Hans Karl von Zeßner-Spitzenberg was born in Dobritschan, Bohemia, into an ancient Habsburg-loyal Czech baronial family of Luxembourg origin with many links to the imperial court. His father, Heinrich von Zeßner-Spitzenberg[1] was an Imperial and Royal Chamberlain, a landowner, and his cousin, Eleonore Nostitz-Rieneck[2] served as a lady-in-waiting to Zita of Bourbon-Parma until her marriage. Count Ledochówski,[3] riding master to the imperial children and former aide-de-camp to Emperor Charles I, was also related to the family. Count Wallis,[4] a former tutor of the last Austrian emperor, was a good friend of the family.[5] Traditionally, loyalty to the House of Habsburg and service to the monarch were important to them. Hans Karl von Zessner-Spitzenberg first met the future emperor in 1906, when Charles was stationed with the 7th Regiment of the Imperial and Royal Dragoons near Dobritschan. The Archduke was accompanied by Duke Lobkowitz[6] to the castle of the Zeßner-Spitzenberg family, where, after a short refreshment, he walked in the park with Hans Karl Zeßner-Spitzenberg, played tennis and returned to his station after dinner. In his diary, Zeßner-Spitzenberg recounts the visit as follows: “Archduke Charles made a very good impression on all of us; he was rather calm and quiet, without any pridefulness, at times perhaps a little childlike. Naturally, this visit caused quite a stir in the village.”[7]

At the time of the visit, Hans Karl von Zeßner-Spitzenberg was already a university student. He was studying law at the Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague and received his doctorate on 2 July 1909. After completing his studies, he undertook a traineeship in the administrative service of the Imperial and Royal Governor’s Office in Prague, which he interrupted for two years to study economics in Berlin. He wrote his doctoral thesis in the latter discipline under the supervision of Max Sering[8] with the title Urban Industrial Concentration and Rural Emigration in the Czech Republic, 1880-1900. In 1912, after obtaining his second doctorate, he returned to Prague and a year later worked at the Agricultural Statistics Department of the Central Statistical Commission in Vienna. In May 1918, he was appointed Deputy Minister in the Imperial and Royal Ministry of Agriculture, a post he was able to retain after the fall of the Monarchy.[9]

Shortly afterwards, in 1920, he habilitated in general and Austrian administrative law at the Hochschule für Bodenkultur in Vienna. His thesis focused on a better understanding of the living and working conditions of the rural population, and examined the balance of interests between the agricultural establishment and the wage-earners who worked for it. In his study, he formulated rather forward-looking points, compared to his time, regarding the social situation. These included the introduction of a health insurance fund for agricultural workers, the establishment of a pension scheme for rural day labourers, and the public representation of agricultural workers as a separate section in the provincial chamber of labour.[10]

The period as a university lecturer was important in his life, as he noted more than once in his diary, providing him with the perfect platform to transmit his Catholic faith and his enthusiasm for politics[11] and to promote good causes.[12]

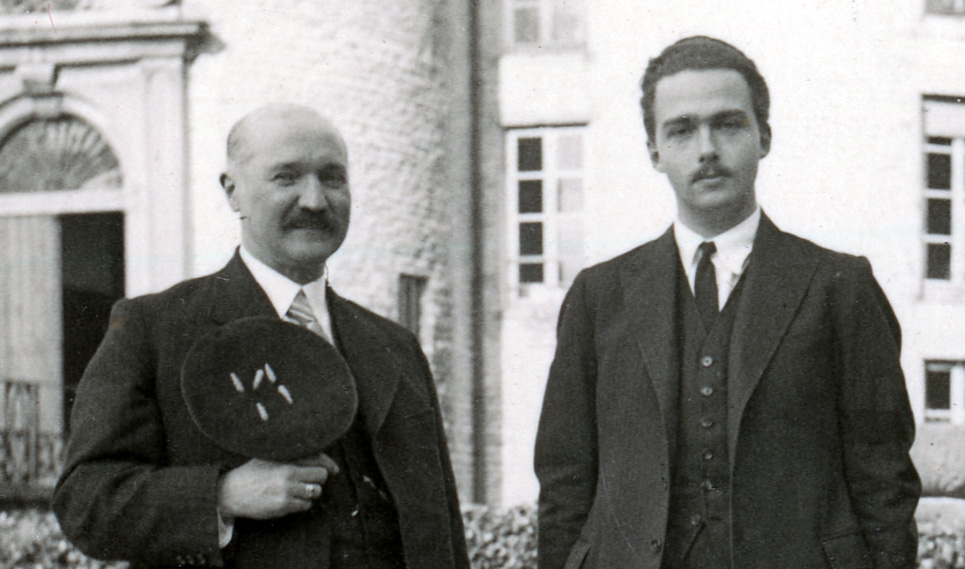

From left to right: Count József Cziráky, Count Heinrich Degenfeld, Count János Zichy, Otto von Habsburg, Hans Karl Zessner-Spitzenberg, Miklós Griger

