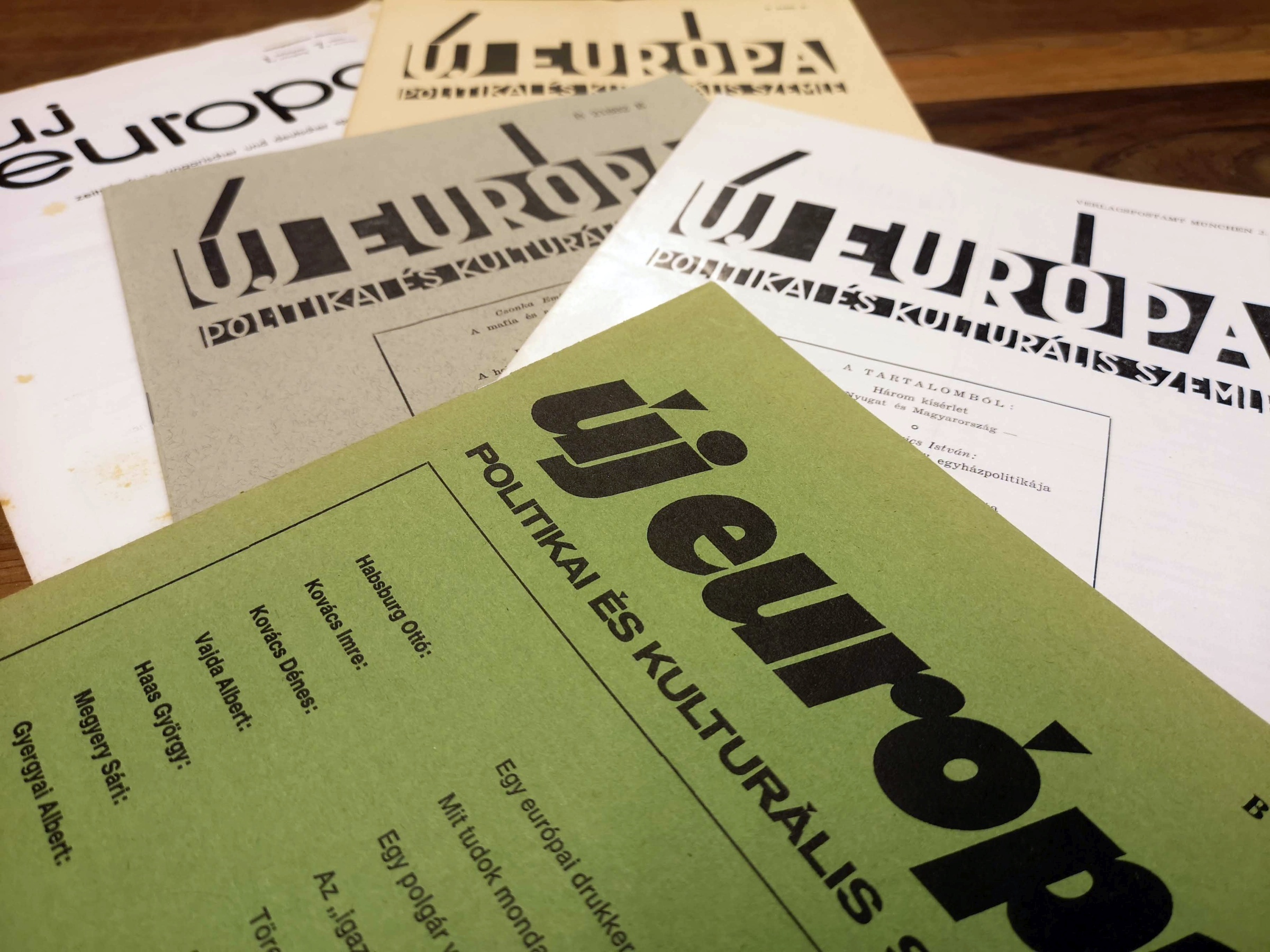

Új Európa [New Europe]

