Exiting the negative spiral

With our accession to the EU, a centuries-old Hungarian aspiration was realised: to participate institutionally in shaping the destiny of Europe. In addition, support comparable in amount to that of the Marshall Plan arrived in the country. Yet we have entered a negative spiral in our relations with the Union.

At the time of Hungary becoming a member state, I had already been working as a diplomat in Bern for a year and a half, a country where the civil revolution had won in 1848 and where the federal system had led to a highly successful model of integration. Outside the EU. Supporters and opponents of EU membership were roughly equal in strength among the Swiss, although the then ongoing process of making the Swiss banking system EU-compliant and transparent did not benefit the EU’s image in the Alpine country. Our entry into the European Union did not attract much interest either, and the celebrations were not held in an elegant concert hall, but at the residence of the Ambassador of the Czech Republic, almost exclusively in a diplomatic circle. The majority of the European ambassadors accredited to Bern were experienced old stagers, towards the end of their careers. So there was a chance for a substantive exchange of views during the usual conversations, and the turn of events in Swiss political life always gave rise to some indignation in the EU ambassadorial circle, which, I admit, sometimes surprised me. And although I have never felt, and still do not feel, any sense of inferiority or defiance towards Western politicians and diplomatic colleagues, when I encountered the lecturing gestures towards Switzerland, I sometimes wondered what many of them might think of us.

I find it absurd

I didn’t have to wait long to find out. We were around midnight on the day of Hungary’s accession when the ambassador of a relatively small EU founding member state, who was in his 60s, turned to me and said quite plainly, ‘You know, Gergely, I like you as a person, – he began, – we always have a good chat, we both know history, I know how much injustice your country has suffered behind the Iron Curtain, but for Hungary to join our club now, I find it completely absurd, and I don’t think it will end well.’ The experienced colleague’s voice was monotonous, laconic rather than impetuous, as if he had been preparing to utter the frank sentence for a very long time. I found it difficult to speak. It would have been an inept gesture to try to respond with a humorous remark, but there was no point in being angry with him either. I recalled the negotiations of previous years which have had their own particular atmosphere. My years in Berlin was the time when we knew that the key to many doors in Brussels had to be sought in the German capital, when we were often the first of the states seeking to become members to bring a negotiating process to a close, when, on one of his frequent visits to Berlin, Gyula Horn, who was revered as a saint in Germany, banged his fist on the table and demanded that he be informed immediately about the exact date of our accession. And then I remembered the words of János Martonyi, whom the otherwise not always friendly Joschka Fischer had always listened to with wide-open eyes whenever the future of Europe had been discussed. Just so, the image of Ferenc Mádl, receiving an honorary doctorate at the University of Heidelberg, came to my mind, with the professors around him in an almost sacred reverence for a man who they knew had been concerned with the fate of the Old Continent even during the years of the communist regime. But I could also mention Péter Gottfried, Chief Advisor of the Prime Minister, or my predecessor as ambassador, Péter Balázs – both of whom were widely recognised experts on EU affairs. But most of all, of course, I was thinking of what I had heard in my own family: there was never, not for a moment, any doubt that, civilisationally, rationally and emotionally, we belonged to where so many people, including our relatives, had gone in 1956. Then this man came to tell me that, for him, this accession was absurd and that it would not end well.

Always five years away from becoming a member

I couldn’t get this short conversation out of my head for a long time. What annoyed me the most was that this man certainly was not aware of the things that we should have actually been worried about. After all, compared to many other new member states, Hungary’s economy was not exactly on an upward trajectory when it joined the EU: the handouts of the Medgyessy Government and the eye-wash of the first Gyurcsány Government in terms of economic policy indicated that things would be different for us than in Poland, let alone the Czech Republic, where economic growth had taken off with accession. At the time, we often quoted former Polish Prime Minister Hanna Suchocka: ‘It’s just strange that we’re always five years away from joining the EU’, as the one and a half decades from the change of regime to accession had been a long time indeed. Moreover, in many enlargement scenarios, our country had consistently been considered at the top of the list, we had been the first to conclude trade agreements with the European Economic Community, but in the end, for various geopolitical, historical and economic reasons, the round of the ten states was decided. In other words, regardless of the set of criteria, the decision on which countries would become members of the European Union and when, was ultimately based on political factors.

Clear commitment to the EU

On a historic scale, of course, a few years are of little significance, and there is nothing to obscure the fact that Hungary’s membership was the will of the overwhelming majority of Hungarian society. This is unquestionable even in the light of the experience of our twenty years in the European Union, which has not been without controversy. In conclusion, it is important to state that the actuality of our membership, as well as the latest Eurobarometer data, according to which seventy-seven per cent of Hungarians believe that our country benefits from being a member of the EU and only one in sixteen think that it causes detriment, indicates a firm basic position and a clear commitment to the EU, despite all the political upheaval, domestic bureaucracy and withholding of resources by Brussels.