1936, Steenokkerzeel, Belgium

Besides teaching, his other passion was helping the family of the late Emperor Charles and supporting Archduke Otto in his efforts to return to the throne. He maintained close ties with the Habsburg family throughout the difficult period following the First World War, as his biographical works on Charles I,[13] the Lequeitio period[14] and Otto von Habsburg[15] attest. On the other hand, his close connection is evidenced by his regular inclusion in the diaries on the Habsburg children, which are preserved in our Foundation. A good example of this is his visit from 11 to 21 August 1923, during which Baron Zeßner played a lot with the children and joined the family on a boat trip. [16] The visits to Lequeitio were followed by visits to Steenokkerzeel, where he was the only Austrian professor to attend Otto von Habsburg’s doctoral thesis defence in 1935.

The lives of the two families have intertwined at several points over the years. Zeßner and Otto von Habsburg worked closely together to prevent the Nazi takeover of Austria. The night before the Anschluss, on the morning of 11 to 12 March 1938, the former heir to the throne spoke to Zeßner for the last time. In their telephone conversation, Otto von Habsburg strongly advised his unconditional Austrian supporter to leave the country for his personal safety. Zeßner spent two days in a monastery on the outskirts of Vienna to reflect on the serious decision, but then returned home to his family. He reported himself to the Gestapo on the same day, but was sent home for the time being, and was only arrested on the morning of 18 March while attending Mass at the Church of St Mary of Sorrows, not far from his home. He was transferred to the provincial court on 29 April 1938, from where he was taken to Dachau on 16 July. The Austrian transports were characterised by particularly cruel treatment. During the journey, Zeßner was hit in the kidney with a rifle barrel and his injuries led to his death half a month later. It was part of the SS ritual to line up newly arrived prisoners and have them explain why they had been sent to Dachau concentration camp. Zeßner fearlessly confessed: “Because I regard faith in God and in Christian Austria under the leadership of the Habsburgs as the only guarantee of my country’s independence and autonomy.” This was enough reason for him to be transferred to the camp’s infamous isolated block 15, where he had to carry out extremely hard physical labour. On 30 July, although already severely weakened by the kidney damage and having a fever of 40 degrees, he was forced to do two hours of punishment work in the midday heat; he collapsed and died the next day in the concentration camp’s infirmary, aged 53.

Hans Karl von Zessner-Spitzenberg said goodbye to Otto von Habsburg in their last conversation with the words “On the Day of Resurrection”, implying that they would meet again upon Austria gaining independence. He did not know then that his words would eventually mean the time of the actual resurrection. The ambiguous farewell encompassed the Baron’s lifelong perseverance in fighting not only for the restoration of the Habsburg dynasty, but also for the independence of Austria and Europe.

Anett Hammer-Nacsa

Letter from Queen Zita to the widow of Hans Karl von Zessner Spitzenberg[17]

Dear, poor Baroness! Words are not needed to express how deeply I sympathise with you and your children in your grief and how much I feel your pain. In the face of such grief and pain, all human consolation falls silent; only God can give help and strength to the broken heart, the deeply wounded soul. I beseech Him most fervently for this in prayer! I also turn to the Mother of God beneath the Cross – she, the Mother of Sorrows and of Mercy, knows how deeply suffering can humble us, how torn our poor hearts can be. She will take care of you and your children – the widow and orphans of a martyr – with merciful love, and I will pray for strength and fortitude for the difficult Way of the Cross, which, in thorny abandonment, leads to a blessed eternity. My whole heart goes with you, dear Baroness, on this harrowing path, the heaviest burden of which is loneliness, and on which only complete trust in God and the thought of the heavenly bliss of the one to whom your love and your grief belong can give you the strength to go on.

During all those terrible months of suffering, my children and I were constantly with you and Baron Zeßner in our thoughts and prayers. How will he now praise the sorrows, pains and torments borne with the most glorious Christian heroism, because they brought him even closer to the throne of God, which he had already earned through his exemplary fulfilment of duty, most selfless loyalty and unimpeachable Catholicism. What an incomparable heavenly crown must have been prepared for this warrior of God and His Church. What happiness the late Emperor must have felt to be able to wait in eternity for his most faithful devotee, his steadfast friend, the staunch supporter of his family, to accompany him to the throne of God and to thank him for all that Baron Zeßner had done for the Emperor and his country throughout his life. Now they will pray together without ceasing for those who are closest to their hearts, for their loved ones and for their beloved Austria. They, whose lives are so similar in the depth of their faith, their unshakeable trust in God, their love for their family, their devotion to their homeland and their death far from it.

