Presentation of the Bugatti EB110 in Paris (14 September 1994)

Source: HOAL I-5-b 9-3

A significant part of our foundation’s photo collection consists of images of Otto von Habsburg with a car, in a car or in the company of some other means of transportation. This is no accident, as being a very busy person, he travelled a lot, on water and in the air, but mostly on land. He knew well that a good car was not just a means of locomotion, but much more than that. The photographs show that he appreciated high-quality, aesthetic vehicles – from the reliable family station wagon to vehicles used for various excursions to the elegant but not ostentatious automobiles used for work. No wonder he also had a relationship with Bugatti, an elite in the automotive industry.

The Dream of Ettore Bugatti

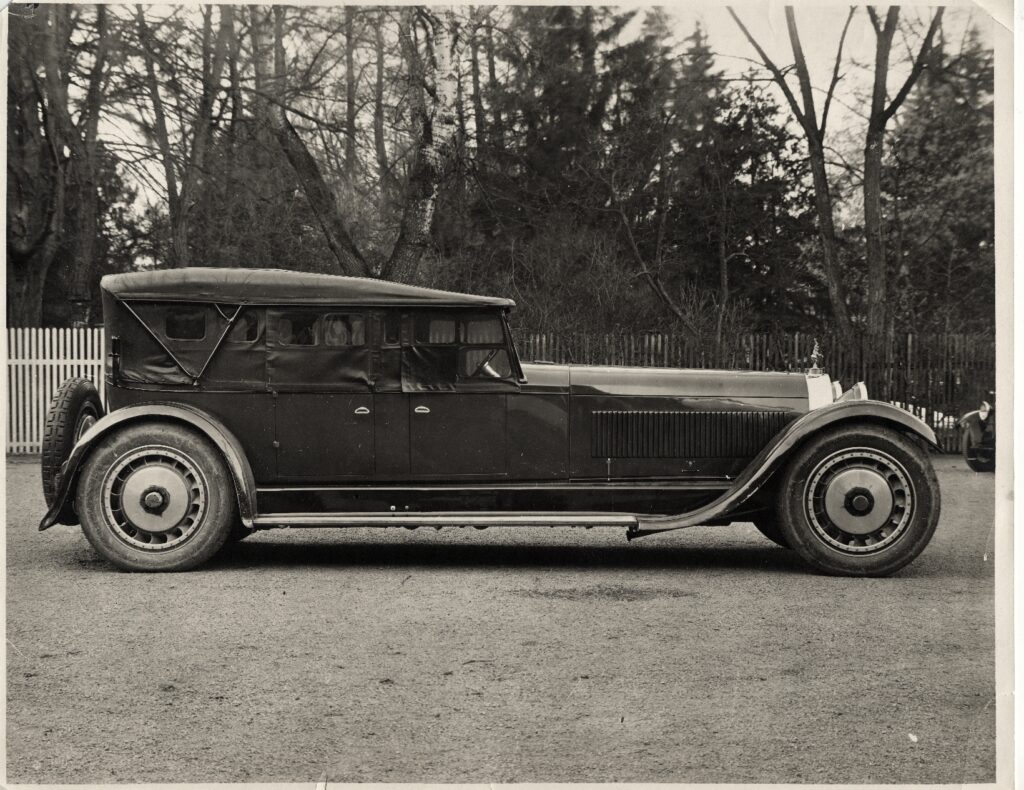

Bugatti, a high-end automotive company, was founded in 1909 by Italian-born designer Ettore Bugatti. Entrepreneur, engineer, car racer Ettore was born in 1881 to a family of artists in Milan and then designed his first car at the age of 17, with which he won first prize at an international exhibition in Milan. He was then invited by Baron Eugene De Dietrich of Lorraine to design a car for his factory in Niederbronn, Alsace, then Germany, part of France from 1918. Gradually climbing upward, Bugatti was soon able to set up his own car factory in Molsheim near Strasbourg. The company had been making the world’s most impressive and fastest cars for thirty years, winning podium finishes at various races. The Bugatti name was synonymous with quality and luxury, with the Bugatti Type 41 Royale or Bugatti 57sc Atlantic being considered by many to be the most beautiful cars ever made.

