The Otto von Habsburg Foundation’s photographic collection consists mainly of images related to our namesake but also includes a sizeable amount of material on the last Hungarian royal couple, Charles IV and Zita. Entrusted in our care are official portraits taken during Charles IV’s childhood, showing the Habsburg family’s everyday life or dating from his curtailed reign. However, the most considerable portion of the pictures depicts military events: visits to the front, medal bestowals, scenes from field life, and army parades.

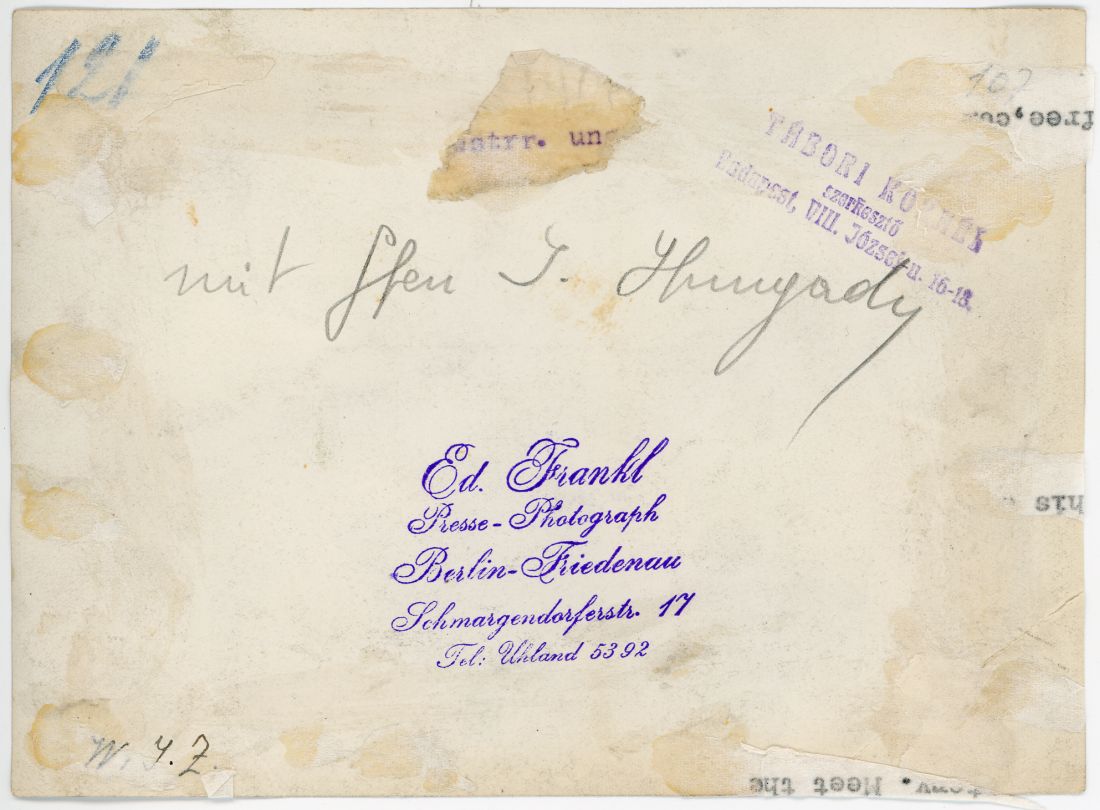

While working on the unit called “The First World War Collection”, we came across the following photograph of Charles in his military uniform in the company of Count Joseph Hunyady. Count Hunyady was already Charles’ aide-de-camp when he was heir to the throne, and after his accession to the crown, he served as the Royal High Senechal. He remained loyal to his ruler after the collapse of the Monarchy, following him to Switzerland and then Madeira. He supported his former king throughout and was his most trusted confidant until his passing in 1922. This high-quality image captures a rare moment, as, apart from a few blurred battlefield shots, the two of them are mostly photographed later, during the years of exile. However, this shot was certainly taken earlier, and judging by the buildings, it was somewhere in the Monarchy. The inscriptions on the reverse of the photograph included no specifics either, but they did provide some additional intriguing information, leading us to follow this lead for identification.