For nearly two decades, the papers’s image was shaped by the editorial work of Emil Csonka, who was in constant consultation with Otto von Habsburg, who determined the direction of the publication.[1] Csonka was born in Szombathely in 1923. He attended literature, history and sociology classes at Pázmány Péter Catholic University. In 1944, he held high positions in the youth organisation of the Arrow Cross Party and the propaganda secretariat of Szálasi—therefore, he fled to the West. From 1951, for three decades, he worked for Radio Free Europe.[2] He took over the editorial reins of the journal in November 1963, and from then on, his cooperation with Otto in maintaining the outlet and ensuring an adequate standard of publication proceeded smoothly. Due to the former Crown Prince’s network of connections, Új Európa soon became an instrumental forum for information on foreign policy in the emigration community.[3] Although the reputation of Csonka among Hungarians abroad was, to say the least, not unanimously positive,[4] Otto trusted him, appreciated his diligence and organisational skills, and did not object when his editor wrote a book about him in 1972, and a few years later about his mother as well.[5] He praised his former colleague upon his untimely death with the following words: “…We seldom find anyone who was such an ardent patriot as Emil Csonka, who expressed this nationalist spirit in such a wide range of literary and other activities.” [6]

Political journalism of Otto in the newspaper

The hallmark of Otto von Habsburg’s writings in Új Europa is to outline a broad-brush tableau and then approach the specific topic from an elevated perspective. His recurrent themes are the United States, the Soviet Union and East-Central Europe, China, the Far East, and European integration—although it is hardly an exaggeration to claim that the author delineates the contours of world politics in the background in nearly every instance. He returns in several articles to the politicians he considers prominent and to personalities he feels close to, such as Konrad Adenauer, Charles de Gaulle, Salvador de Madariaga, Richard Nixon, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, József Mindszenty, Leo Tindemans, Franz Josef Strauss and Sándor Márai. The essays range from one to four pages in length, with only a few occasional multi-part pieces—usually extracts from his forthcoming books. In honour of his 70th birthday, a compilation about him was published in the 6th issue of the 1982 edition. In the following, I wish to highlight a few of Otto von Habsburg’s thoughts to encourage further research. (For details of his publications and the contents of the thematic booklet, see below.)

Otto’s first article appeared in the year of the journal’s launch. In the October issue, he commemorated the Hungarian Revolution, cautioning that its lessons were relevant to the fate of the whole continent: “Above all, we must create unity in Europe within the free world itself. In the days of the War of Independence, the Hungarian people’s cries for help were directed to this Europe as well. They who stood in that lost position believed in the European ideal, while the West only talked but otherwise remained inactive. There can be no doubt nowadays that if a United Europe had become fact and reality in 1956, the course of events would have been radically different.” (highlighted from the original)[7] A decade and a half later, on the 20th anniversary of the Revolution, he addressed once again the responsibilities and duties of the whole of Europe, warning the prosperous democracies against the dangers of complacency and reminding them of their obligations to the oppressed nations of East-Central Europe: “Freedom will triumph if we, who enjoy its benefits, do not treat it as guaranteed, but act ceaselessly for the immortal ideals for which 20 years ago the Hungarian nation stood up for, and defied the armoured tanks of tyranny with their bare hands.” [8]

The Hungarian theme was constantly present in his writings: on the occasion of anniversaries and individuals, he regularly expressed his thoughts on the motherland, emigration, and the relations between the region and Europe within the field of the great powers. He sought encouragement in each event, to set an example for his readers. The fate of Mindszenty—through his personal involvement, the legitimist conviction of the Prince-Primate, and their meetings after the Archbishop’s departure to the West—provided a perfect example: “Mindszenty’s path is straight as an arrow, from start to finish. In the eight decades of his life, we find neither sly compromises nor ambiguous agreements with those in power. Naturally, this is not to the liking of the alleged diplomats, the schemers in office. They disguise their shortcomings as prudence, and the witness—the martyr, for whom faith is a sacrifice and not a sinecure—such a witness is an eternal reproach to the opportunists” [9]; he addressed the Cardinal’s supporters and critics.