Prototype of Bugatti’s Type 41 Royale (1926)

Source: Bugatti newsroom

Ettore Bugatti’s racing and luxury cars were among the most outstanding vehicles of the period between the two world wars in Hungary as well. The first record of a Bugatti car is related to the 1920 Svábhegy Race, shortly after which the first official Bugatti show room opened in Budapest. Owning a Bugatti was a very exclusive thing at that time already, so it is no wonder that rather aristocrats could afford it. For example, Prince Antal Eszterházy or Count Tivadar Zichy, who also used three different Bugattis for a short time. During World War II, the national vehicle fleet suffered significant losses, by 1950 there was only one Bugatti left, and the brand had actually disappeared from Hungary by the 1960s.

Otto von Habsburg also met Ettore Bugatti in person in Belgium in the late 1930s. He thought back to meeting and talking to him as unforgettable memories, as for those interested in motorsports, the name Bugatti had clear significance. He later recounted that he was no less impressed by Ettore Bugatti’s personality, calling him a man who was simply surrounded by an aura of genius.

In 1939, Ettore Bugatti’s son, Jean, who was also involved in managing the company, suffered a fatal car accident while testing. The company could not recover from this loss and the devastation of World War II. Ettore Bugatti died in 1947, and his company ceased production of road cars in 1952. The company did not go out of business but switched completely to manufacturing aircraft parts in 1963 as a member of the Hispano-Suiza and then in 1968 of the French Snecma group.

Ettore Bugatti with his son, Jean sitting in the car, before the French Grand Prix

Source: Roadster, Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images

The Bugatti-Revival

The idea to revive the Bugatti name was born in the summer of 1986, when some of Lamborghini’s then and former employees brainstormed about creating an exceptional sports car. There was an engineer, a designer, a development and branding specialist, the only thing they were missing was funding. This is how Italian businessman, investor Romano Artioli came into the picture, who was also interested in designing a unique sports car. Artioli was a passionate car collector and, as one of Europe’s most important Ferrari dealers, earned a respectable income by exporting Ferraris to Germany and importing Suzukis to Italy. At the end of the eighties, the segment of supercars – that is, high-performance, luxury sports cars – flourished, so it was possible to jump into the business in the hope of significant profits. Negotiations soon began over the rights to the Bugatti name – which was a rather delicate endeavour, as the French, the right holder, did not want anyone to misuse the brand name. Finally, in October 1987, it was announced that the Bugatti name and intellectual property rights had been transferred to a group of Italian businessmen, and Luxembourg-based Bugatti International was formed under the leadership of Romano Artioli.

The dream of those behind the turnaround was to build the best supercar, using the most advanced, state-of-the-art technology available. Achieving this required efficient and easily accessible infrastructure, which would not have been easy to solve at Bugatti’s original home in Molsheim, Alsace, but in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy was everything given to succeed. The area around Modena is rightly called the “Silicon Valley of Supercars”, with the headquarters of renowned companies such as Ferrari, Lamborghini, Maserati or DeTomaso. Thus, taking into account the needs of future workers, the site for the construction of the factory and headquarters was chosen in the town of Campogalliano near Modena, with a population of about 9,000. The production of the best car in the world required the best designers and engineers, and the most serious top-notch engineers and masters working for Formula 1 teams were lured to the company. Which had not been so difficult, thanks to the still very exclusive chime of the Bugatti name.

