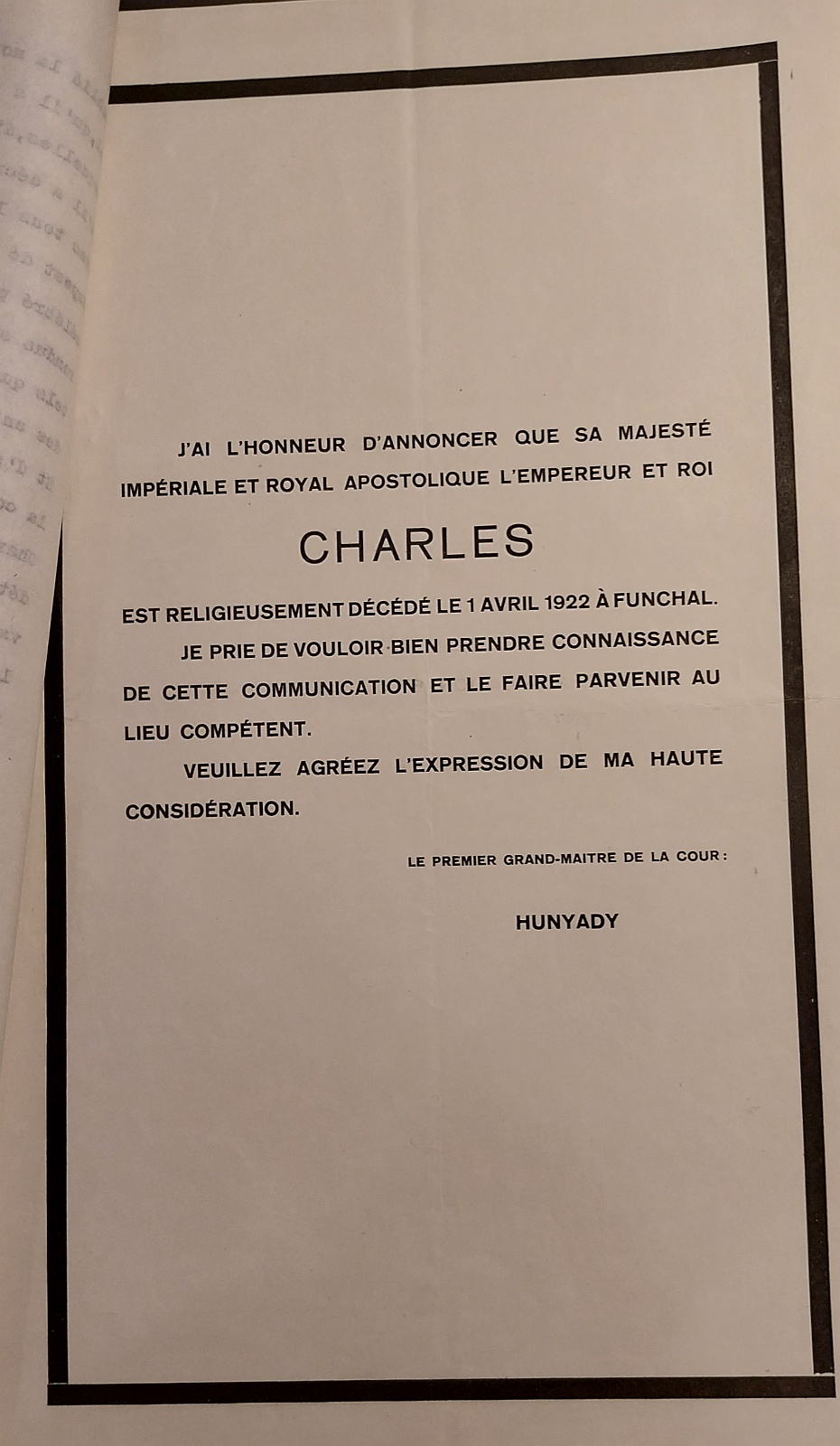

While researching archival sources, I came across thousands of pages on Otto von Habsburg and his family. The documents confirm that Belgian diplomacy anxiously followed King Charles IV’s months in Switzerland, his attempts to return to the Hungarian throne, as well as his exile in Madeira. Interestingly, it came to light that the Holy See had counted on the help of Belgium – from a member of the Council of Ambassadors – to help turn the fate of the Habsburg family in a positive direction; however, Brussels was careful to align itself with the French position on all the issues raised.

