Historians still research and debate who stood by us as friends in the difficult moments of the 1956 revolution, and who dilly-dallied on the international platform.

The 45th anniversary of the revolution reached me as ambassador in Rome and the 60th as ambassador in Madrid. Members of the Hungarian diaspora – more in Italy, less in Spain – are either ’56 refugees themselves, or their descendants, or at least are well acquainted with the events. These stories have not been put down on paper before, so there is a danger that, as time goes on and eyewitnesses dwindle, we will not know the personal destiny of our compatriots stranded in different corners of the world. In Rome, a historian PhD student began the collecting work. Fifteen years later, in Madrid, with the support of the 1956 Memorial Committee, I launched a project to learn about and collect the life stories of the 56 refugees who began a new life in Spain. Our other goal was to revive how the host country treated them and the revolution itself.

Castellana 49. The building of the Hungarian Royal Embassy.

(Source: ABC)

The result of the project is the Spanish-Hungarian bilingual book by Kata Sára Gyuricza and Dr. Péter Gyuricza: The Life-Changing Revolution. Hungary, 1956, which processed not only the written sources, but also the personal memories, the oral history. In the course of their work, the authors show in detail that the 1956 revolution, Spain and the name of Otto von Habsburg are closely intertwined.

The Spanish relations of the Habsburgs are centuries old and persisted even after the loss of the throne after the Spanish Succession Wars (1701–1714). Otto von Habsburg himself was at home in the country, as he was nine years old in 1922 when his widowed mother, Queen Zita, and the entire royal family moved to the Basque city of Lequeitio for seven years. Following his studies, after World War II, Otto von Habsburg returned to Spain, where Franco often used his extensive foreign policy experience. We know from the research of historian José Luis Orella, who was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Hungarian Order of Merit, that Otto von Habsburg wrote “strictly confidential” reports to Franco and his foreign minister. Otto was the founding director and president of CEDI (European Documentation and Information Centre), established in 1952 in Santander, Spain.

Based on the research of Ádám Anderle, it became clear that Spain was the only state to offer military assistance to Hungary in 1956. In addition to acknowledging the heroism of the “Pesti srácok”, the ’56 sympathy also had a practical explanation: General Franco benefited the Hungarian anti-communist uprising ideologically, as he could prove the nature of Soviet rule to the whole world in black and white, from which he saved the Iberian Peninsula. The “Generalísimo”, the winner of the bloody civil war of 1936-39, which claimed many lives on both sides, consolidated his power by the 1950s and sought to return to the international stage. The boycott of the country began to dissolve by him succeeding in restoring diplomatic relations with the United States. This was followed in 1955 by the country’s accession to the United Nations.

The Hungarian Royal Embassy was officially in Madrid until 1944, but due to the historical situation, no new diplomat was sent from Budapest at that time. A padlock was put on the embassy building on Castellana Avenue. From 1944 to 1969, there was no official diplomatic relationship between communist Hungary and fascist Spain. It was not official, but a kind of Hungarian representation still operated in Spain, thanks to the diplomat Ferenc Marosy. Who was he? Between the two world wars, he served in the press department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, then in the Hungarian embassies in Madrid, London, Cairo, Zagreb, and finally in Helsinki. He did not want to join the service of communist Hungary, so in 1946 he went to Spain. As he wrote, “it was the only truly neutral country in the Yalta-ruled Europe.” In Madrid he then appointed himself ambassador and organized the Hungarian community.

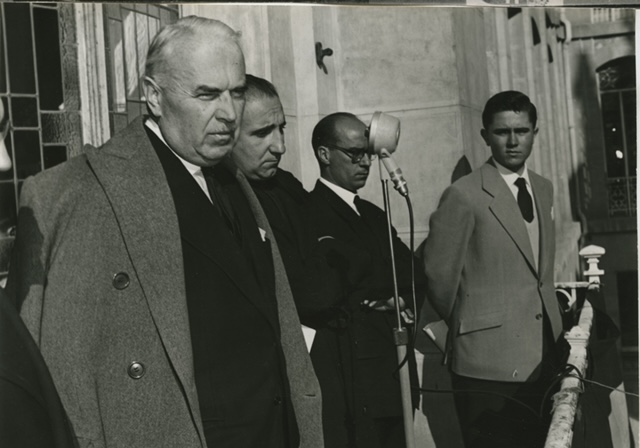

In the autumn of 1956, Ferenc Marosy accepted a donation at a school

(Source: ABC, photo: Teodoro Naranjo Dominguez)