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that emphasising the historical meaning of the twentieth anniversary should not lead us to lose sight of the apparent problems. Just as we cannot overlook the fact that on the 1st of May there were no meaningful government commemorations, and on Europe Day – coincidentally the Feast of the Ascension – the country was occupied with the visit of the Chinese president. Nor can we say that the EU of today is still the same as it was twenty years ago, we ourselves could even call certain developments and political statements ‘absurd’, and probably even my old colleague, the former ambassador to Bern, would agree with us, especially if he compared the situation of the EU today with the intentions of the founding fathers or even with the European politics of the time of Helmut Kohl and François Mitterand.

The EU funds that had come in on our accession had been used to make up the shortfall rather than to achieve spectacular growth, given the weakness of our economy. Less than two years later, after the 2006 protests in Hungary, the country was in a state of political paralysis, with domestic political struggles and economic woes distracting attention from the possibilites of common assertion of interests, and the Hungarian government’s economic policies led to the country being swiftly faced with an important EU disciplinary instrument: the infringement procedure. Those who had seen EU membership as a way of revising the unjust decisions of Trianon, found that the Union could not be counted on to give any meaningful, direct attention to the rights of national minorities.

Success in separating political accusations from legal arguments

A crucial moment was when, after Fidesz had achieved a two-thirds majority in 2010, José Manuel Barroso, who was otherwise on good terms with Viktor Orbán, refused to ease the restrictions on the government’s scope of action, leaving the leadership of the country to resort to alternative methods under duress of the infringement procedure. The introduction of bank and other taxes sparked a major outcry from influential business circles, making them to actively lobby at EU level for the abolition of the system of ‘levies’. This was compounded by the European debate on the new Hungarian Media Law, which was not unrelated to the perceived or real grievances of the banks, as many of the media owners had links to them. Regardless of the real significance of the financial wrongs and the strictness of the media law, the two measures have succeeded in uniting the pro-market liberal, more right-wing forces with the mainstream left-wing movement advocating human rights and freedom of speech. This was a unique achievement. The debate on the fundamental laws and the new Constitution had to be conducted in this light, or rather in the shadow of it. It should be noted, however, that in the vast majority of cases it proved possible to separate the political accusations from the legal, professional arguments concerning Hungarian legislation and thus to reach an agreement with the Commission. The constant debate did not, of course, improve the mood of the negotiating parties on either side, but the domestic side found that the struggle with Brussels, the sovereignty battle, strengthened the ‘national base’ in Hungary and led to more and more victories in elections.

The increased flow of migration in 2015 opened a new chapter in our confrontation with mainstream European communication. The firm opposition of the Hungarian government, the concrete act of building a fence, combined with a political campaign that had been brutal in its refusal to allow the entry of migrants, had made Hungary subject to a wave of political criticism, the repercussions of which could little be mitigated by the fact that a few years later the Hungarian position on the protection of borders was basically incorporated into EU documents. The extent to which political communication aspects had determined the course of the discussion on Hungary was well illustrated by the 2017 Angela Merkel-Martin Schulz debate on German public television. It was rather peculiar, to say the least, that in a German domestic policy debate ‘the Hungarian case’ was repeatedly brought up as a bad example that had to be fought against. The vilification of the Hungarian government has taken on a life of its own, somewhat detached from the real political developments, based on half-truths, with the help of clearly devious political advisers.

The slogan he chose was ‘Strong Europe’

The same happened at home. The rapid pace of political communication, its tendency to be vociferous, the use of reductive terms and, in general, the constant campaign rush have put the discourse on the Union and relations with the West in a negative spiral. In Hungary too, and not without cause. As it is undeniable: Europe, with its deteriorating economic competitiveness figures, its continuous distancing of the rules of social coexistence from traditional Judeo-Christian values, its rightful but often over-ideological commitment to climate change and sustainability, is not without good reasons being criticised by the government and the prime minister who chose ‘Strong Europe’ as the slogan of the widely acclaimed Hungarian EU Presidency in 2011.

We could and should analyse at a greater length the development of the disputes between the EU and Hungary on such important issues as corruption, the Russian-Ukrainian War or the independence of institutions, especially higher education. Each of these is an important, fundamental matter for Hungarian civic consciousness, representing a kind of civilisational base. It is crucial to see how Hungarian government policy and the European Union will deal with these issues, and whether they will be able to exit the negative communication spiral and move forward in a sensible direction that will serve the healthy development of Hungarian society, the economic prosperity and competitiveness of the country and Europe.