The Emperor, we all, and Austria with our unforgettable Baron Zeßner have lost unspeakably much. It is something we feel deeply and we know that no one can replace his help, his friendship and his loyalty. One of the many things for which I will never be able to thank him enough in prayer, is his work for the veneration of the late Emperor. No one before him had spread the understanding of my husband’s spiritual greatness, the true knowledge of what he had done for his people, as widely and as far as Baron Zeßner did. If the world and especially his homeland is finally and gradually recognising the true greatness of Emperor Charles, it is thanks to Baron Zeßner’s tireless work, loyalty and love. If there is a special blessing on devotion, then this blessing must be bestowed on him in the greatest measure. And that you, dear Baroness, and your children do not fall short of him in this loyalty is proved by what your daughter Agnes wrote on the day she was heartbroken by the news of the death which made her as much a martyr as you. May the Lord God take you, my dear Baroness, and your children into His fatherly arms and protect and guide you until the blessed reunion with your saintly deceased. In this prayer, I express my complete, immense, deep gratitude for Baron Zeßner.

Zita

(letter dated 28 August 1938)

Hans Karl Zessner-Spitzenberg cikk_Zita levél_hna_német

[1] Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Heinrich von (1839–1922)

[2] Nostitz-Rieneck, Eleonore (1886–1922). His father Johann Wilhelm Hermann von Nostitz-Rieneck (1847-1915) and Hans Karl von Zeßner-Spitzenberg’s mother Henriette Nostitz-Rieneck (1846-1926) were brothers.

[3] Ledochowski, Wladimir (1865-1933), Colonel, aide-de-camp to Charles. Ledochowski’s mother was Isabella von Zeßner-Spitzenberg (1836-1927), sister of Hans Karl von Zeßner-Spitzenberg’s father.

[4] Wallis, Georg (1856-1928), Charles’s tutor between 1894 and 1907.

[5] Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Hans Karl: Bericht an die Gestapo. Mein Leben und Streben, Wien, 1938. The author gained access to the typescript through the courtesy of descendants.

[6] Lobkowitz, Zdenko (1858-1933) was an officer in the Austro-Hungarian joint army, and from Charles’s coming of age he served as his chamberlain.

[7] Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Pius: Hans Karl Freiherr Zeßner-Spitzenberg. Ein Leben aus Glauben. Wien, [2003], 9. (Hereinafter referred to as: Zeßner-Spitzenberg (2003))

[8] Sering, Max (1857-1939) was a German economist who taught not only Zeßner but also Otto von Habsburg.

[9] Welan, Manfried: Hans Karl Zeßner-Spitzenberg. Jurist und Professor an der Hochschule für Bodenkultur. https://austria-forum.org/af/Wissenssammlungen/Essays/Recht/Hans_Karl_Zessner-Spitzenberg

[10] Welan, Manfried – Wohnout, Helmut: Hans Karl Zeßner-Spitzenberg – einer der ersten toten Österreicher in Dachau. https://austria-forum.org/af/Wissenssammlungen/Essays/Recht/Hans_Karl_Zessner-Spitzenberg1 (Date of download: 2025.01.22.)

[11] Zeßner-Spitzenberg (2003) 20.

[12] Welan, Manfried – Wohnout, Helmut: Hans Karl Zeßner-Spitzenberg – einer der ersten toten Österreicher in Dachau. https://austria-forum.org/af/Wissenssammlungen/Essays/Recht/Hans_Karl_Zessner-Spitzenberg1 (Date of download: 2025.01.22.)

[13] Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Hans Karl von: Ein Kaiser stirbt. Altenstadt, [1953]; Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Hans Karl von: Kaiser Karl. Hrsg. Erich Thanner. Salzburg, 1953.

[14] Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Hans Karl von: Die kaiserliche Familie in Lequeitio. Reiseerinnerungen eines Österreichers. Wien, 1924.

[15] Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Hans Karl von: Otto von Österreich. Wien, 1931/32; Zeßner-Spitzenberg, Hans Karl von: Otto von Habsburg im Bild. Innsbruck, 1935

[16] Habsburg Ottó Alapítvány, Habsburg Ottó Gyűjtemény, A családra vonatkozó iratok és levelezések, Naplók feljegyzések, HOAL I-1-d-32

[17] Zeßner-Spitzenberg (2003), 91–92. The letter was translated from German by Anett Hammer-Nacsa.