In January 1949, he welcomed Otto von Habsburg arriving in Spain at the airport. Their lives on that day were forever connected. Marosy gave a reception in honour of the Archduke. During the evening, Otto von Habsburg called Marosy aside and said that Franco would see him the next day and asked Marosy to give advice on what to ask for the Hungarians. Marosy wrote the list in the morning, through which Otto von Habsburg asked Franco for his support on three issues: 1. to open the building of the Royal Embassy in Madrid; 2. as in the case of Polish emigration, there shall be broadcast in Hungarian on Madrid Radio; 3. to facilitate the entry of expatriate Hungarians. The next day, Franco read the list and wrote: approved. From then on, Marosy could act as an ambassador recognized by Spain, representing royal Hungary, which did not actually exist in this form at the time. The Hungarian broadcast of Madrid Radio began in 1949 with a message from Otto von Habsburg. Ferenc Marosy, who informally controlled the radio, regularly informed György Bakách-Bessenyey, a member of the Hungarian National Committee dealing with foreign affairs, and sent a copy of his notes to Otto von Habsburg as well.

“Homeland we have no more – but we are still Hungarians,” says Marosy in his memoirs. He considered it his duty to help all his compatriots. He gave those arriving without papers documents from the embassy’s stock, which were accepted in Spain, and no one cared that they would no longer be valid in official (communist) Hungary. He kept the diverse Hungarian community together with the national holiday receptions he organized. Some had Marosy as their godfather, some had him as wedding witness, for some he had given a visa, for some he had a suit made.

After 1949, every occasion when Otto von Habsburg was in Madrid, he visited the reopened royal embassy, even stayed there from time to time. He also used his personal American connections to get Marosy an existence (salary) at the embassy. He achieved this with the help of the Hungarian National Council. When Council support dropped significantly, Otto von Habsburg sought help from American businessmen so that Marosy could continue his work. Ferenc Chorin, Pál Fellner, Ede Vegvari Neumann and Imre Végh, then László Páthi and István Korányi, and finally Baron Thyssen-Bornemissza covered Marosy’s expenditures in Madrid for years. The royal embassy was finally closed in 1969, when the foreign policy climate dissolved and diplomatic relations were soon re-established between Madrid and Budapest. Ferenc Marosy remained in Spain and died there in 1986. The inscription on his tomb is “SZKV” (presumably “Castaway”). It would be interesting to know what happened to the furnishings and documents of the embassy building on the Castellana promenade (later demolished). So far, no credible information has been obtained on this.

The autumn of 1956 brought not only a historical change in the life of Hungary, but also in the relationship of the countries of the world with Hungary. At the suggestion of Otto von Habsburg, Franco was the first to speak out in favour of the Hungarians. When the Soviet army occupied Hungary on November 4, 1956, Otto asked Ferenc Marosy by telephone to inform Franco of the situation and ask for help on his behalf. Franco convened a council of ministers that night, at which it was decided to send a volunteer army to Hungary. The Secretary of Defence resigned from his portfolio to become commander of the Spanish Aid Army. In a short time, 13,000 Spanish citizens volunteered, including two sons of Secretary of State Artajo, but the intervention was prevented, primarily by the US. The planes at the time would not have been able to get from Madrid to Budapest without landing, and neither Germany nor Austria, which was liberated in 1955, dared to risk allowing an intermediate landing. Franco would have been reluctant to bid defiance to the international community, thus eventually there was no military action. He had to limit himself to Humanitarian aid.