There can be little doubt that Hungary has gained a lot from the last twenty years of its membership in the EU, and the numbers of progress speak for themselves. We owe this to our own efforts and the work of tens of millions of taxpaying citizens of Western Europe. Hungary may be right about many things when it comes to defending traditional European values, but we should not delude ourselves in vain with the recently recurrent notion of a ‘self-reliant nation’, without allies we can hardly assert our position widely.

Without denying the importance of transatlantic and eastern connections, we cannot delay any further in reinforcing our relations both with the countries we have been institutionally linked to for 20 years and with the EU itself. In other words, we have to break the negative spiral, we need to make it clear that our policy stands by our principles, but is open to compromise. Especially because we are only a truly relevant partner in the East and overseas if we are a successful member of the European Union.

Gergely Prőhle

The author is former Ambassador to Berlin and Bern, Programme Director of the John Lukacs Institute of the University of Public Service and Director of the Otto von Habsburg Foundation.

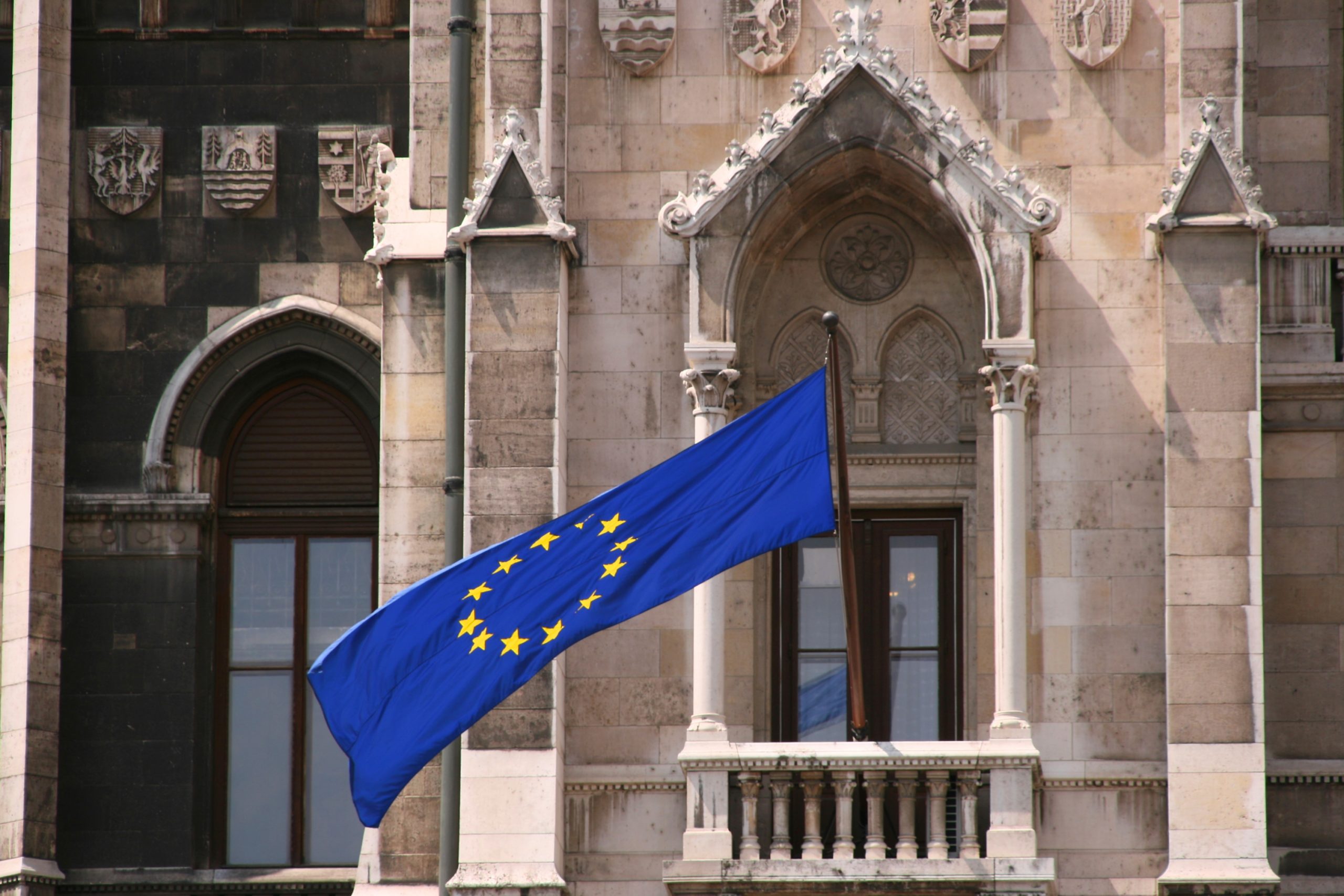

Cover photo: Marek Ślusarczyk (www.microstock.pl.)