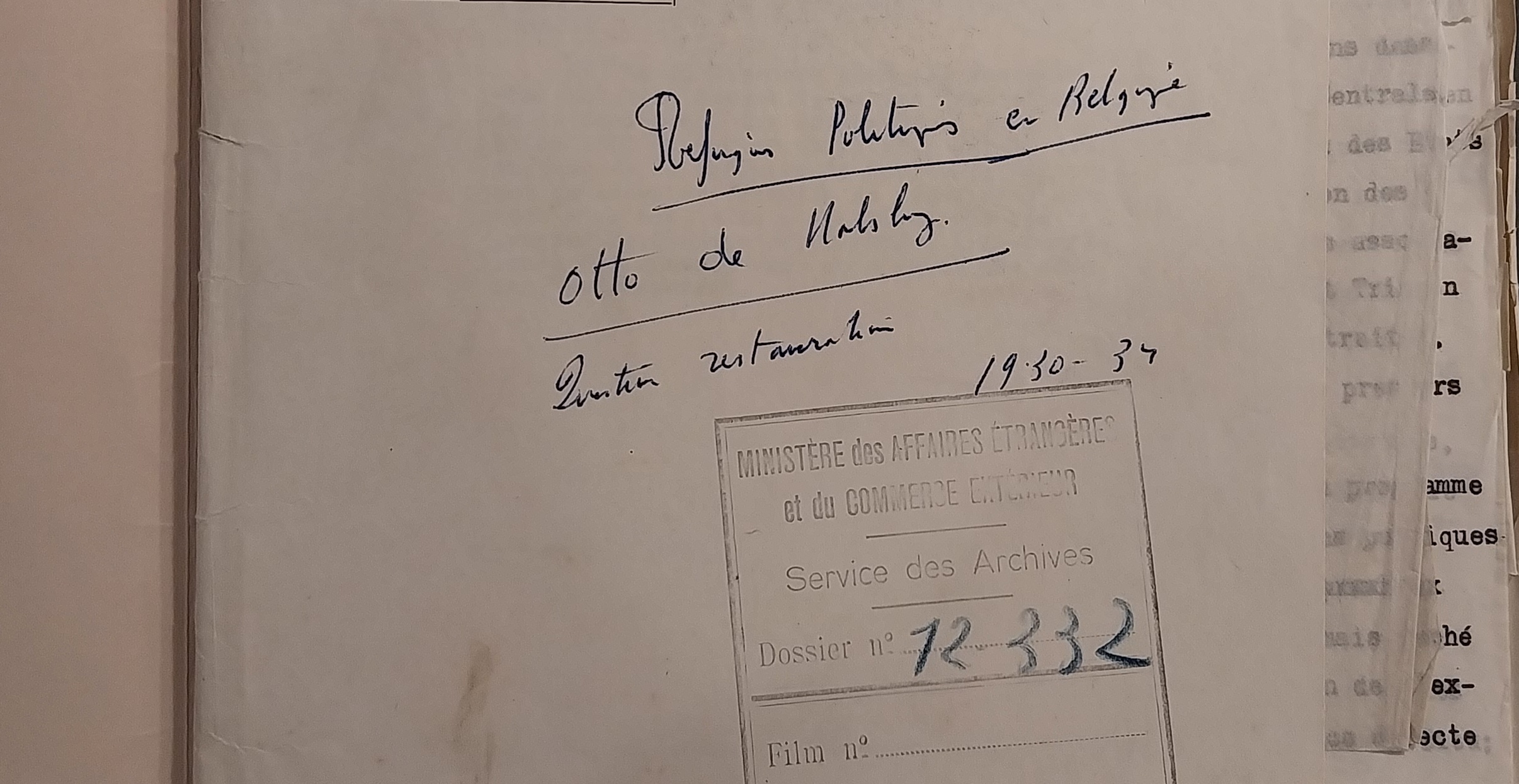

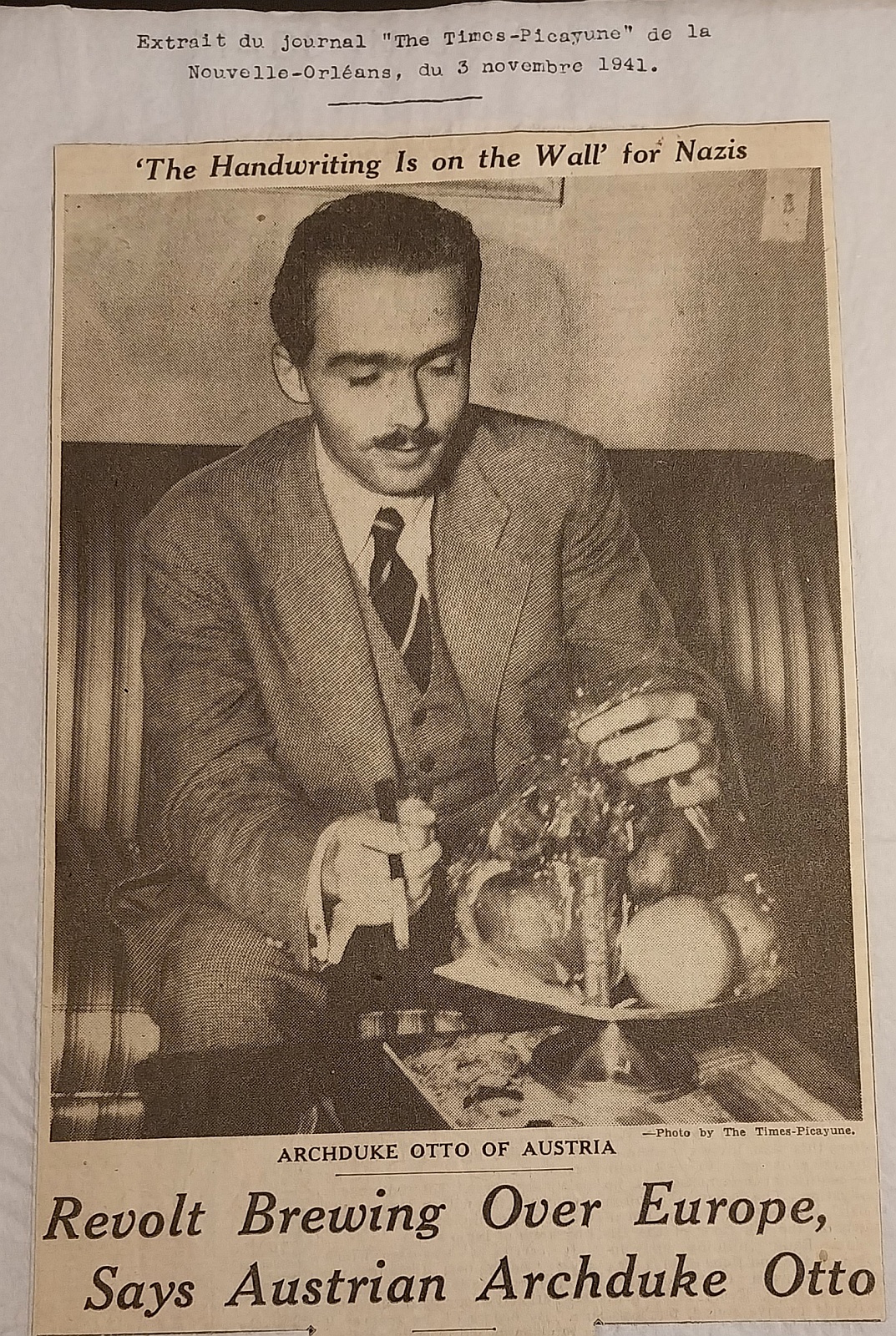

Specific files testify to the fact that during Otto von Habsburg’s stay in Belgium between the two wars, especially after he came of age, certain Belgian political circles were concerned about his international activities, especially his struggle against the Anschluss. It is known that Queen Zita and her children enjoyed the hospitality of the Kingdom of Belgium between 1929 and 1940, although the official authorities expected the family to renounce any public activity. This promise was often rather challenging for Otto von Habsburg to keep in the increasingly gloomy European context under the threat of Hitler. On several occasions, the Belgian aristocracy stepped in to cast a benign shadow over the former heir to the throne’s activities.

A fascinating dossier in the Belgian Archives of Foreign Affairs deals with the history of diplomatic passports granted to the former royal family. These documents, issued in Brussels, were more than once the target of Otto von Habsburg’s political enemies, for example, when the emigrant Czechoslovak government insisted on their withdrawal during the Second World War.

All in all, the findings of the research in the Belgian Archives of Foreign Affairs will significantly help the processing of the collection material held in the Otto von Habsburg Foundation. Furthermore, in some cases, they supplement our knowledge of the former heir to the throne’s oeuvre with new information.

In conclusion, in the 20th century, the German Lowlands, once under Habsburg rule, continued to maintain a special relationship with the last monarch of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his family, and the examined papers testify to this.

Gergely Fejérdy