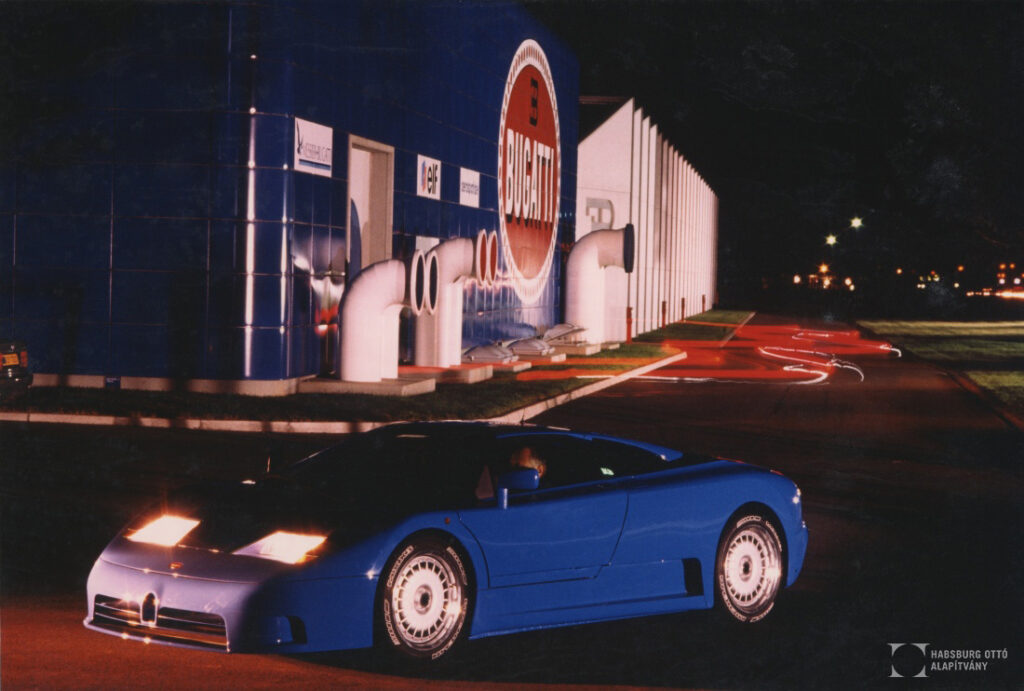

The prototype of the new model in front of the Blue Factory (1991)

Source: HOAL I-5-b 9-3

During the design process of the building, they tried to create the “Bugatti of the factories”, an avant-garde and modern complex equipped with the latest technology, which is as much a sight as the car itself. The building, “La fabbrica blu” (The Blue Factory), opened its doors on September 15, 1990, on Ettore Bugatti’s 109th birthday, after nearly three years of construction. At the inauguration ceremony, the Archbishop of Modena performed the ceremony in the presence of the cream of the Italian automotive industry and also in the presence of Otto von Habsburg.

Imperial Relations

Otto von Habsburg has been interested in cars all his life. His father, King Charles IV, owned an Austrian-made Gräf & Stift, but what Otto sat in for the first time in his life as a small child was a Spanish car, a Hispano-Suiza. When he became an adult, he and his family were living in Belgium, and with the help of a professional driver he learned to drive in a Ford. At that time, everyone who had reached the age of 18 was free to drive without passing an exam. Later, although he preferred to sit in a Mercedes, he also had a Magomobile made in Hungary in 1926 by the Hungarian General Machine Factory (MÁG). This vehicle was unfortunately destroyed during the Spanish Civil War (or World War II).

