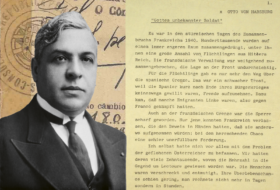

Photo: Otto von Habsburg at the exhibition opening on the occasion of the Márai Centenary in the writer’s home (Kosice, 11 April 2000)

|

San Diego, 20 November 1987[1] Your Royal Highness, Not many people left who can say that they were there on one November[2] morning in 1916 at the so-called Uri Street in the Castle District of Buda and saw the court chase drive through the line of revellers with the royal couple arriving from the coronation ceremony. But I was there as a sixteen-year-old teenager, and in the vehicle, I saw the crowned Hungarian King with the Queen by his side, and I saw a boy (in an attila [a white Hungarian short coat], I believe) leaning on the knee of the lovely young Queen; and at the sight of him the crowd shouted loudly, “The heir to the throne.” The carriage drove away, but the memory persisted. This was one of the last great moments when many hoped that the royal couple would be able to find a way out of the horrendous quagmire of war. And many of us regarded the child with hope, trusting that he would have the means and the strength to fulfil his calling. It was not to be, but the memory remained strong and vivid. Now, when Your Majesty is celebrating his 75th birthday, as an old witness, I reminiscence about many things, and I shall not fail to wish Your Majesty bodily and spiritual vigour for a long time to come, Yours sincerely, Sándor Márai [3] |

1987 brings another tragedy for the Hungarian writer, who had chosen emigration four decades earlier: after losing his faithful companion Lola in the previous January, their 46-year-old foster son János dies unexpectedly in the spring. He spends his days in complete solitude, with dwindling physical strength and a fading spirit. He seldom writes in his diary, no longer writes books, only reads lines and short passages, and has not listened to music for years. “I am cold. Summer is over, which was no summer; life is over, which in the end has brought nothing but grotesque old age and absurd death,” he ruefully confesses.[4]

In this state, memories become more precious. Especially the anniversaries and birthdays. On his own – which he has been marking with Roman numerals for some time – he makes a brief summary every year; on his name day, he takes a “roll-call” to determine who is still alive among the participants of the last Sándor (Alexander) Day they spent together in 1944. But he also commemorates Lola each year, their child, Kristóf, who died at a few months old, and the date of their departure from Hungary.

His lines to Otto von Habsburg were not prompted by a sense of nostalgia for the Monarchy. Márai does not primarily look back on the greatness of the political system and the impressive economic achievements of the dualist state but laments the cultural atmosphere of the time and the lack of an outlook on life and a lifestyle worthy of human beings in the private and public circles. Among the dozen or so documents of his exchange of letters with the former Crown Prince between 1977 and 1988, largely confined to birthday celebrations and acknowledgements of the volumes they sent each other, this is the only one in which he refers to the “Bygone Empire”, on the pretext of their one – and only – personal encounter.

In his diary kept from 1943 onwards, he dwells longer on Otto’s person only once.[5] The entry is from 1979, at the end of their stay in Salerno: “Habsburg Ottó könyve: Jalta, és ami utána történt (the book of Otto von Habsburg: Yalta and what happened afterwards)[6] Among European role-players, this one remaining Habsburg is a rare person who deserves credit. His erudition, cosmopolitanism, courage in exposing and speaking out against the treachery of Yalta, his refined taste and magnanimous tact, all combined, are a rare phenomenon. I agree with almost everything that he rejects and denies: communism, the tainted pseudo-democracy… However, then comes the threshold where the reader halts, when he not only says what he does not want but also states what he does want: a Christian Europe. Here, the reader coughs and closes the book. No wonder that a Habsburg is religious; his background, upbringing, everything puts him on the clerical side. Nothing to be surprised that such an exceptionally well-educated and astute statesman [wanted] a European confederation – which is being hammered out, and which is the last hope that the whole of Europe will not become some sort of Finnified Russian colony (it will be anyways, even if the Soviet empire abandons communism, because this enormous power, armed to the teeth with imperialism, is now imposing its weight on the loosely knit bundle of nation-states in Europe). So what is the »Christian Europe«? When was Europe truly Europe – in the Faustian sense: a searching, exploratory, dialectical Europe?” [7] – Márai wonders to himself, reflecting back on one and a half thousand years of history with a sombre assessment.

His pessimism becomes understandable in the light of his fate. By this time, the writer followed day-to-day political events with waning interest. Therefore, he paid no attention to the European Parliament elections of that year, which fundamentally changed the future of the continent and marked the beginning of a new phase in Otto von Habsburg’s political career. Márai was already bidding farewell to the Old World: “My relationship with Europe, now, as the moment of perhaps final departure approaches: not »disappointment«, worse. Indifference.”[8]