Madrid, Almudena Cemetery

Tombs of Lajos Mengele, Mares Blanche and Ferenc Marosy

(Photo: Embassy of Hungary in Madrid)

The Spanish economic situation did not allow the country to receive a large number of Hungarian refugees. In the UN data series from October 1 to October 31, 1957, it can be seen that at the end of October, there were only 17 Hungarians who had designated Spain as their destination. At the same time, Spanish society, with the support of the system, has set in motion. Organized by the church services and common prayers were held in cities. University students and their teachers took to the streets to assure Hungary of their solidarity. The papers presented in large numbers the moments of the outbreak and repression of the revolution. Spanish civil and charitable organizations and individuals opened charity accounts and collected food, medicine, bandages, blood, clothing, blankets, and anything that could help Hungarian refugees. On November 29, Real Madrid and Honvéd played a friendly football match, the proceeds of which were donated to charity. The Royal Embassy in Madrid also took part directly in the collection, from where the collected donations were transported by truck to Hungary and Austria. According to a summary from the archives of the Spanish Red Cross, the international organization donated goods in the worth of 600,000 pesetas.

A few years later, more Hungarian emigrants moved to Spain, including the legendary commander of the Corvin Lane, Gergely Pongrátz. Elisabeth Szél, dancer and writer who performed in London in the fall of 1956, was asked by her mother to move to Madrid. However, most people remember former Hungarian footballers. László Kubala was already the star of Barcelona at that time, after 1956 he helped the members of the Golden Team, Puskás, Kocsis and Czibor, to get a contract in Spain. József Tóth was a player of Eger, in the days of the revolution – at the age of 19 – he transported help to the Corvin Lane by truck. After the fall of the revolution, he preferred to emigrate to France, from where he received a contract to Atlético Madrid in the early 1960s, then became a respected scout of Real Madrid for decades and still lives in Madrid to this day.

Hungarians came to Spain in the 1950s through another channel as well. The College of St. James – established by Franco, – through the intervention of Otto von Habsburg and Ferenc Marosy, also gave Hungarians the opportunity to complete their university studies in Madrid after doing so for the Polish, Croatian and Slovak students.

The proclamation found by the Otto von Habsburg Foundation and the self-corrections made by Otto von Habsburg must be read in the context of the above. Although Franco’s anti-communist system was a dictatorship, it was a refuge for the Hungarians; that is why Otto von Habsburg’s words about him could have been so positive. Today, unfortunately, this could not be said in Spain without a person being immediately classified as a fascist; the current policy lacks an objective confrontation with the past that acknowledges historical facts and treats them in place.

Of course, everything was more complicated than this sketch at the time, and the role of Otto von Habsburg in it would also require a deeper historical analysis. For example, conspiracy theories that would have found the son of the last crowned Hungarian king conceivable even on the Spanish throne were not mentioned here. However, Otto von Habsburg was already more interested in European politics at the time than a possible role in a monarchy.

Note from the Press Department of the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (November 13, 1964) “Otto Habsburg is grateful to the Spanish lawyers for allowing the Hungarian Royal Embassy continue to operate in Madrid according to his instructions, which belongs to the rightful owner of the Hungarian crown.” (Source: Spanish General Archives of Administration, Alcala de Henares) |

Let’s end here with an anecdote to support how incapable today’s Spanish politics are in coping with its own XX. century history. When I arrived in Madrid, I found the ’56 memorial plaque, which was once erected and placed on the wall of the Toledo fortress by three young Hungarians, Gergely Pongrátz, József Tóth and Aurél Czilhert (embassy secretary of Ferenc Marosy) in the embassy garage. The Hungarian community held a memorial there every October. As the text of the sign expresses gratitude to the host country (meaning Franco’s Spain), it was not allowed to be restored after the fort was renovated. After a long deliberation, persuasion, with the help of an honest military commander who also took a personal risk by granting permission, the plaque returned, this time to the crypt of the fort, next to the tomb of the Civil War hero, General Moscardo. We did not invite Spanish officials, nor did we tell the press, but the Hungarian community was present in large numbers at the inauguration ceremony. József Tóth – the last living member of the three former financiers of the memorial plaque – also brought his grandchildren, and since then he has been visiting the plaque with them every October to commemorate his friends and comrades-in-arms.

Enikő Győri

Member of the European Parliament, former Ambassador of Hungary to Madrid and Rome

Translated by Zsófia Erdélyi