The evening, organised by the Otto von Habsburg Foundation and the Royal Palace of Gödöllő, was introduced by Gergely Prőhle. The director of our Foundation emphasised that the principles and example of Charles IV are significant not only for the understanding of European and Hungarian history but the character and mentality of his son can also be traced back to this.

István Rákóczi, a researcher on the history of relations between Portugal and Hungary, reminded us that historians had already spun fictitious links between the dynasties of the two countries in the Middle Ages and that these had become real ties over the centuries as the Habsburgs had taken on a prominent political role.

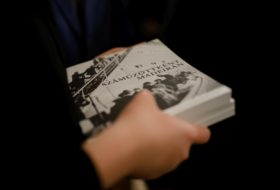

Moving on to the 20th century, Sándor Szakály, Director of the VERITAS Historical Research Institute and Archives, highlighted the reader-friendly, not overly scholarly nature of the volume, which was compiled from the material presented at a conference in Gödöllő in the spring. He said that although the discussed events are from a hundred years ago, our image of them may still be evolving: he cited as examples the value of the source material of forgotten writings published in the 1920s and events such as the meeting between Miklós Horthy and Otto von Habsburg in the 1950s, which so far have no known written record. Szakály also does not see the debate about Otto’s potential later political role in Hungary as closed: in his view, Horthy did not for some time reject the possibility of handing over power to a ruler of his choice (even a Habsburg) – an option left open by the wording of the law on the dethronement of the dynasty.

Dávid Ligeti, researcher at VERITAS, has spoken about new perspectives on the studies. For him, the focus on the person of Charles seems to be of importance, as Gergely Kovács indicates in his article on the beatified monarch. Ligeti believes that our post-1945 historiography is primarily responsible for the negative perception of Charles’s political activities but that the one-sided view has become much more balanced in recent decades, as it has been for so much else in the 400 years of the shared Monarchy. Due to this change, Austrian historians are now more focused on Charles’s role as King of Hungary.

Gergely Fejérdy, one of the book’s editors, praising the corpus focusing on the exiled family’s everyday life in Madeira, spoke about the opinions that still exist today but can be refuted based on the documents. Among these, he mentioned the family’s total lack of money, which prompted them to move from Funchal to a mountain villa far from the coast (the variability of climatic conditions may have been to blame for the tragedy that occurred.) The Foundation’s deputy scientific director said that the main reason for the move was that the family was fed up with the inconvenience of tourists and had sought a more inaccessible place to live on the island. The notes of the governesses who served alongside the family also offer a new perspective, bringing the reader almost intimately into the lives of the children and their parents, their physical and mental conditions (their illnesses, their toys, their upbringing, and their visits to Holy Masses and their holidays). The diaries can also help to clarify the image of Queen Zita, whose loving strictness, stubbornness and perseverance towards her children were much needed during her life with her husband, but especially during the decades of her widowhood. Her energy never waned as she prepared Otto to rule, and she long believed that she would see her son on the throne.

On behalf of the Portuguese guests of honour, Miguel Filipe Machado de Albuquerque, Head of the Regional Government of Madeira, thanked the organisers for their work and praised the volume, which was the result of a joint effort. He said that the legacy of Charles had been a part of Madeira’s cultural memory for a hundred years (‘the emperor is in the heart of the people’) for a simple reason: the things that last longest in the culture and the heart defy the passage of time.

Mária Schmidt has put the First World War, the post-war settlement and the 100 years since then in a global and geopolitical framework. The Director General of the House of Terror Museum praised the Habsburgs’ brilliant statesmanship, which enabled the Danube Empire to defend central Europe from German, Russian and Turkish invasions for centuries. But the crucial international network of their dynasty was dismantled by the short-sighted decisions of the peace treaties around Paris. These things soon led to the region falling prey to the National Socialist and Communist ideologies. The researcher argues that thirty years after the regime change, the current powers in the West are still prisoners of the patterns that were fixed in 1918-20 as if forgetting how the Monarchy’s multi-ethnic, multi-cultural kaleidoscope represented a rich, liveable world. “The wound in the heart of Europe will never heal until it has the mortar of mutual respect, of recognition of common interests and goodwill,” she concluded.

More information about the exhibition is available here

Photos: Zoltán Szabó