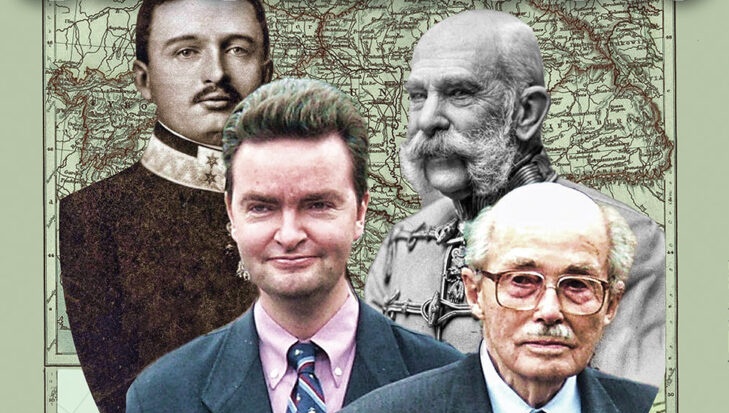

Regarding the relationship between the last Hungarian heir to the throne and the Jews, first of all, his active contribution to the rescue of people in German-occupied France should be mentioned. The adventurous events in which the last Hungarian heir to the throne sometimes risked his own life certainly validate the lines he wrote and said in his statements about the Jewish community during his long career.

Otto von Habsburg, who was not only born into the dynastic tradition, but also tried to reflect on it in his work as a historian and politician, dealt with the historical role of the Jews in the formation of the Habsburg Empire, especially during the reign of Charles V. In his book Die Reichsidee (1986), or The Imperial Idea, in which he analyses the historical precedents of European integration, he devotes a special chapter to the question entitled “Our Jewish Roots”. He explains that in the biblical tradition it is impossible to separate the Old and New Testament elements. Reviewing the historical context, he acknowledges that during the reign of his own ancestors, the attitude towards the Jews varied, from granting full equality to open discrimination and pogroms, the latter especially in the eastern provinces. On the subject of Jewish emancipation in the 18th and 19th centuries, he draws an interesting parallel between Jews and aristocrats as “supranational elements” who were easy to declare enemies during the advance of nationalism. He highlights the heroism and sacrifice of soldiers of Jewish origins during the First World War and the crucial role of Jewish writers in creating a widespread understanding of the role of “old Austria” in uniting the peoples. Here he specifically refers to Joseph Roth, who in the 1930s not only wrote excellent novels that nostalgically recall the Monarchy, such as The Radetzky March or The Emperor’s Tomb, but also, as an active legitimist in close contact with Otto in Paris, tried to promote the return of the heir to the throne to Austria. This notoriously came to nothing, with Nazi Germany eloquently calling the invasion of Austria in 1938 “Operation Otto”.

In the context of Otto von Habsburg’s recent relationship with the Jewish community and his image of the Jewish state, our Foundation’s archives preserve an exchange of letters between Ferenc Kenedy, a former Budapest lawyer and editor of the newspapers Új Kelet and Hét, published in Tel Aviv, and the last heir to the Hungarian throne. In his German-language letter to Otto, dated 28 July 1959 in Tel Aviv, Kenedy – who adress Otto as “Kronprinz”, or Heir to the Throne, and whose style retains the tone of “loyal subject” throughout the letter – asks him eight questions. These mainly concern the role and significance of the State of Israel, the possible actuality of the Jewish question, the relationship between the Habsburg dynasty and the Jewish community in Central Europe, but Kenedy is also interested in Otto’s opinion of Miklós Horthy, his daily activities and the possible changes in world politics. The journalist concludes by asking: “What message is Your Majesty sending to the Hungarian Jews in Israel who were once subjects of the Monarchy?”

Otto replies by return of post, responding in detail to the questions asked. He describes how he has always followed the formation of the Jewish state with great interest, as the modern form of the Zionist idea was born “in our Danube Valley homeland”. The most important lesson, he writes, is that with faith and determination, it is possible to achieve what previously seemed impossible. This shows the misleading nature of the respective realism that only takes into account the tangible assets. In the light of Otto von Habsburg’s writings, it is not difficult to read from these lines the message of the importance of faith in the overthrow of the communist system. He admits that he has been to Israel incognito, but he is determined to return. He is primarily interested in the system that allows different cultures to coexist, and the fact that socialist and liberal ideologies, state and economic organisation practices seem to cohabit peacefully there.

After the fall of Nazism, Otto von Habsburg saw no threat of excessive nationalism anywhere on the continent. Observing “the signs of the times”, he concludes that “the so-called Jewish question is losing its relevance”. Since – and here he looks back to the Monarchy with almost a sense of nostalgia – along the Danube it was once proven that equality before the law is possible regardless of origin or religion. The head of the former royal house says that the international character of the Jews of the Danube region explains that “they understood the deeper meaning of ‘Donaureich”, which the “dynasty” always reaffirmed with great understanding and recognition of the rights of the Jews. In addition to mentioning the period of Franz Joseph I, he emphasises the excellence of Vilmos Vázsonyi, the “associate” of his father, King Charles IV, whose loyalty to him was an example of the faithfulness of the subject even in difficult times. (…)

The full article will be available on www.szombat.org