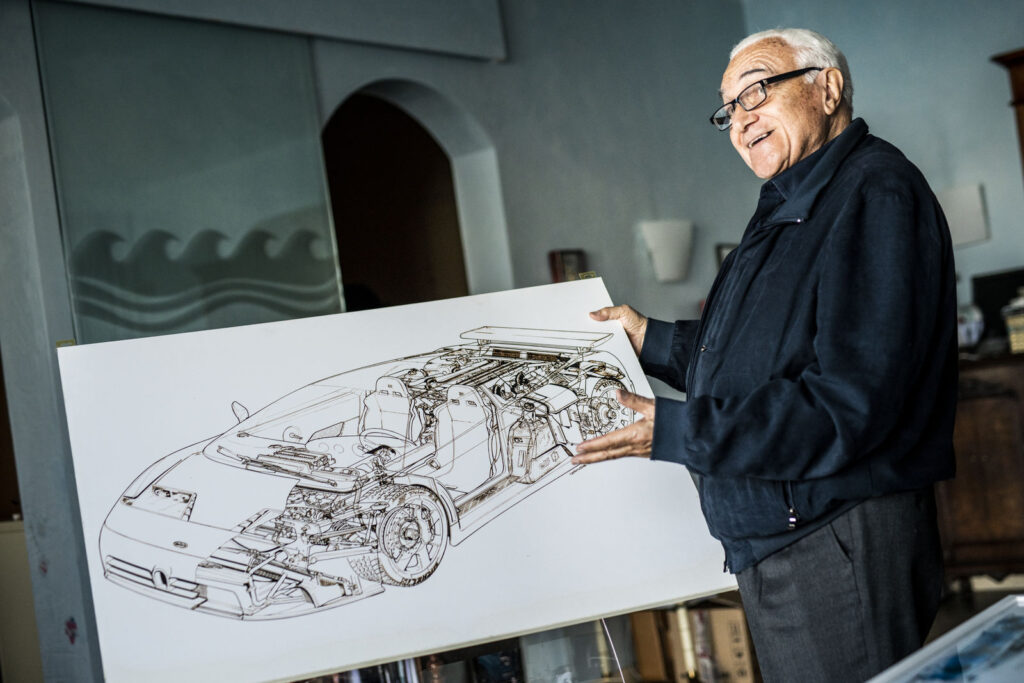

Otto actually got involved in Bugatti’s revived car production by chance. In his memoir, Romano Artioli recalled that in 1988 he read the news in a Bologna newspaper that Otto von Habsburg would soon be coming to Italy to support MEP Gustavo Selva’s campaign, visiting Bologna, Verona and Padua, among others. Selva confirmed the news to Artioli and complained that he did not know how to organize the escort service of the campaign tour, as “the emperor must be accompanied on an equal footing with a head of state”, but Italian road patrols were not available in this case. Artioli offered to make the company’s private jet available during the trip. Selva was soon pleased to inform him that “the emperor was happy to accept the offer”. Romano Artioli grew up in Bolzano, the seat of South Tyrol, in his eyes Otto, “the emperor”, was the spiritual and charismatic leader of his homeland. He recalled their joint flight the most beautiful journey of his life, during which Otto received with particular interest the news that Italian, German and French engineers were working together, giving a perfect example of how mutual knowledge and a common goal could lay the foundations for ideal integration.

Romano Artioli

Source: Bugatti newsroom

On 15 September 1989 – Ettore Bugatti’s 108th birthday – Otto von Habsburg attended the inauguration of the Ettore Bugatti Cultural Center in Ora, Bolzano as Chairman of the Bugatti International Honorary Committee. A 1930 Bugatti T49 took Otto to the venue, where traditional Tyrolean Shooters (Die Tiroler Schützen) were waiting in a line, and the military band played the Radetzky Marsh. (As it turned out later, a local delegation set up in a hurry went to Strasbourg before the event, advising Otto not to take part in the event because it was organized by Italians. Refusing to waste time listening to such nonsense, he asked the delegation to go home.) The event was a success, in his speech he praised Ettore Bugatti’s work, speaking of a perfect synthesis of technology and art combining human progress and environmental protection. He presented the Europeanness of the Italian designer, who designed for France and, who knew, therefore, that there was no contradiction between being loyal to his homeland and believing in the broader European conception, and that the complete absurdity of the fraternal wars, i.e., the First and Second World Wars happened because of destructive nationalism. In his speech, Otto also referred to Hungary and István Széchenyi: “The great Széchenyi said to his homeland, Hungary, more than a hundred years ago: “Hungary was not, but will be.” We also hear this sentence from Budapest today, where after decades of totalitarian oppression the era of freedom begins. In the case of Europe, I would like to change the sentence a little bit, because Europe was always something grandiose, the most beautiful thing that humanity has been able to create so far.

In this sense, my formula for tomorrow is: “Europe was, thus will be.”«”

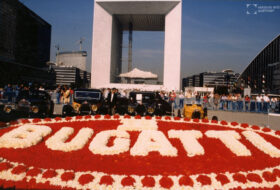

Unveiling in Paris

In the spring of 1991, the factory in Campogalliano was still working feverishly on the technical details of the new model, preparations for the presenting event were already in full swing in Paris and Alsace. At the Bugatti, the new car was given the EB110 model name, in honor of the company’s namesake on the one hand, and in commemoration of Ettore Bugatti’s 110th birthday on the other. One year after the factory was founded – again, adjusting the date to the birthday – they could already present the model.

