It is a well-known fact that Otto von Habsburg was a deeply religious Catholic. Throughout his childhood years, a chapel was established in all the places the family lived in exile. He listened to Mass every day, served and took communion many times. His Christian faith remained decisive for him as an adult and throughout permeated his public life. He was consciously looking for events that carried the opportunity to make new friendships in addition to spiritual reset. It is no coincidence that in 1952 he and his wife attended the 35th International Eucharistic Congress in Barcelona.

Otto von Habsburg and his brothers, Felix and Robert as altar servers (1921)

Source: HOAL I-5-a 4

The Catalan capital organized the event 14 years after the 1938 International Eucharistic Congress in Budapest, as the meeting scheduled for 1940 in Nice was exacerbated by World War II. From 1938, Spain sought to win the right to host the highly prestigious Catholic meeting, which was originally scheduled for 1944. The Archbishop of Toledo, Isidro Gomá y Tomás, also came to the Budapest Congress to help the preparations. Bearing political considerations in mind Rome also supported this endeavour after the war. Vatican diplomacy negotiated a new concordat with the Spanish government in the early 1950s and sought to bring the United States and Spain closer together. In the increasingly tense international climate of the Cold War, a greater understanding of the Franco regime seemed justified, and Spain’s deep-rooted Catholic tradition also spoke in favour. The chances of the Barcelona site were enhanced by the city’s good accessibility, as well as its gloomy recent history, as it was suitable, through the suffering it experienced during the Civil War, to be a symbol of a new beginning, a hope of resurrection.

The central theme of the 35th International Eucharistic Congress was peace. The decision was made five years after World War II, as a result of Cold War developments – the threat of nuclear war and communist propaganda (eg the Stockholm Peace Call in 1950). XII. Pope Pius observed with particular concern the persecution of Christians in the Eastern Bloc and the spread of Marxist ideas. In this context, the Holy Father considered it important that Catholics, especially Europeans, be spiritually armed against Communism. It is no coincidence then, that during the Congress, the subject of peace was examined from four main perspectives: the Eucharist and family peace, the Eucharist and individual and social peace, the Eucharist and international peace, and the Eucharist and ecclesiastical peace.

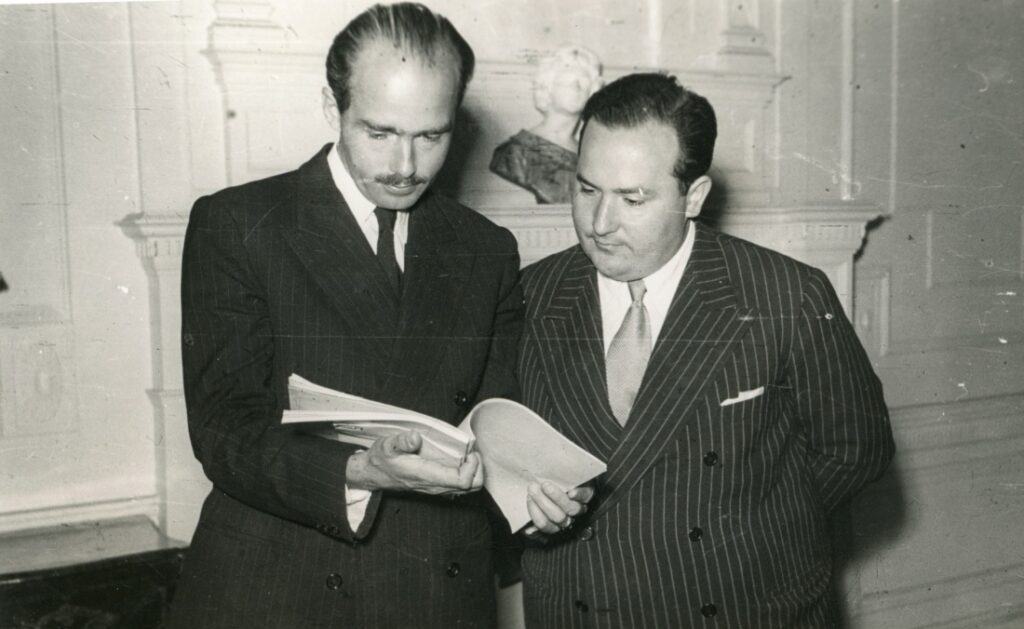

Alberto Martin Artajo, Achduchess Adelheid and Otto von Habsburg (1952)

Source: HOAL I-5-a 5-4

In May 1938, just a few months after the Anschluss, the former Crown Prince was unable to travel to Budapest as he was exiled. Thus, for the first time, it was not until 1952 that he had the opportunity to participate in the International Eucharistic Congress. Given all this, it is not surprising that Otto von Habsburg, who had close emotional ties to Spain, enthusiastically signalled his intention to attend the Barcelona event.

The Spanish trip of Otto, his wife Archduchess Regina and his sister Archduchess Adelheid, was organized by Ferenc Marosy, the Hungarian royal ambassador to Madrid, informally recognized by the Franco regime. (The diplomat was assisted in his work by Alfréd Egán, a former Hungarian consul in Barcelona.) Marosy, who also played an important role in setting up the official Hungarian delegation, agreed with Otto von Habsburg. Following several exchanges of letters, a group of mostly ecclesiastical people living in Western political emigration came together – led by Roman Prelate Joseph Zagon and former Ambassador to Vatican City, Maltese Knight Gábor Apor. This group was recognized by the organizers as an official delegation. At his own request, Otto von Habsburg was not on the list of the Hungarian delegation or any other nation.

