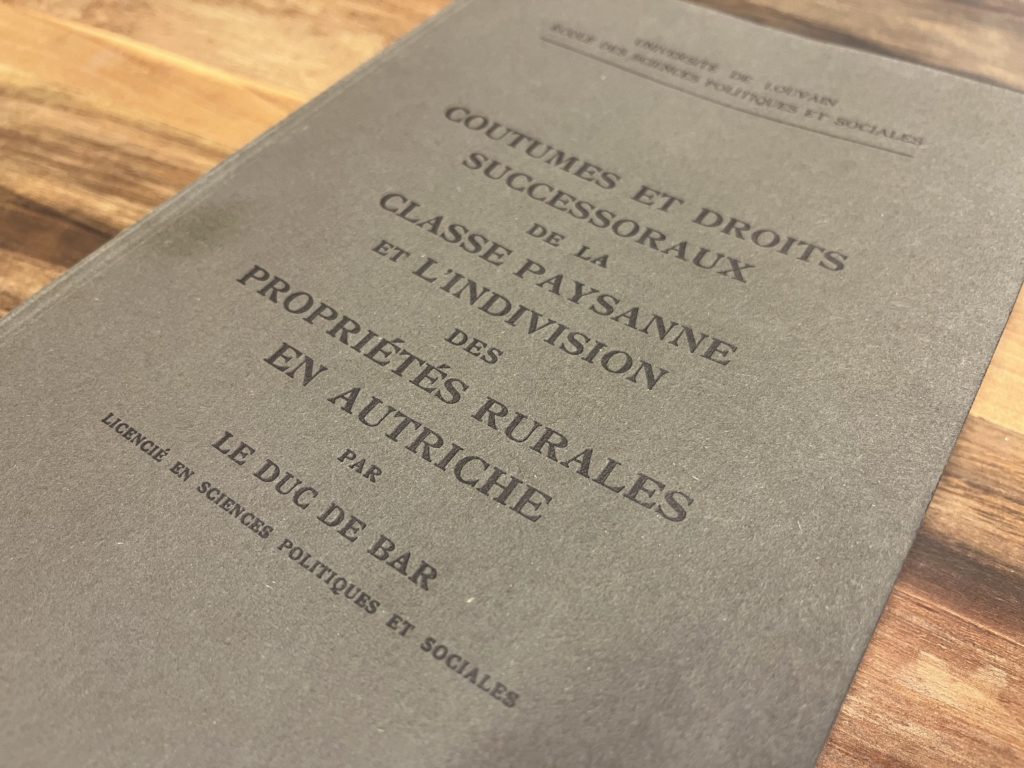

The former heir to the throne, who lived in Belgium with his family between 1929 and 1940, was a student of the 600-year-old Catholic University of Leuven. He graduated from the university’s renowned law faculty, where he had studied political science and social sciences, and wrote his doctoral thesis entitled Coutumes et droits successoraux de la classe paysanne et l’indivision des propriétés rurales en Autriche (Customs and Inheritance Rights of the Peasant Class and the Undivided Ownership of Rural Properties in Austria). He defended his dissertation ninety years ago, on 27 June 1935. Both the thesis and its defence were in French. The event took place in the ceremonial hall of the Catholic University of Leuven, commonly referred to as the Lakenhal. The building, located at 22 Naamsestraat, was constructed in 1317 for the city’s cloth weavers’ guild but has been used by the university since the 15th century.

A large committee attended the doctoral defence; according to contemporary press reports, 12 faculty members were present.[1] The meeting was chaired by Léon H. Dupriez (1901–1986), dean and professor of economics, who had earned his doctoral degree five years earlier. Dupriez was also briefly employed by the National Bank of Belgium, but worked continuously as a lecturer at the University of Leuven between 1930 and 1972. His career was characterised by a search for practical solutions and the more effective use of statistical data, as opposed to abstract economics. His methods influenced Otto von Habsburg’s thesis. Dupriez was close to Paul van Zeeland (1893–1973), the Catholic lawyer and politician who was Prime Minister of Belgium at the time, with whom Otto von Habsburg also maintained good relations.