The grandiose event took place on 14 September 1991 on the Parvis de la Défense in Paris. According to the script, the exhibition of classic Bugatti models formed a horseshoe shape in the square, with the prototype of the EB110 to be presented hidden under a blue veil in the middle. Bugatti paid for all the employees of the company for their travel and participation at the event, which was attended by roughly 5,000 guests and journalists. The solemn unveiling took place after Otto von Habsburg’s welcome speech in French. The gala event was hosted by French film live legend Alain Delon, who, along with Artioli’s wife, Renata Kettmeir, head of Bugatti’s luxury goods subsidiary, pulled the veil off the EB110.

Alain Delon was previously a passionate Bugatti collector. Ettore’s brother, Rembrandt (!) Bugatti, carried on the traditions of the artist family and became a sculptor, making bronze sculptures depicting mainly wild animals. During World War I, he volunteered for an ambulance job at a military hospital in Antwerp. This experience had a profound effect on him, as a result of which he also struggled with depression, eventually committing suicide in 1916, at the age of 31 years. The story of Rembrandt Bugatti’s early death touched Alain Delon, who put together a unique collection of his work. Ettore made the Dancing Elephant – sculptured by his brother – the mascot of the Bugatti Royale when he had it mounted on its radiator. Presumably, this connection prompted the management of the Bugatti company to ask the acting legend to present a new model of the company that is just being revived.

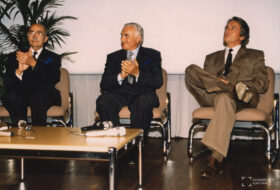

Otto von Habsburg, Alain Delon and Romano Artioli (Paris, 14 September 1994)

Source: HOAL I-5-b 9-3

After the show, three EB110s and their entourage marched from the Défense Quarter via the Champs-Élysées to Concorde Square, where the palace, built by King Louis XV, is still the building of the Automobile Club de France. For the guests, however, this was not the end of the event. In the evening, a gala dinner was organized in an unparalleled location: in the “Orangerie” (Palm House) of the Palace of Versailles, where 1,800 guests could enjoy the majesty of the place and the hospitality of the Bugatti company under the arches. The next day – on the birthday anniversary – two EB110 prototypes traveled to Molsheim to pay homage to Bugatti’s intellectual home. The press conference was held at the Schlumpf Collection in Mulhouse, where the new model was exhibited among 150 classic Bugatti.

The photo album presented here, managed by our Foundation, was sent to Otto von Habsburg by Romano Artioli in October 1991, accompanied by a thank-you-letter. Interestingly, already then, he portrayed the company as a small dwarf in the grip of giants, and this narrative reappears years later. At that time, however, he wrote these words still in an optimistic tone, with an enthusiasm that helps overcome difficulties. The album includes 14 photos of the event, the press conference and the gala dinner. Artioli and Otto then corresponded for some time, first regularly, then at a thinning pace. These letters were written mainly in German, but in some cases also in Italian and French, Artioli always worded with the utmost respect, calling the recipient “Your Majesty”.

The photoalbum of the introductory event of Bugatti EB110

Source: HOAL I-5-b 9-3

The large-scale presentation of the Bugatti EB110 was enthusiastically followed by the contemporary trade press. The car soon became iconic and was tested by hundreds of journalists around the world, and potential buyers began to take an interest. To maintain exclusivity, customer candidates were always monitored by company people before sale.

In 1992, Bugatti released an even lighter and more powerful EB110 model, which was given the SuperSport model name. Somewhat unexpectedly, this type received a particularly positive publicity in 1994. German car magazine Auto Motor und Sport has published a supercar comparison with F1 champion Michael Schumacher at the wheel, featuring a Ferrari F40, a JaguarXJ220, a Porsche Turbo, a Lamborghini Diablo and a Bugatti EB110 SS. Schumacher liked Bugatti so much that he immediately ordered one for himself. The handover of the car, of course, brought special media attention to the type. In 2003, Schumacher sold and then allegedly repurchased the EB110. His car reappeared in July 2021 when it was seen somewhat damaged in a garage full of luxury cars during the major floods in Germany.

Michael Schumacher takes over his Bugatti at the Campogalliano centre

Source: The Bugatti EB110 Registry

The technical parameters of the Bugatti EB110 are also outstanding. The car is powered by a 60-valve, quad-turbo V12 engine. It has a nominal 3.5-liter engine of 3499 cm³, 560 horsepower on the GT, 610 horsepower on the SuperSport. All-wheel drive, carbon frame and only 1550 kg. It reaches a speed of 100 km/h in 3.4 seconds and its top speed is 350 km/h. All in all, it is characterized by advanced technology and easy handling. The EB110 soon became a legend for its performance, the pedigree of its star developers, but also because of the brevity of its history.

