The Otto von Habsburg Foundation launched an event series in the spring of 2025 under the motto “80 Years of Peace, 35 Years of Democracy,” which analyses the political, economic, and social developments in 20th-century Europe, with a special emphasis on the momentous events of 1989–90. At the first conference, held on 27 March, our guests presented three German-language books on the geopolitical realities of the Central European region in the 1970s and 1980s and the margins of manoeuvre it had, shaped by the global political context.

“Who does not know the past, can not understand the present and shape the future.” – Gergely Deli, Rector of the Ludovika University of Public Service, quoted the words of Helmut Kohl, recalling the historical foundations of the thousand-year-long Hungarian-German ties, which have retained their strategic importance despite differences of opinion on current political issues.

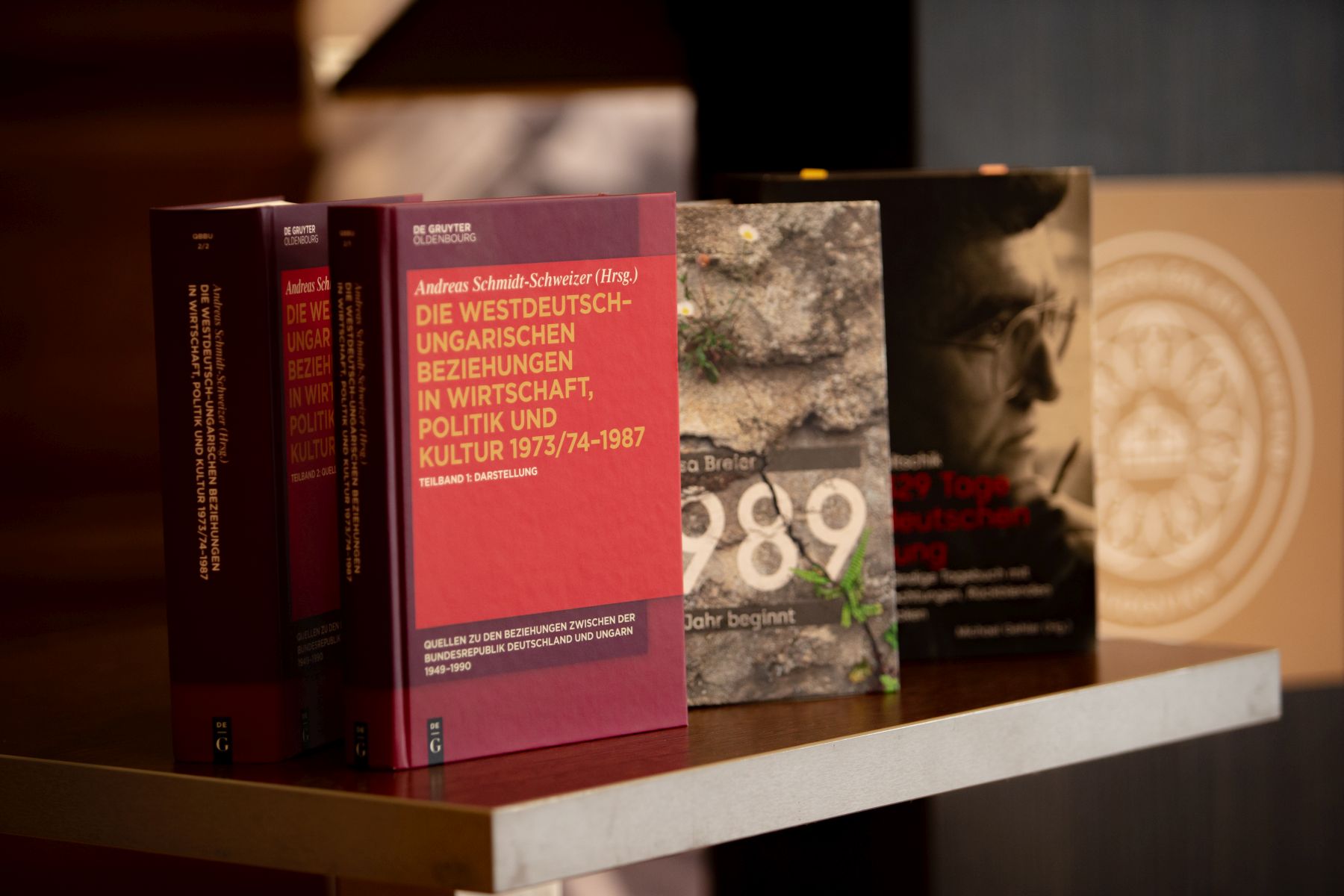

Gergely Prőhle presented the three volumes in his welcoming speech: Horst Teltschik’s Die 329 Tage zur deutschen Einigung. Das vollständige Tagebuch mit Nachbetrachtungen, Rückblenden und Ausblicken (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2025), an edition of his diary from the time, with commentary by Michael Gehler; Zsuzsa Breier’s 1989 – Das Jahr beginnt (Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2023), an essayistic memoir; and Andreas Schmidt-Schweizer’s source publication on West German-Hungarian relations (Die westdeutsch-ungarischen Beziehungen in Wirtschaft, Politik und Kultur 1973/74-1987. 1–2. De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2024).

