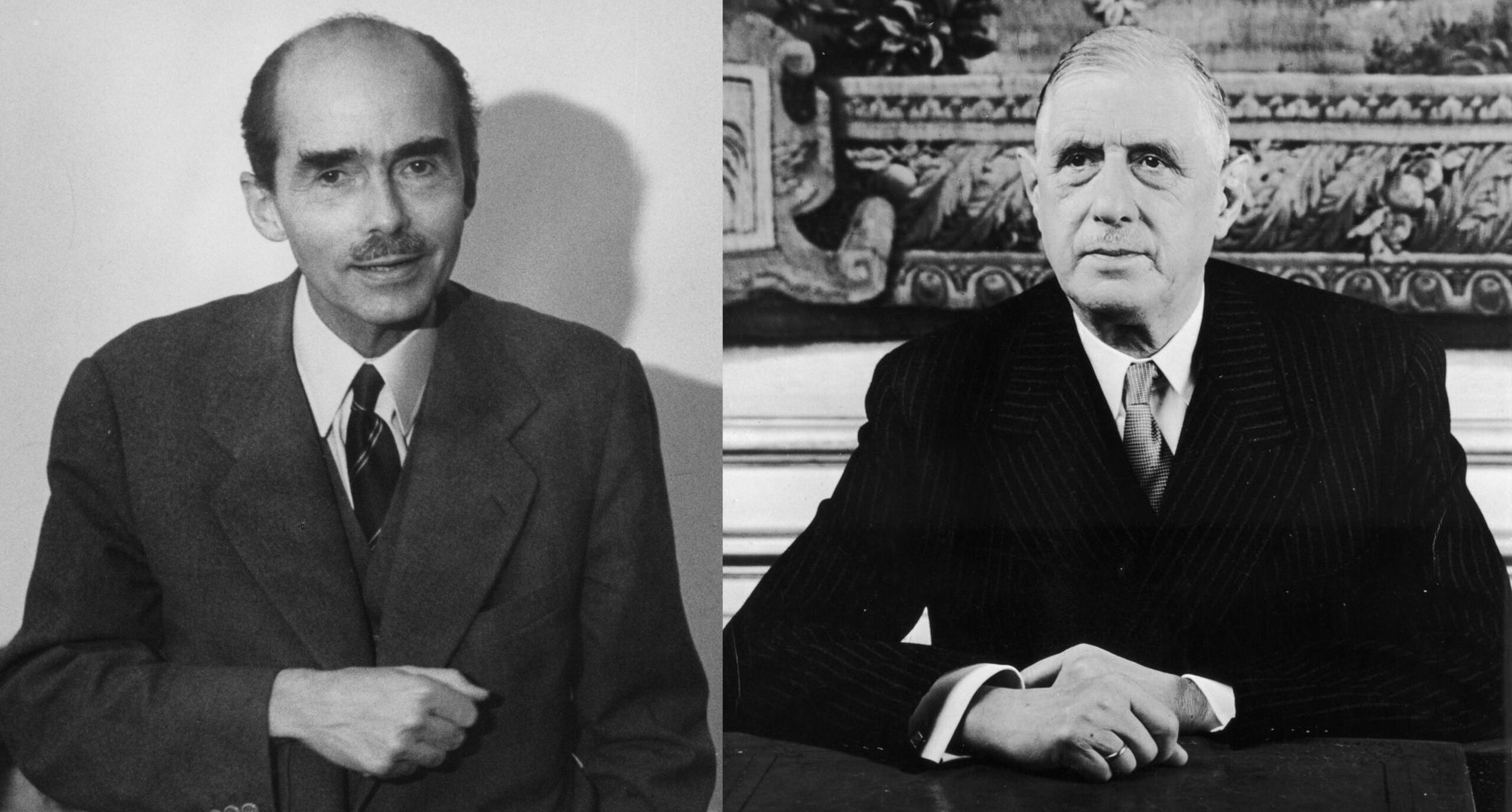

Few know, but the former Crown Prince and the French President had a friendly relationship. Otto von Habsburg first met Charles de Gaulle, Secretary of State for Military Affairs in the government led by Prime Minister Reynaud in the summer of 1940, eighty years ago. The former Crown Prince knew the Prime Minister well and the Minister of Interior, Georges Mandel was his friend. Owing to the latter had he access to the ministries and was able to help many refugees in those dramatic days. He also became acquainted with De Gaulle through his charitable work.

