“We are not only creatures of the past but also creators of the future”—Balázs Orbán quoted John Lukacs in his welcoming speech. The Prime Minister’s Political Director stressed the significance of learning about the past, which is a moral obligation, especially for those who, like the students and teachers of the University, have chosen the service of the public as their vocation. “The next construction phase is underway to place the University in the international arena.” Their task is to represent the “Hungarian voice” and the appropriate strategy for tackling crises in the international discourse on the shifting world order. In the face of the ideological turmoil of Western civilisation and its obsolete theoretical constructs, there is no better example of the cultivation and transmission of universal, value-laden knowledge about the past than the legacy of John Lukacs, the politician stated.

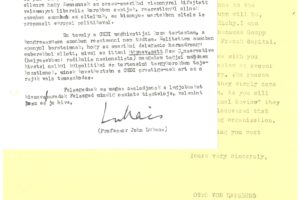

The Rector, Gergely Deli, introduced the newly established Institute, which was created by the merger of three former departments: the Institute for American Studies, the Institute for Strategic Studies and the Institute for Strategic Defence Research. Its mission is to preserve its namesake’s intellectual legacy, coordinate strategic research and promote a more active Hungarian participation in international academic life. Gergely Prőhle, Director of the Institute and the Otto von Habsburg Foundation, presented the audience with a selection of photographs of the John Lukacs Lounge, which he had actively participated in setting up at the University a few years ago: the historian’s belongings, his hand-made furniture, his medals, his sheet music and especially his books, sought to bring the multifaceted personality of the historian closer to the students. He also showed an exchange of letters between Otto von Habsburg and John Lukacs, which contains relevant insights into the diversity of the American conservative camp. On behalf of the family, Annemarie L. Cochrane, who lives overseas, greeted the assembled guests, honouring her father’s memory from a recording.

“Unreadable history is no history at all”—Pál Hatos reminded the audience of a historian’s prevailing responsibility. He implied, with the words of Johan Huizinga, that nowadays, due to the increasingly mechanised science industry, we are inundated with a plethora of historical writings, yet only very few of them are written in a meticulous, individual manner, the kind of which Lukacs has always striven to create. For him, respect for history was, essentially, a respect for freedom, and it was not by chance that he believed that knowledge in this area was not an individual but a collective achievement; to borrow Paul Ricoeur’s words, “History is an unpaid debt”.

“Historical consciousness means learning to pay attention to our own moral imagination and to perceive the memories of others, of things we lack first-hand experience of,”—Jeffrey Nelson echoed a fellow American historian in the introduction to his lecture. John Lukacs’s seminal work Historical Consciousness (1968) has aroused the interest of American conservative thinkers since its publication. Invoking the image of a literate historian, the Russell Kirk Centre Executive Director looked back to the beginnings in the 18th and 19th centuries. He sees the 20th-century “reincarnation” of the figure in the image and role of T. S. Eliot, George Orwell, G. K. Chesterton, Kirk and Lukacs, whose vocation was to defend “the old truths and rights”, continuity and constancy, against the temptations of progress and innovation. For Lukacs, historiography is an act of reconstruction, a moral deed which, freeing the Word from the grip of ideologies and positivism, can lead its reader to a new kind of humanism, a sort of wisdom, in literary form.

Recounting the creation and reception of Historical Consciousness, Hillsdale College professor Richard Gamble revealed that during the decade and a half of writing the book, Lukacs sought the opinions of only a few good friends—such as Russell Kirk, Dwight Macdonald, George Kennan and Owen Barfield—who repeatedly dissuaded him from abandoning his work, which he often felt was hopeless. He also drew inspiration from Werner Heisenberg, and after meeting him in 1962, he completely rewrote the manuscript, emphasising that it was an “autobiography of his principles”, or what he called “auto-history”. A perusal of their correspondence confirms that the book can be regarded as the author’s intellectual autobiography—until 1967 and the 1985 revised edition, supplemented by reflections such as The Confessions of an Original Sinner and The Last Rites. His mentioned works focus primarily on historical issues, but—as one perceptive reviewer has noted—they also offer multiple substantive philosophical, religious, sociological, psychological, semantic, biological and genetic reflections. In a letter to Macdonald in 1963, Lukacs defined his approach as post-scientific, and his book exploring the historicity of knowledge sought to contribute to a deepening of historical consciousness, in contrast to, for example, Spengler or Toynbee, who were merely working to broaden the horizons of historical knowledge. Gamble, who has long planned to pen a biography of Lukacs, sees the ambition of the author of The Historical Consciousness as returning man to the centre of the universe in the context of a new kind of humanism in today’s post-materialist, post-Cartesian, post-scientific world.