At the thesis defence, both of Otto’s doctoral advisors were in attendance alongside the dean. From Belgium, Flemish politician Frans L. Brusselmans (1893–1967) arrived, a professor of law and member of the Catholic Party and the Belgian Economic Association, along with Max Sering (1857–1939), the era’s most renowned German agricultural economist. The latter expert, who taught at the University of Berlin, followed Otto von Habsburg’s progress for many years and even invited him to Germany to assist in assembling the source material for his dissertation. Viscount Charles Terlinden (1876–1972), a professor of history at the University of Leuven and a doctor of law, politics, and social sciences, as well as a close friend of the Habsburg family, also attended the occasion. Through both of his spouses – his first wife died young – Terlinden was a member of the Belgian political elite, while also participating in numerous public movements, primarily linked to the Catholic Church. His commitment to European unity and his strongly anti-Bolshevik views exerted a profound impact on Otto von Habsburg, who requested him to proofread his dissertation. In the published version of his thesis, he expressly thanked Viscount Terlinden for his help, and in 1954, Otto von Habsburg knighted him of the Order of the Golden Fleece in gratitude for his services to the family.

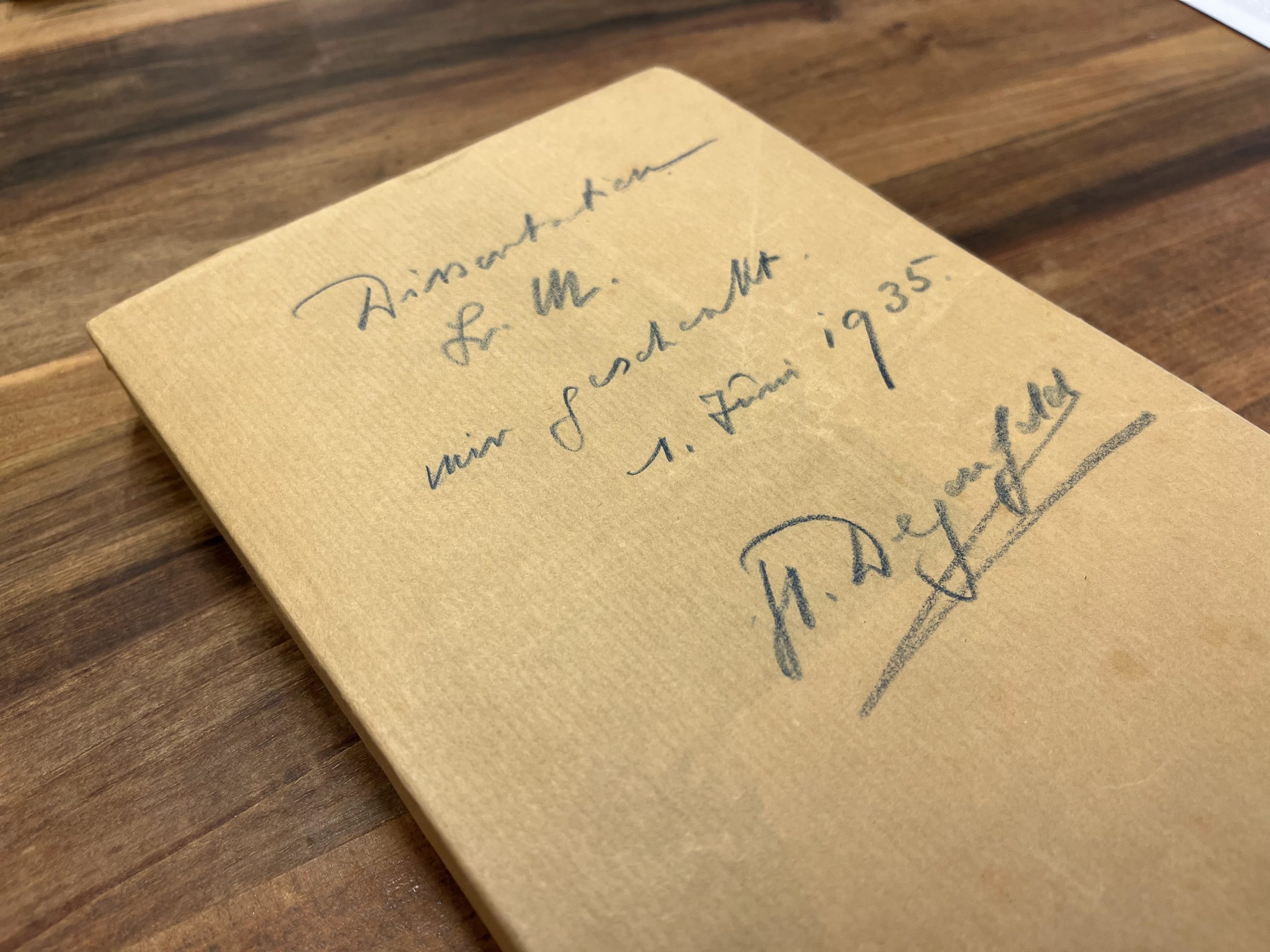

The audience included the entire family of the former Crown Prince: his mother, Empress Zita, and Otto’s seven siblings. The doctoral defence was closely followed by his eldest sister, Archduchess Adelheid, who defended her dissertation at the same faculty three years later. Several other relatives were also present, including Princess Isabelle of Bourbon-Parma and Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma. From Austria came Baron Hans Karl von Zeßner-Spitzenberg (1885–1938), a member of parliament, economist and professor at the University of Vienna, who three years later fell victim to National Socialist terror. They were joined in Leuven by Prince Erwein Lobkowicz (1887–1965) and the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne’s