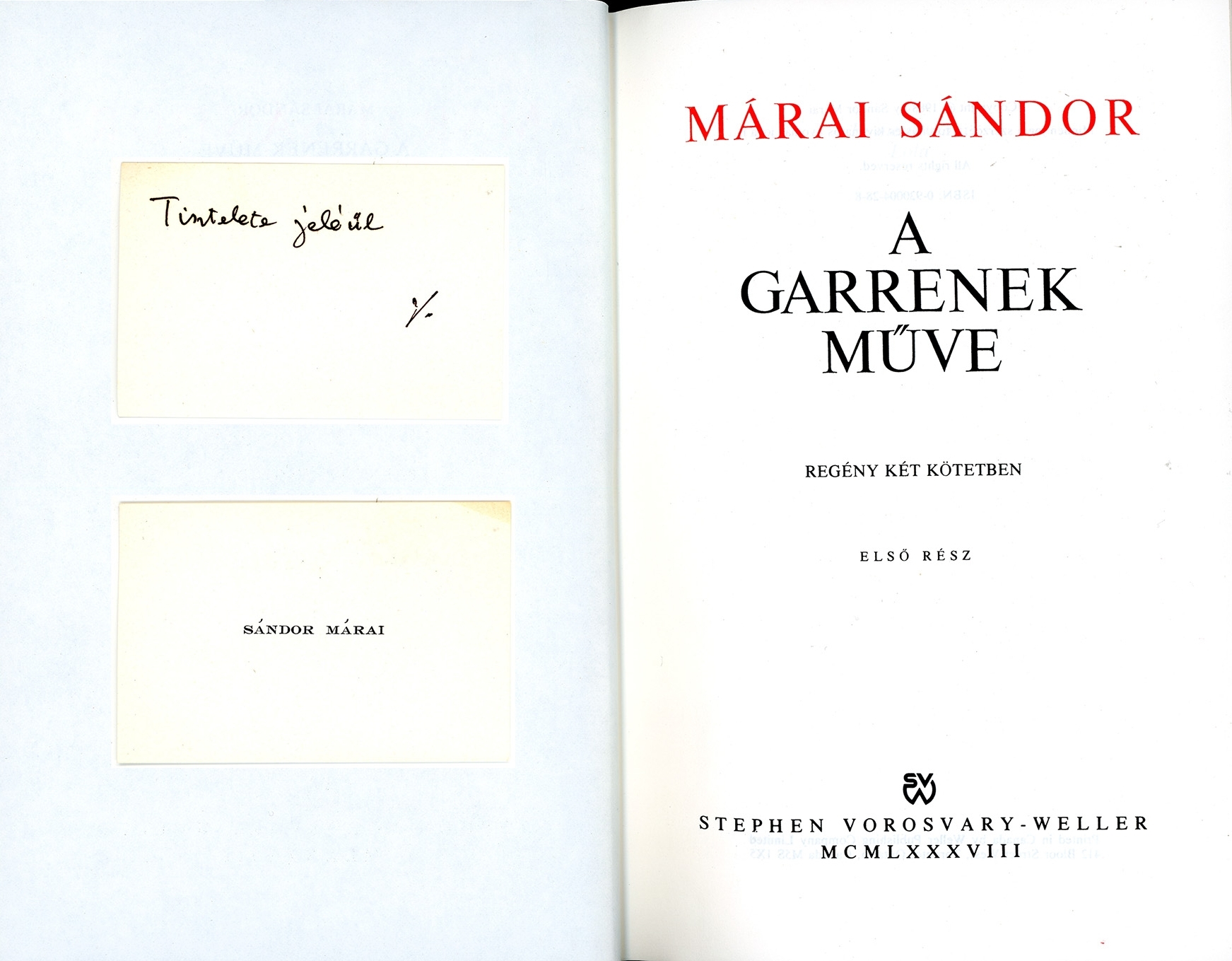

A Garrenek műve (The Work of the Garrens) from the library of Otto von Habsburg, with the name card of Márai enclosed

At 88, he lived to hold his magnum opus that came out of the press of István Vörösváry in Toronto. In the novel sequence, Márai evoked – and thus recreated – the atmosphere that emanated from the bourgeois world, which had irrevocably sunk with 1914, and which he experienced most strongly in Košice and Cluj-Napoca, and which he commemorated in several works, including Egy polgár vallomásai (Confessions of a Bourgeois), A gyertyák csonkig égnek (Embers, 2001), and perhaps most successfully in Szindbád hazamegy (Sindbad Goes Home). He sent a copy of the book to Otto von Habsburg as well. This greeting below from the former Crown Prince, who, in the decade since the Yalta Book became a leading European politician, is the last known piece of correspondence between the two.

|

On 22 October 1988. Esteemed, dear Márai! I gratefully thank you for having been kind enough to send me your wonderful new edition of your two-volume work “The Work of the Garrens”. I came to know about it through a newspaper article, and I am all the happier to have it in my possession. I hope to find some time to read it over the Christmas break – I know I will enjoy it immensely. With repeated thanks and lots of good wishes, Warmest regards, OTTO VON HABSBURG |

Four months after receiving the letter, the writer’s earthly existence came to an end on 21 February 1989.

Ferenc Vasbányai

[1] HOAL I-2-b-Márai Sándor. The Hungarian text is presented verbatim in the Hungarian version. I want to thank Tibor Mészáros and Csaba Komáromi of the Petőfi Literary Museum for their help in providing access to the Márai letters preserved by the institution.

[2] Márai inaccurately recalls the date of the coronation of Charles IV and Zita, which was held in Buda on 30 December 1916.

[3] As was his wont, he typed the letters, along with the envelope address, and only signed the letters by hand.

[4] A teljes napló, 1982–89 (The Complete Diary, 1982-89). Budapest, Helikon, 2018, 367.

[5] At Emil Csonka’s request, from 1964, he contributed to the Új Európa, a journal backed by Otto von Habsburg. On this issue, see Ferenc Bodri: Márai Sándor jelenléte a müncheni Új Európában. (Sándor Márai’s presence in the Munich New Europe.) Forrás, 1992, 7, 38-50.

[6] See: Jalta és ami utána következett. Válogatott cikkek, tanulmányok (Yalta and what followed. Selected articles and studies). München, Griff, 1979.

[7] A teljes napló, 1978–81 (The Complete Diary, 1978–81). Budapest, Helikon, 2017, 124.

[8] Ibid., 171.