The question of returning the Holy Crown home was doubtlessly the one that stirred the Hungarian community the most in the 1970s: the Carter administration’s gesture elicited a reaction from the Hungarian community worldwide. Otto von Habsburg was against the diplomatic action of the United States. Nevertheless, as so often in his life, he proved to be a gifted oracle: “Today, the dictatorship still rejoices with great triumph that it has achieved a tremendous foreign policy success, and it cannot be denied that the present American course has delivered this victory to the doorstep of this tyranny. However, just as the »Mindszenty affair« has taken on different dimensions from those intended by its directors, it cannot be ruled out that the Crown will also assert its independence, that it will surpass the diplomacy of the Soviet colonial empire on the Danube, and that the Holy Crown will enter into a strong and lasting alliance with the Hungarian people on Hungarian soil.” [10] In 1979, revisiting this subject, he assessed it as follows: “…what has been happening for a year, since the return of the Crown, is a kind of blessed complicity in the absence of free elections, a type of referendum against foreign occupation, against dictatorship, respectfully in favour of a multi-party system, parliamentary democracy, freedom of conscience and religion, freedom of association, freedom of the press and expression—in support of human rights. A referendum to restore normalcy to life along the Danube. A silent protest, a clear signal of a nation’s will to live. It is a referendum, as was the movement of the Hungarian emigrant community, when it focused and continues to focus the world’s attention on the cause of Hungarian independence through the Crown, tenaciously, consistently, and ceaselessly. The same resolve, purpose, and spirit at home and abroad—one nation in all parts! What the history of the last years of the Crown has taught us, and what this history testifies to, is nothing less than that there is Hungarian national unity, even in adversity. It is a reassuring phenomenon.” [11]

He repeatedly warned that the improvement of the financial living conditions of a society—as it happened in the West—cannot be an end in itself for human existence. Confronted with the increasing signs of crisis in the 1970s, he urged a return to the moral principles that had defined Europe’s identity from the outset and the imperative to rediscover them: “The cause of the decline of the »Old World« is not material. Western Europe is rich, being the second largest economic power in the world. Its human resources are not to be underestimated: two hundred and fifty million talented people, a population greater than that of either America or the Soviet Union. The decadence of Europe can be perceived on the planes of spirit, character and morality.” [12] The opportunity to participate actively in politics emerged when he was elected, from the top of the CSU list, a member of the European Parliament in 1979, which, for the first time in the history of integration, decided on the representation of member states by direct votes of citizens. As usual, he was looking forward to the challenge with high hopes and, in fact, saw in it the promise of fulfilling a dream: “Victory is not impossible. There is a way to secure a Christian future for Europe once again. Neither our faith nor our continent is destroyed. Our values will only perish if we give them up. Let us remember: Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing.[13] However, for those endeavouring to unite Europe, the time of idleness, of ‘dolce far niente’, is gone forever. Triumph and defeat are both in our hands. We are responsible for our actions towards God, the future generations of Europe, and European Christian civilisation.” [14]

One could quote at length from the writings of Otto von Habsburg. I hope that these few passages have sparked the reader’s interest. If so, one should be aware that within the public collections, only the National Széchényi Library holds the entire collection of the emigrant journal; some of its volumes are available in electronic form on the Arcanum Digital Library (for the period between 1966 and 1983) and on the website of Új Látóhatár [New Horizon] (for the issues of 1968-1970). On the latter site, an informative introduction by its editor, Pál Szeredi, places the press product on the intellectual and political map of the period.

In our Digital Archive, you can find all of Otto von Habsburg’s articles published in this journal by clicking here. We wish you a pleasant browse!

Ferenc Vasbányai

Otto von Habsburg’s writings in the Új Európa magazine (1962–1983)

1962

Európa nagyhatalmi szerepe. Dr. Habsburg Ottó előadása. [Europe’s role as a Great Power. Lecture by Dr. Otto von Habsburg.] 2., p. 5–8.

Quemoy: sziget az oroszlán torkában. [Quemoy(Kinmen): Island in the Lion’s Den.] 3., p. 5–6.