In the summer of 1993, Bugatti introduced the EB110 in Japan. To build the relationship, Artioli had previously asked Otto for help and approval, who was happy to help. A package of four EB110s and one – future model – EB112 concept was delivered to Tokyo. The Japanese show was judged a success after all four 110s sold out, but that was no longer enough for overall success.

The Fracture

In 1995, dark clouds began to gather in the skies of the company’s financial stability. In order to maintain solvency, 150 cars would have had to be sold per year, but after four years, a total of only 139 cars were sold. Unpaid bills accumulated rapidly, losses increased, and by September 1995, bankruptcy seemed inevitable. The reasons were quite varied. Romano Artioli later stated that what was strange to him was the sudden drop in orders and the sudden rejection of parts suppliers to further cooperate with Bugatti. The process went so quickly and decisively that he said the descent was accelerated by sabotage. In addition, of course, production itself was far from efficient, which may have been one of the main causes of financial problems. Since everything was handmade, almost as in a manufactory, the process was very slow, producing an EB110 every 54 days – as opposed to Ferrari, which produced more than one car a day. Some also cite the general decline in supercar sales in the early 1990s, while others the shortcomings in the company’s financial management. Then there are the rumours about Bugatti’s mafia relations, which – even if their reality is doubtful – certainly did no good to the company’s reputation. The introduction of the latest models from competing manufacturers (McLaren F1 and Jaguar XJ220) just a few months after Bugatti may also have played a role in pushing the EB110 into the background. Like the Bugatti, these were excellent cars, and both immediately overturned the title of “fastest production car” set up by the EB110. And perhaps more importantly, they enjoyed the support of the big automakers – Jaguar for Ford and McLaren for BMW – while there was no such caring “big brother” behind Bugatti.

Between 1991 and 1995, 139 of the EB110 were officially made, of which thirty-three were SuperSport models. Not only have the cars retained their value, but they are constantly rising. The original price of the EB110 GT was around 200,000 French francs at that time (roughly HUF 107 million at current prices). Today prices typically range from $700,000 to 1,000,000 (HUF 208-300 million). In the case of the rarer SuperSport, the numbers are even higher, in 2015 a 1995 lemon-yellow model sold for £ 627,200 (HUF 281 million) at Sotheby’s, and in 2019 the same model sold for € 2 million (HUF 702 million) at an auction.

Bugatti EB110

Source: HOAL I-5-b 9-3

The Second 110

The EB110 was an engineering masterpiece in vain. It was unsuccessful in sales, and is often referred to today as the “forgotten supercar.” It is a rather paradoxical situation: it failed, but it was also a success. The company went bankrupt, but it served the brand fairly, and no doubt such a car was created that Ettore Bugatti would have liked to have given his name to. Otto von Habsburg formulated the reason for the success in the cooperation of European nations: in the combination of German precision, French production efficiency, and Italian elegance. In his view, progress is not in state-sized giants, but in the small independent businesses that are truly mobile and believe in individual responsibility and performance.

Yet the name Bugatti was acquired in 1998 by a giant company, the Volkswagen Group, which relaunched the brand as Bugatti Automobiles S.A.S. and created perhaps the world’s best-known Bugatti, the Veyron. Additionally, in 2019, the Bugatti Centodieci, which means “one hundred and ten” in English, was introduced, and it is actually a further developed version of the classic EB110: a tribute to the model that took the Bugatti back to the top of the automotive industry. However, VW itself admitted that the model was unprofitable, with only a fraction of the costs recovered from the sale of the small series models.

In the summer of 2021, the Croatian businessman Mate Rimac, who gained reputation for his electric supercars, became the owner of the Bugatti. Thus, the French company – founded by an Italian designer on German soil, later revived by an Italian businessman from a predominantly German-speaking province by a presentation in the French capital attended by the last Austro-Hungarian Crown Prince – now moves to the most recently joined EU member state, Croatia. For the centre of the newly formed Bugatti-Rimac will be in Zagreb.

Szilveszter Dékány