, 2003. (Studien zur Geschichte Ost- und Ostmitteleuropas) (dedicated)

Csonka Emil: A száműzött bíboros. San Francisco – München, Új Európa, 1976. (dedikált), in German: Vasari, Emilio: Der verbannte Kardinal. Wien–München, Herold, 1977.

Eszterhás István: A bíboros és a rendőr. Regény. Cleveland Heights, Ohio, Szerző, [1985]. (dedicated)

Füzér Julián: Mindszenty bíboros, a szent. Youngstown, Ohio, Katolikus Magyarok Vasárnapja, 1989. (dedicated)

Gruss aus Mariazell. Im Mindszenty-Gedenkjahr 1985 (periodical publication)

Harckocsival Mindszentyért. [Összeáll. Hornyák Tibor] Budapest, Hornyák T., 1991.

Ispánki Béla: Az évszázad pere. Megszólal a tanú. A Mindszenty kirakat-per ismeretlen adatai. Toronto, Vörösváry, 1987.

Jaszovszky József: Mindszenty, a főpásztor Észak-Kaliforniában. Menlo Park, [Calif.], Szerző, 1980. (dedicated)

József Mindszenty devant le Tribunal du peuple. Budapest, Editions d’Etat, 1949.

Kovách Aladár: A Mindszenty per árnyékában. Dokumentumok, pásztorlevelek, rendőri utasítások, tiltakozások, jegyzetek. Innsbruck, Archivum Hungaricum, 1949. (dedicated)

Közi Horváth, József: Kardinal Mindszenty. Ein Bekenner und Märtyrer unserer Zeit. Königstein-Taunus, Kirche in Not–Ostpriesterhilfe, [1976].

Lesourd, Paul: Héros, confesseur et martyr de la foi. Le cardinal Mindszenty, primat de Hongrie. Paris, France-Empire, 1972. (dedicated)

Mihalovicz, Sigismund: Mindszenty. Ungarn, Europa. Ein Zeugenbericht. Karlsruhe, Badenia, 1949. (dedicated)

Mindszenty-Dokumentation. I–III. Bearb. und. übers. von Josef Vecsey und Johann Schwendemann. St. Pölten, Verl. des Pressverein-Druck., 1956–1959.

A Mindszenty-per. [Compiled, with a foreword and biography of József Mindszenty, notes and annotated index by Jenő Gergely and Lajos Izsák]. Budapest, Reform, 1990.

Swift, Stephen K.: The Cardinal’s story; the life and work of Joseph, Cardinal Mindszenty, Archbishop of Esztergom, Primate of Hungary. New York, Macmillan, 1950. (dedicated)

Szalay, Jerôme: Le cardinal Mindszenty, confesseur de la foi, défenseur de la cité. Paris, Mission catholique hongroise, 1950. (dedicated – with printed recommendation to Otto)

Szentnek kiáltjuk! Emigráns magyarok Mindszenty bíborosról halála 10. évfordulóján. Összegyűjt. és s. alá rend. Füzér Julián. Youngstown, Ohio, Katolikus Magyarok Vasárnapja, 1987.

Weissbuch. Vier Jahre Kirchenkampf in Ungarn. Zürich, Thomas, [1949].

*

The assessment of Mindszenty’s character and his role in Hungarian church history – supplemented by the precise and thorough work carried out by Ádám Somorjai OSB during his time at the US Embassy, collecting and publishing sources – amounts to a library’s worth of material. This cannot be complete without a biography of the cardinal’s life, written in the most thorough manner, in a way befitting his significance, and covering even the smallest details:

Balogh Margit: Mindszenty József (1892–1975) I–II.. Budapest, MTA BTK, 2015.

She also compiled the chronicles of the early years with similar thoroughness:

Balogh Margit: Az apát úr. Pehm (Mindszenty) József zalaegerszegi évei. Zalaegerszeg, Göcseji Múzeum, 2019.

We recommend the following works by Catholic (clergy) authors from the latest literature:

Török Csaba: Prímás album. Budapest, Magyarországi Mindszenty Alapítvány, 2016.

Török Csaba: A szent életű bíboros. Budapest, Magyarországi Mindszenty Alapítvány – Új Ember, 2016.

Just like the demythologizing approach of the historian known for his polemical tone:

Ungváry Krisztián: A Mindszenty mítosz. Értékek és választások. Budapest, Open Books, 2023. (Befejezetlen múlt)