Az európai föderáció néhány kérdése. [A Few Questions on the European Federation.] 4., p. 5–6.

A magyar forradalom nem lezárt esemény. [The Hungarian Revolution is an Ongoing Affair.] 6., p. 5–7.

Hogyan tanultam magyarul. [How I Learned Hungarian.] 7., p. 5–6.

1963

De Gaulle, Kelet és Nyugat. Mit akar a francia államfő. [De Gaulle, East and West. What the French President Wants.] 1., p. 5–7.

Világpolitika mint feladat. [World Politics as a Mission.] 2/3., p. 5–6.

Néhány merész és új gondolat. [Some New and Bold Ideas.] 2/3., p. 6–8.

Korunk társadalmi problémái. [The Social Problems of Today] 7., p. 5–8.

Az ostromlott erőd. Vietnami útijegyzet. [The Besieged Fortress. Vietnam Travel Notes.] 9., p. 5–7.

A nagy kancellár műve. Konrad Adenauer. [The Work of the Great Chancellor. Konrad Adenauer.] 11., p. 5.

1964

Az atomkor új társadalma. [The New Society of the Nuclear Age.] 1., p. 5–7.

A medve és a sárkány. A szovjet-kínai ellentét történelmi gyökerei. [The Bear and the Dragon. The Historical Roots of the Soviet-Chinese Controversy.] 2., p. 5–7.

Oroszország dilemmája. Moszkva két tűz között. [Russia’s Dilemma. Moscow Caught Between Two Fires.] 3., p. 5–7.

Materialista ellenérvek. Az abortusz-kérdés. [Materialistic Counter-arguments. The Abortion Debate.] 7/8., p. 5–6.

Eseményekben gazdag ősz. [An Eventful Autumn.] 12., p. 5–6.

1965

Európai kiegyezés? De Gaulle és Kelet-Európa. [European Reconciliation? De Gaulle and Eastern Europe.] 3., p. 5–7.

Az igazi béke alapja. Bécs, Jalta és Európa. [The Foundation of True Peace. Vienna, Yalta and Europe.] 7/8., p. 5–6.

Az új ismeretek és a vallás. [New Perspectives and the Church.] 9., p. 5–6.

1966

Ázsiai jegyzetek. [Asian Notes.] 1., p. 5–6.

Egy nagyszerű liberális. Salvador de Madariaga. [The Excellent Liberal. Salvador de Madariaga] 7/8., p. 11.

Japán dilemma. [Japan’s Dilemma.] 9., p. 5.

1967

Változások a világban. [Changes in the World.] 3., p. 7–10.

Európa a Szovjetunió és Amerika között. Az európai egyesülés problémái. [Europe Between the Soviet Union and the United States. Problems of the European Integration.] 5., p. 7–10.

Az egész Európa. [The Entireity of Europe.] 11., p. 4.

1968

Reakciós elméletek alkonya. Modern szociálpolitika. [The Decay of Reactionary Theories. Modern Social Policy.] 5., p. 7–10.

Európa szociálpolitikai feladatai. Reakciós elméletek alkonya II. [The Social-Political Tasks of Europe. The Decay of Reactionary Theories II.] 6., p. 7–10.

Történelmi összefüggések. Budapest 1956 és Prága 1968. [Historical Contexts. Budapest 1956 and Prague 1968.] 10., p. 5–6.

1969

Mi várja Nixont? Külpolitikai körkép. [What is Nixon Facing? Foreign Policy Panorama.] 1., p. 7–11.

Mit várunk Nixontól. [Waiting for Nixon.] 3., p. 5–6.

Döntés Európáról. [Decision on Europe] 5., p. 7–9.

A tábornok távozása. De Gaulle lemondásának okairól. [About the Reasons Behind the Generals’ Resignation.] 6., p. 7–8.

1970

Ázsiai benyomások. [The Soviet-Chinese Conflict and Asia After Vietnam.] 2., p. 7–10.

Vita és felelősség. [The Crisis of the Church?] 4., p. 11.