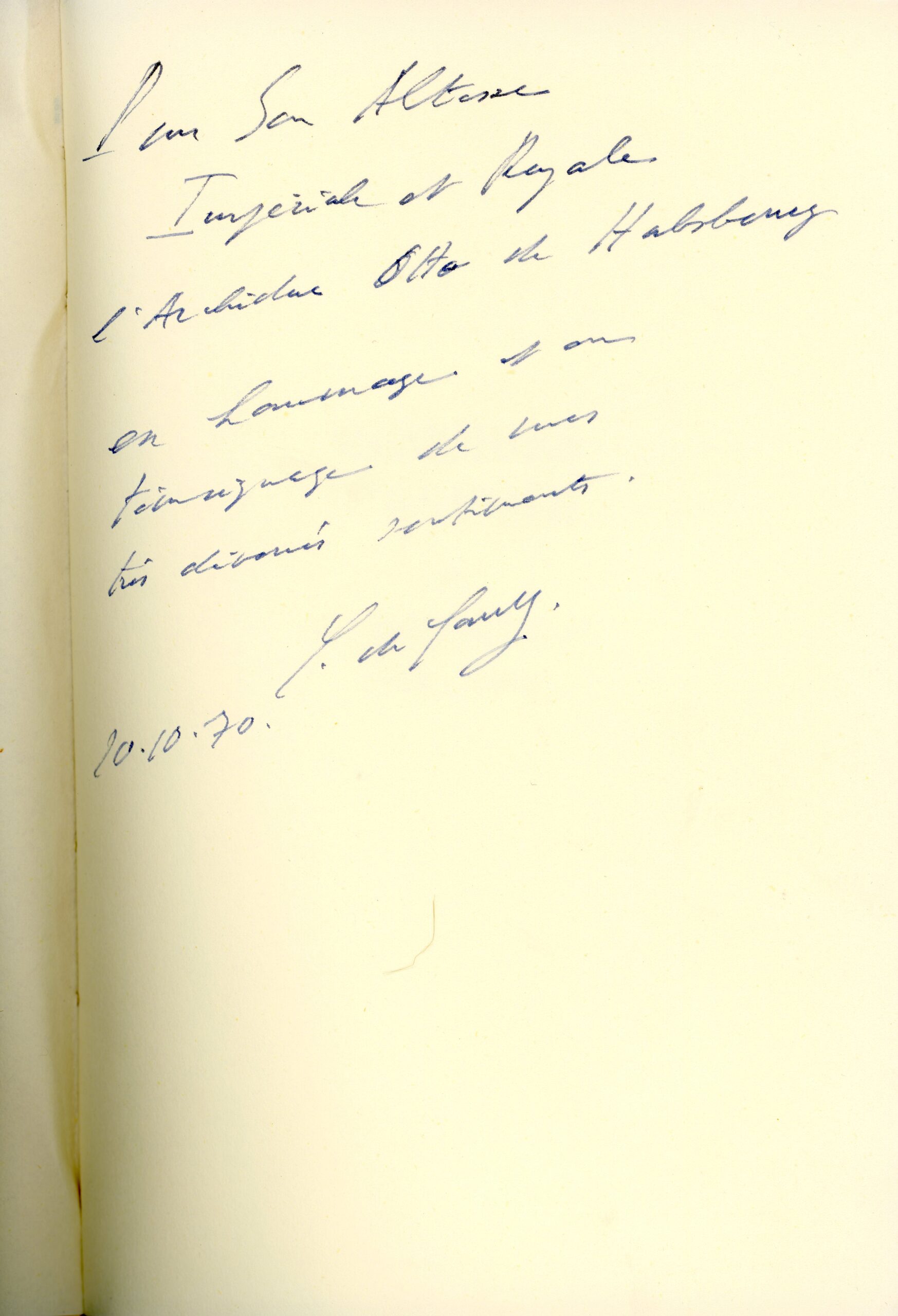

Otto von Habsburg and the French statesman met several times after the war, and from 1960 they began personal correspondence. The former Crown Prince let his works, published in French in the 1960s, to be delivered to the President of the Republic of France. The gesture was highly appreciated. In return, he sent Otto a dedicated first volume of his memoirs (Mémoires d’espoir). Otto von Habsburg considered De Gaulle an eminently wise, visionary, exemplary Christian European statesman. It is no coincidence that the news of his death had a profound effect on him. This is evident from a letter dated 12 November 1970 written for his friend Michel Debre, who was then Pompidou’s Defence Minister and a direct colleague of De Gaulle’s: “I would like to indicate in the lines below how much I felt with you and thought about you during these so painful hours. Knowing that you were one of the General’s most loyal associates, I can imagine what his unexpected passing means to you. But you can be sure that many Europeans also share this loss wholeheartedly. I am equally confident in your commitment to continue working together to bring to life on our Continent the ideas and thoughts represented with greatness and dignity in the life of the General. We must do so in order for his heritage to remain fully alive. You will always be able to count on your loyal friends in this task. Praying with you for the peace of mind of the departed great Christian, please, Your Excellency, receive my distinguished and friendly greetings.”

A volume dedicated to Charles de Gaulle in the collection of the Otto von Habsburg Foundation

“To the Imperial and Royal Highness, Archduke Otto von Habsburg, as a testimony for my respect and devotion. October 20, 1970. “