Front and back of the photograph

Reference: HOAL I-5-a 2-4

In the history of humankind, the First World War was the first major military conflict to be thoroughly documented through photographic and motion picture techniques. All the participating nations used visual means to record the events to inform, influence and spread propaganda to the masses. Alongside official government activity, Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy commissioned civilian photographers to create imagery supporting war aims. One of them was the press photographer Eduard Frankl from Berlin. He was a civilian employed by the military authorities, and from 1914 onwards, he travelled the battlefields, capturing both the military and civilian aspects of the war. Although Frankl handed over his negatives to the German and Austrian army headquarters, he kept the positive copies for himself and resold them. His clients were primarily editors of weekly newspapers or magazines throughout Europe, who could use these newsworthy images as illustrations. The stamp of Frankl’s photographic studio appears on the back of our picture as well; thus, we can assume the source, but there is another stamp on it, indicating that it was also used in Hungary.

Kornél Tábori (originally Tauber) was a legendary figure of the early 20th century, one of the pioneers of crime journalism and author of popular volumes on the Budapest underworld. His diverse interests—and his well-chosen subjects—led him to publish a series of volumes ranging from the confiscated letters of Lajos Kossuth, through humorous political anecdotes, to the spiritists of Pest—and he was also the first to translate the detective stories of Sherlock Holmes. He is credited with the first nationally published album of socio-photographs as well: Egy halálraítélt ország borzalmaiból, razzia a budapesti nyomortanyákon (From the Horrors of a Death Penalized Country, Raids on the Slums of Budapest), in which he captured the impoverished Budapesters living in increasingly deprived conditions after the war. During the First World War, Tábori himself worked as a war correspondent, and in 1915, as editor of the Pesti Napló, he published Háborús album. A világháború történelme képekben (A War Album. The History of the World War in Pictures), which depicted the war events and everyday life in 1914-1915. The volume was a massive success with Pesti Napló subscribers, who wrote hundreds of letters thanking the paper for the “precious gift”. In his foreword, the editor points out that they tried to collect images from the broadest possible range of sources and that the selection was made with Hungarian aspects in mind. In addition to the “professional” battlefield reporters, pictures were also obtained from several private individuals, agencies and German newspapers. In the book, Tábori borrowed our picture taken by Eduard Frankl, put his stamp on it as editor, and published it with the inscription “Crown Prince Charles Franz Joseph in front of the headquarters, accompanied by Count Hunyady”. The time and place of the photograph were not specified, and, as the location of the headquarters changed frequently due to the movements of the front, many possibilities could be considered for its identification.

The exact location of the photograph was finally determined by another picture from Tábori’s publication, also by Eduard Frankl, which also appears in a Polish location photo database. It was taken on the Eastern Front at Galicia and depicts a street in the small southern Polish town of Nowy Sącz with high-ranking military officers. A few blocks away, with recognisable architectural features, the place of our picture can be identified. At the time he received the picture, Tábori had no idea that 30 years later, he would be murdered in another town in Lesser Poland, the nearby Oświęcim (Auschwitz). Neither did he know that in 2010, a memorial plaque would be unveiled in his former residence at 16 Krúdy Gyula Street in Budapest in honour of his son, György Tábori, “an outstanding figure in international theatre”.

The location of the picture today (Jan Długosz High School No 1)

We also managed to solve the question of the date of the photograph: since the Austro-Hungarian Army High Command (Armeeoberkommando) was stationed in Nowy Sacz from 13 September to 11 November 1914, we can assume that the photo was taken during this period. These were difficult days of the war, and the Austro-Hungarian forces could only withstand the Russian onslaught with great effort. Military successes and temporary relief were brought only by the breakthrough at Gorlice, which came soon after. Captain Karol Wojtyła, a professional officer of the Monarchy, fought in the battle, which took place about 40 km from Nowy Sacz. The father of the future Pope John Paul II—as the Holy Father himself told Queen Zita, according to Archduke Rudolf’s recollections—named his son Charles out of respect for the monarch – who would beatify his father’s emperor 90 years after the image was taken.

How did this photograph end up in the Otto von Habsburg collection? At the moment, we do not have a clear answer. As in many other cases, it is possible that an admirer or correspondent sent Otto the picture of his father and Count Hunyady. Nevertheless, the lesson to be learnt is that in the course of processing the collection, the examination and identification of historical photographic documents leads through many layers to be unravelled, illuminating many details of Central European history and the specific interweaving of human destinies.

Szilveszter Dékány

Zita Lőrincz