A világhatalmak ereje és gyengesége. [The Strength and the Weakness of the World Powers.] 7., p. 7–10.

Elhallgatott tények. Jalta: ami előtte történt és ami utána következett. [Remembering Yalta. What Happened Before and What Came After.] 12., p. 7–10.

1971

Sztalin két történelmi tévedése. [The Two Historical Errors of Stalin.] 1., p. 7–11. (continuation of the Remembering Yalta article)

Peking és Közép-Kelet-Európa. Világpolitikai körkép. [The World Political Pole of China.] 6/7., p. 7–9.

1972

A helyszínen és előítélet nélkül. Afrika helyzete és problémái. [The Blacks and the Whites of Africa.] 1., p. 7–9.

A pekingi út. [The Beijing Way.] 2., p. 5. ( just a couple of lines)

Peking után, Moszkva előtt. [After Peking — Before Moscow.] 5., p. 7–9.

Európa – összefogás vagy összeomlás. [Fifty Years “Paneuropa”.] 8/9., p. 7–8.

Enyhülési eufória. [Nixon and Brezhnev.] 10., p. 5–6.

Mindszenty Bécsben. [Cardinal Mindszenty in Vienna.] 11., p. 7.

Nixon új megbízatása. [Nixon’s Victory.] 12., p. 7–8.

1973

A „kapitalista” Európa. [The “Capitalist” Europe.] 2., p. 5–6.

Kína és Európa közeledése. [China and Europe.] 3., p. 7–9.

1973[sic!] március 11. [The European Significance of the French Elections.] 4., p. 5–6.

Még egy szó Vietnámról. [South Viet Nam’s Perspectives.] 5., p. 5–6.

Addio Africa? [Addio Africa?] 6/7., p. 5–6.

A Nixon-Brezsnyev találkozó és Európa. [After Brezhnev’s Visit.] 8/9., p. 5–6.

A papírtigris ereje. [The Actual and Assumed Strength of the Soviet Union.] 10., p. 7–9.

Németország aláaknázása. [The Undermining of the Federal Republic.] 11/12., p. 5–6.

1974

A puszta tények. [Has the policy of detente brought any changes?] 1., p. 5–6.

Mindszenty neve örök. Az ember, aki mer nemet mondani. [Cardinal Mindszenty. The man who dares to say no.] 2., p. 7–8.

Európa Dünkirchene? [The Dunkirk of Europe?] 3., p. 7–9.

Európa egyik rákfenéje. [Democracy of Favors in Europe.] 4., p. 5–6.

Az európai biztonsági konferencia. [The European Security Conference.] 5., p. 7–8.

A tábornok unokája. [The general’s grandchild.] 6., p. 5–6.

1975

A Szovjetunió szerencséje. [The Luck of the Soviet Union.] 1., p. 7–10.

A hóhér kötele. [Soviet Armament.] 2., p. 5–6.

Ha Brezsnyev távozik. [When There Will No Longer Be a Brezhnev.] 3., p. 5.

A jövő győztese. [Cardinal Mindszenty’s Future.] 4., p. 5.

Leírjuk-e Amerikát? [Should We Write America Off?] 4., p. 7–9.

A szappanbuborék. [The Soap Bubble of Helsinki.] 5., p. 5–6.

Új világháború Ázsiában? [A New World War in Asia?] 5., p. 7–9.

Két oszlop Ázsiában. [Two Pillars in Asia: Japan and Taiwan.] 6., p. 7–9.

1976

Európában mozdul valami. [Tindemans’ Europe.] 1., p. 7–8.

Moszkva földközi-tengeri politikája. [Moscow and the Mediterranean Sea.] 2., p. 5–6.

Békétlen béke. [Why Is There No Peace?] 3., p. 7–8.

Pax Americana, ahogy én látom. [Pax Americana—In What Way?] 4., p. 5–7.

A magyar ötvenhat és a mi felelősségünk. Gondolatok a forradalom 20. évfordulóján. [1956 in Hungary and Our Responsibilities. Reflections on the 20th Anniversary of the Revolution.] 6., p. 7–10.