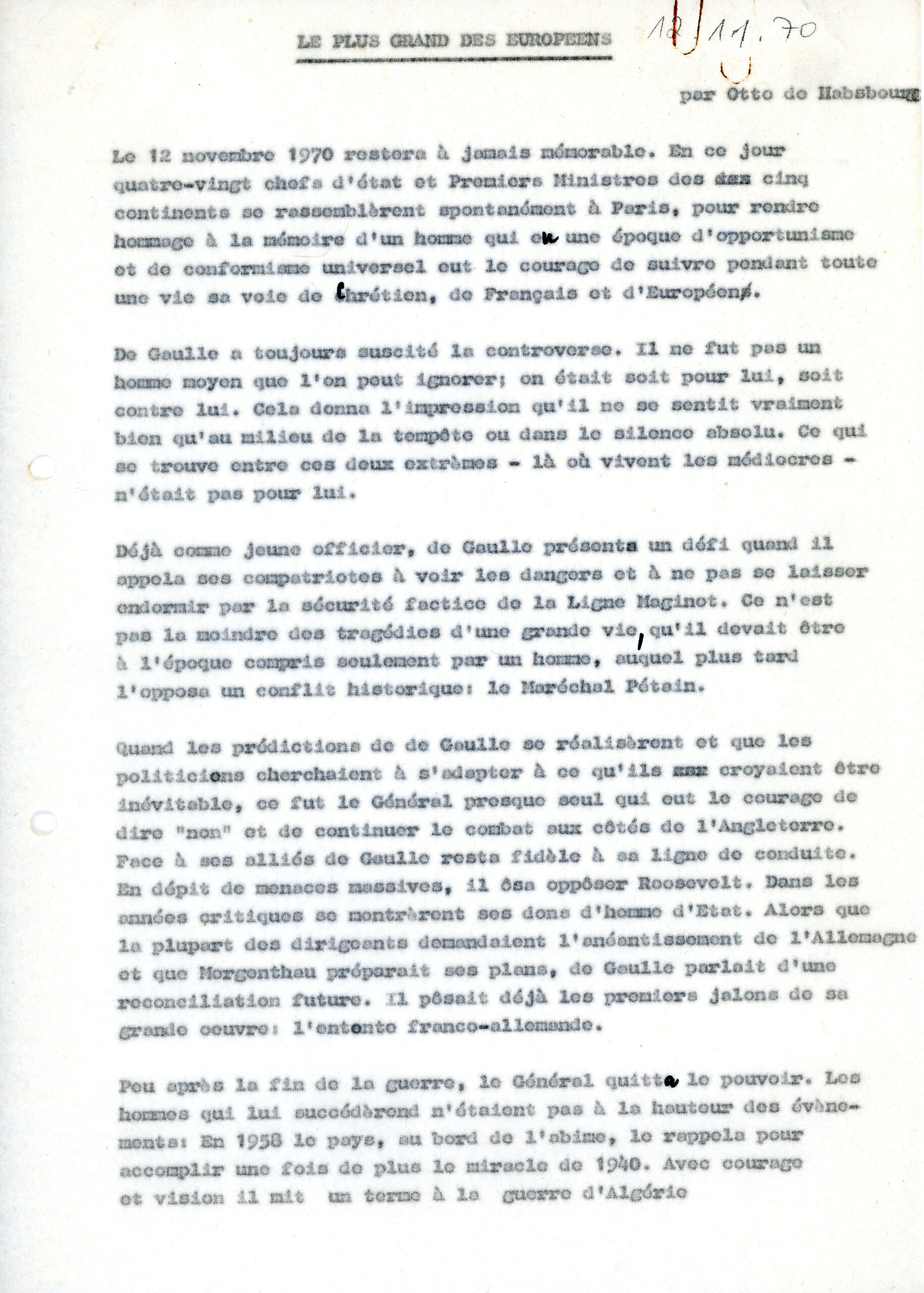

On the same day, the day of Charles de Gaulle’s funeral, Otto von Habsburg wrote an article.

The manuscript of the French text, which can also be considered a mourning speech, can be found in the Collection of the Otto von Habsburg Foundation. Its English translation can be read below:

“The greatest European

November 12, 1970 will remain memorable forever. On this day, eighty heads of state and prime ministers of five continents gathered voluntarily in Paris to pay tribute to someone who, in an era of opportunism and universalist conformism, was brave enough to follow his own Christian, French, and European path.

De Gaulle’s personality has always provoked controversy. He was not an average person to be ignored: one took a stand either for or against him. This gave the impression that he was just feeling well either only in a storm or only in perfect silence. Everything between these two extremes – where the average person lives – was not for him.

De Gaulle had already challenged his contemporaries as a young officer when he called their attention to the danger and did not allow them to be put to sleep by the fake safety of the Maginot Line. The great tragedy of his life was that he later came into historical conflict with Marshal Pétain – the only man who could have understood him.

When his prophecies became a reality and politicians tried to adapt to the situation, they thought evitable, he alone had the courage to say “no” and continue to fight alongside England. De Gaulle remained true to his line, even against his allies. Despite all the strong threats he had the courage to stand against Roosevelt. In the critical years, his talents as statesman became apparent. While most leaders demanded the destruction of Germany and the Morgenthau plan was completed, he spoke of future reconciliation. He had already laid the first milestones of his great work: the Franco-German Compromise.

Shortly after the war, the general resigned. Those who followed him were not capable of coping with the situation. The country on the brink of the abyss recalled on him in 1958 to once again perform the 1940 miracle. He ended the Algerian war with foresight and courage and gave the Fifth Republic a constitution that is still one of the most modern fundamental laws in Europe today. The success of his work is demonstrated by the fact that, since then, all parties, with the exception of the Communists, have seen themselves as custodians of the institutions they had criticized a few years earlier.