Marosy tried to make the son of the last ruler of the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy one of the most distinguished personalities to appear at the event. The diplomat informed Otto von Habsburg that he could also attend the highest-level reception in honor of Cardinal Fedico Redes Tedeschini, the papal legate traveling to the Eucharistic Congress. During the congress, Spanish national radio provided the former Crown Prince with a few minutes to speak.

Otto von Habsburg and Alfredo Sanchez Bella (1952)

Source: HOAL, Photo Collection

Otto von Habsburg was already a well-known personality in Spain at that time. In 1949 he had a personal meeting with General Franco, who showed particular appreciation towards the head of the historical family. Through his good relations with France, Otto played a mediating role in improving French-Spanish relations, which became very tense after 1948. Alberto Martin Artajo, the foreign minister of the Franco regime and a member of the Spanish leadership of the Actio Catholica, also sympathized with Otto von Habsburg. It is no coincidence that in 1952 he was treated as a privileged guest by the Spanish authorities. As early as March of 1952, the Madrid Foreign Ministry instructed the governor of Barcelona to find suitable accommodation for Otto. They booked a room at the modern Arycasa Hotel in the center of the Catalan capital, which was completed for the Eucharistic Congress.

It was here that he was introduced to Alfredo Sanchez Bella, director of the Spanish Cultural Institute, by Jean Violet, a close associate of Antoine Pinay, French prime minister at the time, and an agent of the French secret services. Bella was impressed by the fact that the son of the last ruler of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy took part in the marches organized during the congress as a cross-carrier, united among the people. This meeting was also decisive for Otto, as Alferdo Sanchez Bella became the one with whom, as a result of discussions, lectures and experiences during the congress, he established the organization Centro Europeo de Documentación e Información (CEDI) a few months later. The main objectives of the initiative were to bring together various Christian and conservative organizations, mainly in Western Europe, to gather information, combat communism and preserve Christian European values and, last but not least, to promote the process of European integration.

CEDI meeting, Santander, Spain (1952)

Source: HOAL, Photo Collection

It can be said, then, that the 1952 International Eucharistic Congress was a milestone in Otto von Habsburg’s commitment to the protection of Christian Europe. In September, at the meeting in Santander, which founded CEDI, he gave the closing remarks, stressing:

“Sometimes, like the Jewish people of the Old Testament, we think of everything in an overly earthy way. They were waiting for the Messiah as a king in the political sense, and we believe that the empire should be expressed in the forms known in history. In reality, however, the Christian empire is more the spirit of solidarity, the Pax Christi thought, the practical implementation of gospel principles, the cooperation of free peoples who acknowledge the Kingdom of Christ. […]

In recent days, we have studied the nature and vocation of Europe from a variety of perspectives. And we have all come to the conclusion that the European idea cannot be separated from Christianity. Europe must understand that it is a Christian continent, that its vocation is to bear witness to the divine truths on earth.”

During the grandiose Congress in Barcelona, where more than 300,000 pilgrims from 64 countries were present and the number of attendees at the final Mass was estimated at 1 million, Otto met many Spanish and non-Spanish politicians, public and church figures.

Posters of the Eucharistic Congresses in Barcelona and Munich

Source: HOAL, Collection

Otto von Habsburg took part once again in the International Eucharistic Congress eight years later, in the summer of 1960 – this time in Munich. Due to its geographical proximity to his residence, Pöcking, his wife and children, his mother, Queen Zita, and several of his siblings were also present at the event. As in Barcelona, the meetings at the International Eucharistic Congress in Munich became crucial in Otto’s life, as he spoke here for the first time in person with Julius Raab, the Chancellor of Austria, on 7 August 1960.

Otto wanted to settle his relationship with Vienna after the Austrian state treaty concluded in 1955. However, the process has dragged on for many years and has caused serious tensions in Austrian domestic politics. Otto von Habsburg has been unjustifiably slandered and attacked, mainly by the Austrian Social Democratic Party (SPÖ), for example by seeking to repatriate huge fortunes from his homeland and forcing anti-democratic measures on his return. In this context, a personal discussion between the former Crown Prince and the People’s Party (ÖVP) Chancellor Raab was particularly important. The meeting was organized by German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer at the Munich Congress. At a meeting at the Jahreszeiten Hotel, Raab made it clear to Otto that if he wanted to return to Austria, he would first have to make a declaration of resignation from the throne. Although it still took many years for the legal status of the son of the last Austrian emperor to be settled, the Munich meeting proved to be key, according to Otto von Habsburg’s later recollection.

Otto von Habsburg and his family in München at the Eucharistic Congress in 1960

(l-r: Otto, Regina, Queen Zita, Adelheid, Elisabeth)

Source: HOAL I-5-a 6-15

The two International Eucharistic Congresses he attended had a significant impact on the life of the former Crown Prince: spiritually through the experience of the transcendent and in a socio-political aspect through human encounters. In 1952 because of the idea of a “Christian Europe,” and in 1960 for his relationship with his homeland. In both cases, the International Eucharistic Congress reaffirmed him in his Catholic faith, as well as in his European and public moral commitment and the fruits of this were tangible throughout his later life.

Gergely Fejérdy