1977

Moszkva és Marokkó. [Moscow and Morocco.] 1., p. 5–6.

A spanyol fejlődés [The Evolution in Spain.]. 2., p. 5–6.

Cárok és marxisták. [Tzars and Marxists.] 3., p. 5–6.

Gondolatok az európesszimizmusról. [About Europessimism.] 4., p. 7–10.

Francia földcsuszamlás? [Internal Affairs in France.] 5., p. 5–6.

A 21. évforduló. [The 21st Anniversary of Hungary’s 1956 Revolution.] 6., p. 5–6.

1978

Mi és a kínaiak. [China and the West.] 1., p. 5.

A Szent Korona és a magyar nép. [The Holy Crown of St. Stephen and the Hungarian People.] 2., p. 7–14.

Emberi jogok és emberarcú szocializmus? [Human Rights and Socialism with a Human Face?] 4., p. 5–6.

„Mint Bercsényi és Türr István…” [Why I Became a German Citizen.] 5., p. 4.

Milyen Európát akarunk? [What Kind of Europe Do We Wish for?] 6., p. 7–8.

1979

A kínai kártya. [The Chinese Card.] 1., p. 7–8.

Még egyszer a Szent Korona: a második népszavazás. [The Holy Crown and the Hungarian Society of Today.] 2., p. 7–13.

Európa az Uraltól az Atlanti-óceánig? [Europe, From the Ural to the Atlantic?] 3., p. 7–8.

Új arcok, új jelenségek. [Three Portraits: Carstens, Khomeini, Muzoreva.] 4., p. 7–8.

Legfőbb feladatom az Európa-parlamentben. [My Main Task in the European Parliament.] 5., p. 7–9.

Franz Josef Strauss és a kancellárság. [Franz Josef Strauss and Chancellorship.] 6., p. 7–8.

1980

Négy szempont a világpolitikához. [Four Points of View, In Regard to International Politics.] 1., p. 7–11.

Egy európai drukker. A 80 éves Márai. [The 80-year-old Hungarian novelist Sándor Márai.] 2., p. 5–6.

A hatodik hadoszlop. [The Sixth Column.] 3., p. 5–6.

Európa veszélyes viselkedése. [Europe and America.] 4., p. 5–6.

Jó és megbízható partner. Ronald Reagan. [Ronald Reagan, Anderson and Carter.] 5., p. 5–6.

A totalitárius kihívás. [The Totalitarian Challenge.] 6., p. 7–12.

1981

Veszély északon. [Scandinavia and the Soviet Union.] 1., p. 5–6.

Egy európai drukker. A 80 éves Márai. [The 80-year-old Hungarian novelist Sándor Márai.] 2., p. 5–6. (reprint of the article published in 1980)

A terrorizmus és a Szovjetunió. [Terrorism and the Soviet Union.] 3., p. 5–6.

A Kreml ellentámadása. [Europe, America and the Kremlin.] 4., p. 5–6.

Tanúságtétel Európa mellett. A forradalom 25. évfordulója. [The Sense of the Hungarian Revolution 25 Years Ago.] 5., p. 5–6.

Szadat után. [After Sadat.] 6., p. 5–6.

1982

Fecsegés a kilépésről. [The Future of the European Community.] 1., p. 5–6.

Németország és Franciaország. [Germany and France.] 2., p. 5–6.

Az orosz dömping. [The Soviet “Dumping”.] 3., p. 5–6.

Illúziók felszámolása. [Making a Clean Sweep of Illusions.] 4., p. 5–6.

A leszerelési tárgyalások. [Questions of International Politics.] 5., p. 5–6.

1983

Az emigráns magyar. [The Hungarian emigrant.] 1., p. 3–4. (about Emil Csonka)

Writings in the 1982/6 issue of Új Európa devoted to Otto von Habsburg

Emil Csonka: Habsburg Ottó hét évtizede. 1982. november 20.: Habsburg Ottó 70 éves. [Seven decades of Otto von Habsburg. 20 November 1982.] p. 5–6.