In her speech, Susan Hanssen placed Lukacs in a coordinate system defined by three fundamental trends in 20th-century American thought. According to these, the Hungarian historian arrived in the New World with the seventh wave of immigration, which enriched its scholarly life with the output of Central and Eastern European intellectuals, including Albert Einstein, Leo Strauss, Hannah Arendt, Jacques Maritain, Czesław Miłosz, Aleksandr Szolzsenyicin, Eric Voegelin, among others. In the fields of humanities, they renewed the continent’s thinking on natural law. They awakened interest in ancient political philosophy while working to preserve, not overthrow, the Christian liberal tradition of the West. The second current of ideas was the ‘third spring’ of the revival of English Catholicism, in which Christopher Dawson, Mortimer Adler and Graham Greene were Lukacs’s ‘fellow travellers’, many of whom not only achieved success in literature but also gained a place in academia. Thirdly, the speaker referred to the conservative heyday of the 1980s, which, thanks to the concerted policy of the Anglo-Saxon powers, brought about the fall of communism in 1990. Together, these influences shaped the image of Lukacs as a conservative Catholic intellectual, the professor at the University of Dallas believes.

Wilfred McClay, Professor at Hillsdale College, spoke about his personal experiences with the celebrant in a video message. He reminisced about their acquaintance when, as a history student at Johns Hopkins University, he was asked to review Lukacs’ book Outgrowing Democracy—A History of the United States in the Twentieth Century. After its publication, the author contacted him by letter and later extended his friendship to him. McClay recalled that Lukacs had described himself as a reactionary and idealised 19th-century bourgeoisie, arguing that it was feasible—or at least possible—to try to turn back the clock through historical consciousness. He learned from the Spanish-born American historian Georges Santayana that “any tradition is better than any reconstruction”.

In another video message, David Contosta, who honoured the professorship of John Lukacs, recounted the historian’s career and the magnitude of his oeuvre with a variety of personal stories, with particular emphasis on his two seminal volumes, Confessions of an Original Sinner and The End of the Twentieth Century and the End of the Modern Age. Lauding the work of his predecessor, he praised not only Lukacs’s greatness as a historian but also his linguistic qualities and ingenuity, and not least, his sense of humour.

Miklós M. Nagy, the Editor-in-Chief of Helikon Publishing House, likewise knew Lukacs well and translated many of his books into Hungarian. In his presentation, he proved that the historian (also) had outstanding penmanship, and at the same time, he sought to explain why, despite this, not as many people in Hungary read his books as he deserved. Nevertheless, his writing has it all: a penchant for word magic, meticulous observation and description of details, nuanced characterisation and aphoristic style, all of which are even more impressive in Hungarian than in English. Perhaps it is the genre and the political unclassifiability—a fundamentally likeable phenomenon that can be easily explained by the personality and biography of the author—that lies behind this observation, pondered M. Nagy.

During the commemorative meeting, the participants also engaged in round-table discussions with the Hungarian guests and reflected on Lukacs’ thoughts. The panel, chaired by Ferenc Horkay Hörcher, focused on the historian’s appreciation of the role of personality in shaping history. In this context, they explored Lukacs’ assessment of 20th-century US history, particularly the performance of certain presidents and parties. They concluded that if they had to name a single of his ‘heroes’, it would undoubtedly be Winston Churchill, as he embodied both the characteristics of the aristocratic politician and the intellectual statesman. According to Associate Professor Máté Botos (PPCU), Lukacs valued the British politician’s vision and Ronald Reagan’s sincerity while sharply criticising his populist statements. However, regarding the upcoming US presidential elections, Máté Gali (MCC School of Social Sciences and History) did not think it likely that Lukacs would vote for the Democratic president if he could.

The last thematic section of the event, “The Mavericks of History: John Lukacs and George F. Kennan”, was introduced by philosopher Miklós Pogrányi Lovas. The Senior Analyst at the Centre for Fundamental Rights defined Soviet politics, fundamental to both historians, as the culmination of Marxist ideology, Russian spirituality and progressive thought. In his presentation, Tibor Glant, a professor at the University of Debrecen, described the members of the American historical community who emigrated from Hungary alongside Lukacs. The list of names is considerable—István Deák, Péter Sugár, István Várdy, Dénes Sinor, Károly Gáti, Péter Pásztor and others—but beyond the community of origin, the differing emphases of their careers are also clear. Bence Kocsev, a colleague of our Foundation, based on the correspondence of George F. Kennan and John Lukacs, asked his interlocutors to what extent the two men’s status as outsiders of their professional guilds was a consciously assumed or forced condition. As they recalled, Lukacs repeatedly expressed his conviction that a humanist could not be specialised but must be able to navigate a broad spectrum of disciplines (the most intense example of this can be found in his decade-long correspondence with Werner Heisenberg). He was always careful not to be pigeonholed into a single intellectual circle, trend or school—and not infrequently played up his role. The roundtable discussion established that his Hungarianness, his Central Europeanism, his Europeanness and, within America, his local identity linked to Philadelphia shaped the particular tone, world and historical vision that defined him throughout his career.

Máté Dömötör performed the favourite melodies of John Lukacs on piano.

Photographs by Zoltán Szabó