The following discussion, moderated by Bence Bauer, Director of the German-Hungarian Institute for European Cooperation at the Matthias Corvinus Collegium, reflected on Andreas Schmidt-Schweizer’s introductory remarks. The Senior Research Fellow at the Institute of History of the HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities began the retelling of German-Hungarian relations from the 1970s, which, with its ever-renewing dynamics – the result of common traditions, complementary economic structures, shared existential interests and geopolitical factors – has led to a historical turning point. In her archival research, Zsuzsa Breier applied a narrower perspective, primarily focusing on individual destinies and unravelling them within the tapestry of three societies: East and West German and Hungarian. She noted the ambiguity of processes which, in hindsight, appeared to be determined: even as late as October 1989, the East German leadership had yet to reject the prospect of the internment of tens of thousands of politically unreliable individuals. Markus Meckel, the GDR’s last Minister for Foreign Affairs, argued that the ideal solution had been negotiation; it was a long but ultimately successful process and, therefore, required a different approach. The same applies to modern crises, and Meckel expressed criticism of the Hungarian government’s response to some of them. The panellists agreed that the Soviet attitude, which was becoming more permissive, was the decisive factor in the development of events and that the refugee issue – in German-German or Romanian-Hungarian context – merely provided the final impetus for the dissolution of the Eastern bloc.

Miklós Németh, the last Prime Minister of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People’s Republic and the first (provisional) Prime Minister of the Third Hungarian Republic, reviewed the defining milestones of history during his tenure (24 November 1988 – 23 May 1990). For him, 10 May 1989 marked the moment of the regime’s capitulation, when Károly Grósz, General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party, in a letter co-signed with the President of the Patriotic People’s Front, renounced the right to appoint and dismiss the Prime Minister and ministers. However, this was preceded by lengthy and complex developments in foreign and domestic politics, such as the February laws passed (in the one-party parliament!) on associations and unions or the personal order written by Németh to the commander of the Border Guard to dismantle the western border, which led to the Pan-European Picnic in August and the opening of the borders in September. And, of course, all the Soviet-Hungarian negotiations that were constantly taking place behind closed doors, the implementation of which was guaranteed by the mutual trust between Mikhail Gorbachev and the Hungarian Prime Minister.

In Miklós Németh’s interpretation, annus mirabilis was not a “work without an author” – referring to the Oscar-winning German filmmaker Florian Henckel von Donnersmark’s biography of the painter Gerhard Richter, Never Look Away (Werk ohne Autor) – but rather, it had actors. In addition to him, some of them were present at the conference, such as István Horváth, the former ambassador of Hungary to Bonn, and from Western Europe, Horst Teltschik, a pivotal figure of the regime change, to whom the former prime minister expressed his heartfelt gratitude on behalf of the entire Hungarian nation for his fair and selfless support spanning several decades.

Miklós Németh concluded by drawing two lessons from the events of that time. Firstly, systems based on lies and principles alien to human nature underestimate people’s memory. The second is that change should not be feared – if it is truly necessary and the opportunity presents itself. Describing himself as an optimist, he considered that a Hungary committed to democracy and the rule of law will always remain a respected part of Europe.

Subsequently, Michael Gehler, Director of the Institute of History at the University of Hildesheim, outlined the circumstances surrounding the creation of the volume he edited. Then, the author, Horst Teltschik, former Deputy Head of the Chancellery, addressed the audience. Teltschik, who has been an interlocutor with the world’s leading politicians for forty years, described the process of European unification as economically driven, while recognising the political motivation behind the German credit policy that, in part, led to the regime change. “National interests must still be considered within the framework of European integration,” he cautioned. “Chancellor Kohl’s Henry Kissinger”, as he was commonly called, referred to the guiding principle of German-Hungarian relations as always having been a negotiated approach between the parties concerned, which, in his view, is the only perspective that can create mutual satisfaction in the long term – and which, regrettably, is precisely what is being undermined in the management of contemporary conflicts, according to Teltschik.

Photos by Zoltán Szabó