Béla Varga: Tisztelet Habsburg Ottónak. [Homage to Otto von Habsburg.] p. 7–12.

József Mindszenty: A magyarság szolgálatában. [In Service to the Hungarian Nation.] p. 12.

Egon Jávor: A bencések tanítványa. [A Student of the Benedictines.] p. 13–14.

Leo Tindemans: Meggyőződéses, bátor ember. [A Man of Conviction and Courage.] p. 15.

Pierre Pflimlin: Született politikai tehetség. [A Natural Political Talent.] p. 15.

Habsburg Regina a magyar dohányvidéken. [Regina von Habsburg at the Hungarian Tobacco Belt.] p. 16.

Dávid Angyal: „Szorgalmasan jegyezgetett”. Ottó királyfiról. [“He was diligently taking notes”. About Crown Prince Otto.] p. 17–18.

Pál Auer: „Kitűnő ítélőképesség, elsőrangú tájékozottság”. A férfi Habsburg Ottóról. [“Excellent discernment, great knowledge”. On Otto von Habsburg, the Man.] p. 18–19.

Albert Vajda: Találkoztam a történelemmel. [I Encountered History Itself.] p. 20.

Szigorúan bizalmas: Habsburg Ottó persona grata. Magyar követi jelentések Ottóról, 1936-1939. [Strictly confidential: Otto von Habsburg persona grata. Reports of the Hungarian envoys on Otto, 1936-1939. .] p. 21–26.

Ferenc Móra: Szegény kis népcsászár! Móra Ferenc a kis Habsburg Ottóról. [Poor little People’s Emperor! Ferenc Móra on Young Otto von Habsburg.] p. 27.

[1] Their correspondence, which comprises about 700 documents and is awaiting processing in the Manuscript Collection of the Petőfi Literary Museum, was reviewed by Miklós Veres (Új Európa – Emil Csonka and Otto von Habsburg’s relationship. In: Habsburg Ottó és a rendszerváltozások. Ed. Ferenc Vasbányai. Budapest, Otto von Habsburg Foundation, 2021, 72-83.)

[2] “…Emil Csonka was among the most prolific colleagues; he worked with ease and speed, which was considered a major advantage in radio work…” as his former colleague noted. Gyula Borbándi: Magyarok az Angol Kertben. A Szabad Európa Rádió története. Budapest, Európa, 1996, 425.

[3] Gyula Borbándi: A magyar emigráció életrajza 1945–1985. Bern, Európai Protestáns Magyar Szabadegyetem, 1985, 292.

[4] István Deák: Maratoni életem. Emlékirat. Pécs, Kronosz, 2023, 248–249.

[5] Habsburg Ottó. Egy különös sors története. Munich, Új Európa, 1972. And Zita története. Az utolsó magyar királyné. Munich, Új Európa, 1975.

[6] Az emigráns magyar. Új Európa, 1983, 1, 3. [The Hungarian emigrant]

[7] A magyar forradalom nem lezárt esemény. Új Európa, 1962, 6, 6. [The Hungarian Revolution is an Ongoing Affair]

[8] A magyar ötvenhat és a mi felelősségünk. Új Európa, 1976, 6, 10. [1956 in Hungary and Our Responsibilities]

[9] Mindszenty neve örök. Az ember, aki mer nemet mondani. Új Európa, 1974, 2, 7. [Cardinal Mindszenty’s Name is Eternal. The man who dares to say no]

[10] A Szent Korona és a magyar nép. Új Európa, 1978, 2, 14. [The Holy Crown of St. Stephen and the Hungarian People]

[11] Még egyszer a Szent Korona: a második népszavazás. Új Európa, 1979, 2, 13. [The Holy Crown and the Hungarian Society of Today]

[12] Mindszenty neve örök. Az ember, aki mer nemet mondani. Új Európa, 1974, 2, 7.

[13] Otto quotes John Stuart Mill. The sentence is often wrongly attributed to Edmund Burke.

[14] Milyen Európát akarunk? Új Európa, 1978, 6, 8. [What Kind of Europe Do We Wish For?]