This orientation of public life coincided with economic plans. Force de frappe (nuclear deterrence) and modern scientific policy have stopped the brain drain. Today, France is one of the most developed countries in the world in many areas, thanks above all to this great man.

General De Gaulle was accused of being an enemy of European unity. This claim was born of malicious propaganda. Of course, he didn’t want an American-type Europe that some technocrats dreamed of. He wanted a European Europe that did not sacrifice spiritual values on the altar of false development. That is why De Gaulle did more for Europe than most of his contemporaries. Not only the Franco-German reconciliation, one of the most positive facts in recent decades, is an example to underline that, but also the road to political Europe opened up by the Fouchet plan. It was not De Gaulle who overturned this initiative. And the so-called inconveniences he caused to the Common Market did not hurt the Community.

Even his enemies had to admit that the greatness of the general became clear when he retired. His behaviour at that hour was reminiscent of the most beautiful hours in history, the last days of Charles V in Yuste. This silence is the ultimate proof of the spiritual strength of a man of exceptionally strong character, a man who has stood at the helm for a long time. The greatest wisdom is to recognize that the time has come.

Most of our contemporaries in the press will quickly be forgotten, but De Gaulle entered History as a soldier, politician, thinker, and writer — in short, as a statesman. His oeuvre is not only the property of the French nation, but also part of our European heritage.”

The manuscript of the writing in French in the collection of the Otto Habsburg Foundation

To the best of our knowledge, Otto von Habsburg’s article did not appear in this form. However, it faithfully reflects the views of the former Crown Prince, who said that the life and behaviour of the deceased “Christian, French and European” statesman is a kind of compass that can still be instructive in public life.

Gergely Fejérdy