tutor, Count Heinrich von Degenfeld (1890–1978). Representing Hungary were Count János Zichy (1868–1944), former Minister of Education, who compiled Otto von Habsburg’s Hungarian curriculum and chaired his school-leaving examination committee; Count József Cziráky (1883–1960), a legitimist politician, imperial and royal chamberlain who was responsible for managing the remaining Hungarian assets of the Habsburg family, and Count Géza Pálffy, a landowner (1900–1952), a leading member of the Hungarian legitimist political faction, and Miklós Griger, abbot and parish priest (1880–1938), who was also a royalist and served as a member of the National Assembly for several terms during the period. Among Otto von Habsburg’s Benedictine teachers of Pannonhalma, Fathers Jácint Weber (1876–1939) and Jákó Blazovich (1886–1952) had come to listen to their former student’s doctoral defence.

Bishop Paulin Ladeuze, rector of the University of Leuven, welcomed those gathered in the university’s ceremonial hall. He warmly greeted the candidate’s mother, Empress Zita.[2] He recalled the centuries-old historical ties between Belgium (formerly part of the Low Countries) and the House of Habsburg, as well as the visit to the campus in 1617 by Isabella of Spain, daughter of Philip II, and her husband, Archduke Albert. The two illustrious guests were once received in the very hall where Otto von Habsburg had defended his doctoral thesis.

After the opening remarks, the dissertation evaluators presented their assessments, and Professor Dupriez summarised the review of the 358-page work. Otto von Habsburg responded to the comments in a coherent presentation lasting an hour and a half, recapitulating the most significant conclusions of his research. He argued the fundamental national interest in ensuring that medium-sized peasant estates remain undivided in the hands of a single family, claiming that supporting this is also beneficial to the state, as otherwise smallholders would become impoverished and ‘proletarianised’, which could lead to serious social consequences. The committee accepted the answers of the former heir to the throne.

