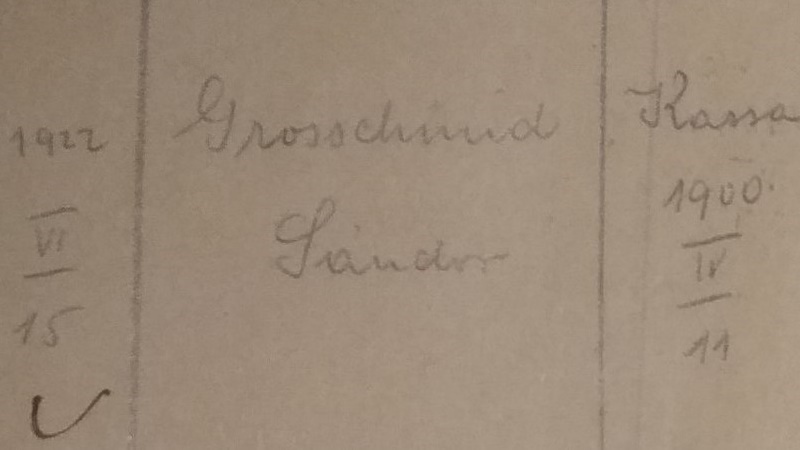

In the early afternoon of June 13, 1922, the first client of the Hungarian Consulate General in Berlin was a 22-year-old university student. He arrived because of a citizenship case, bringing all his available documents with him. After a short wait, he was greeted by an office clerk and then led to one of the upstairs offices, where the clerk recorded his data with the 27th serial number in a diary of optants. Sándor Grosschmid, who had been studying in Germany for almost three years at the time, became a Czechoslovak citizen under the Trianon decision. However, the peace treaty also provided an opportunity to declare the retention of his Hungarian citizenship in a Hungarian office or mission abroad within a year of June 26, 1921. However, the opting, ie the retention of Hungarian citizenship, meant that he had to leave his former place of residence, in the case of Grosschmid, Kassa – and Czechoslovakia. At that time, the young man had been living away from his hometown for several years, which, along with his family, had been moved to the other side of the border. Thus, he had to decide whether it was officially Košice or Budapest for him?

Hundreds of thousands of people, most of whom fled or relocated from successor states, applied to retain their Hungarian citizenship in the year specified in the peace treaty. In addition to them, tens of thousands more, living in other countries in Europe or overseas, faced becoming citizens of a new country against their will. And what was natural until then, now had to be applied for with official documents in their hands.

In June 1922, ninety-one persons applied to retain their citizenship in Berlin. Although thousands of applications could have been submitted in that specific year, we only know the data for June. The Berlin optants were mostly people, who originally resided in a detached area, but before Trianon moved to a city that remained in Hungary or to the German capital.

Sándor Grosschmid went to the consulate in Bülowstrasse barely two weeks before the deadline, with a birth certificate, a baptism certificate and a residence certificate in his bag. As a place of residence, he gave the address of a tenement house at 12 Xantanerstrasse in the Wilmersdorf district, less than a half-hour walk from the embassy. He also dictated his religion and marital status and then said goodbye to the embassy secretary. Leaving the building he could have met another optant, the 58-year-old lathe machinist István Kutenics, who was renting a room in the Neukölln district and whose name is written after Grosschmid’s in the record.

The consulate accepted Grosschmid’s application two days later, but Kutenics had to present his certificate of residence in addition to his baptism certificate in order for his case to begin. For this reason, only the application of the university student was forwarded to the Hungarian Ministry of the Interior that day.

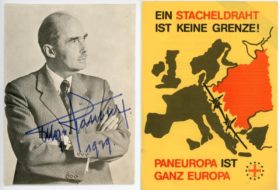

Grosschmid, soon as Sándor Márai, of course remained a Hungarian citizen, but a year later as a married man he left Berlin, which he considered a foreign city forever. The fate of Kutenics’s application is unknown – the only certain thing is that in 1927 he was already working away from Berlin in a factory in Roubaix.

István Gergely Szűts

The original Hungarian text can be read on the webpage of the Trianon100 Research Centre in its full length.