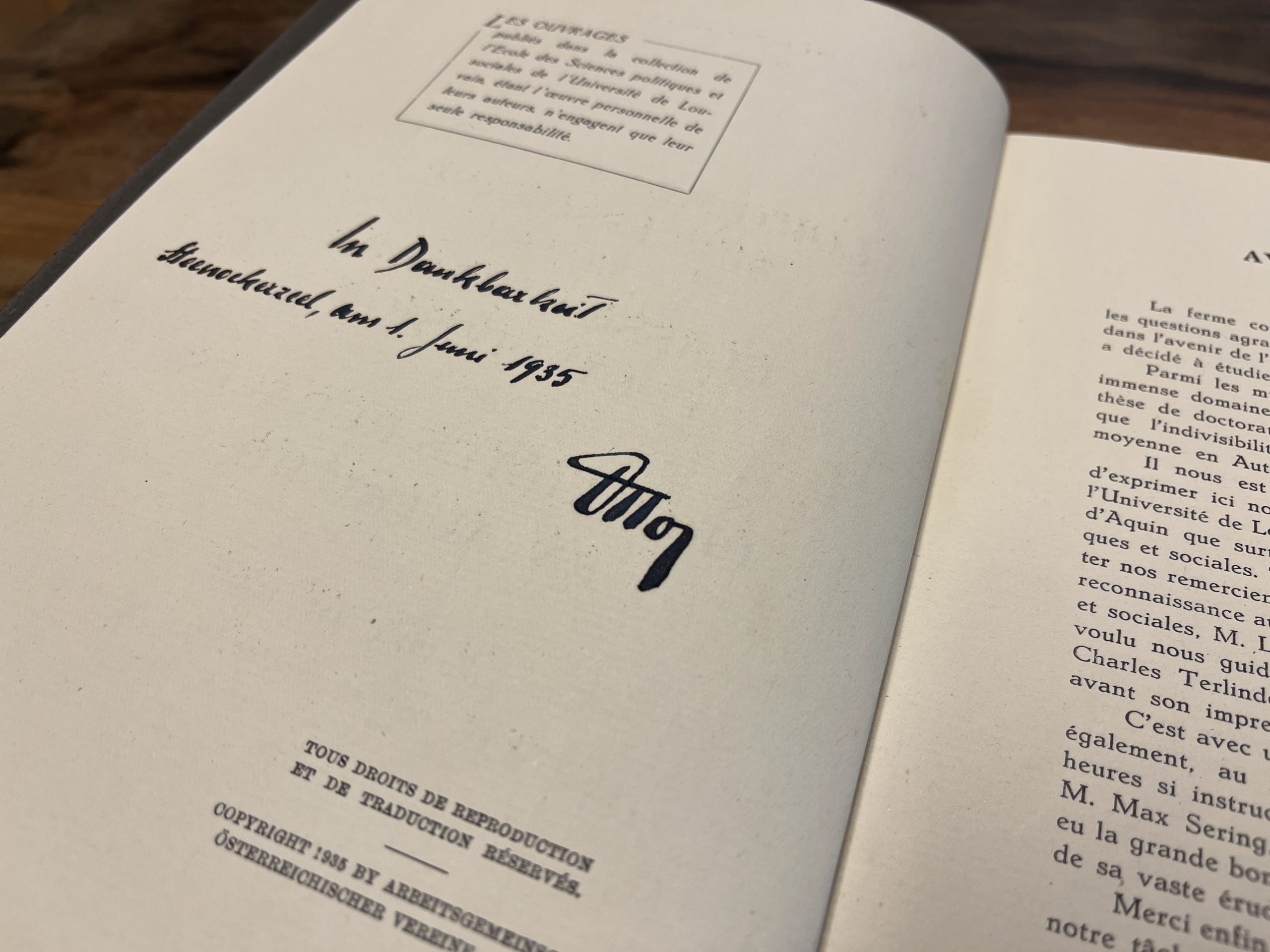

In the second part of the viva voce, Otto von Habsburg had to demonstrate his knowledge of three topics related to the subject of his dissertation. First, he had to discuss the economic developments of the Danube countries and potential forms of cooperation. Next, he addressed the concept of democracy in the new Austrian republican constitution. Finally, Otto von Habsburg was asked to provide his opinion on the reforestation plans for the Hungarian Plain and the dilemmas of the planned economy system. As the former Crown Prince later reported, he had read numerous works by Hungarian village researchers in preparation for his thesis defence.[3] To complete his dissertation and prepare thoroughly, he retired from Steenockerzeel to the coastal town of Wenduyne, in the company of Count Degenfeld,[4] where he could focus exclusively on his task. Thus, his doctoral dissertation was published and received praise from the examination committee.

The professors were also satisfied with his answers to the three topics, and the committee unanimously recommended an excellent grade. Otto von Habsburg completed his university studies with honours, passed his final examination with flying colours and received the highest grade for his thesis. Furthermore, the former heir to the throne earned the rare accolade that the assessment included the phrase ‘avec la plus grande distinction’, meaning ‘with the highest distinction’. The conferral ceremony was performed by the university’s esteemed rector, Bishop Ladeuze, after which the professors congratulated Otto von Habsburg individually. On the evening of the scholarly ceremony, the Archduke was celebrated at a banquet in Steenockerzeel, at Ham Castle. In his toast, Archduke Robert emphasised that his brother was the first Habsburg pretender to the throne to receive a doctorate in his own right. One of his teachers added that he was probably the first royal heir in the world to obtain the highest university degree in the proper way.

Otto von Habsburg’s commendation 90 years ago marked the beginning of a new era in which ancestry alone was no longer sufficient to obtain academic titles. The economic and social issues analysed by the former crown prince would continue to play a decisive role in his later career.

Gergely Fejérdy

[1] Hogyan tette le Ottó király doktori vizsgáját a louvaini egyetemen. [How King Otto passed his doctoral examination at the University of Louvain.] Magyarság, 2 July 1935, 8.

[2] L’archiduc Otto Docteur en Science Politiques et Sociales de l’Université de Louvain. [Archduke Otto, Doctor of Political and Social Sciences, University of Louvain.] La Libre de Belgique, 30 June 1935, 6.

[3] Habsburg, Ottó: Hogyan tanultam meg magyarul? [How I learned Hungarian?] Új Európa, 1962, 7, 5–6.

[4] Csonka, Emil: Habsburg Ottó. Egy különös sors története. [Otto von Habsburg. The story of a strange fate.] Munich, Új Európa, 1972, 70.