Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn was born into a Catholic Austrian family of intellectuals. His exceptional linguistic talent became evident early on: he was able to express himself verbally in eight languages, including Hungarian, Russian, and Japanese, and read in eleven more.[1]

At sixteen, he was already writing articles for The Spectator in London. He studied law at the University of Vienna, then came to Budapest at age twenty and attended political science classes at a university in the Hungarian capital. In 1930 and 1931, on assignment for the Hungarian newspaper Magyarság, he visited the Soviet Union twice; he reported his experiences in a series of articles, and on his return, he gave lectures.[2] His writings appeared in the following years on the pages of Catholic newspapers such as Korunk Szava and Magyar Kultúra. His sole Hungarian-language book to date was published at this time—not surprisingly, given its subject and spirit—in the book series of the magazine of the New Catholic Movement[3], which was followed by around half a dozen foreign editions. From 1935, he attended theological courses in Vienna while pursuing his doctorate in political science, which he defended in Budapest in 1936.[4]

Between 1937 and 1947, he was a teacher in the United States. As a journalist, he experienced the Civil War in Spain. At the war’s end, he worked at Chestnut Hill College in Philadelphia, where John Lukacs succeeded him as dean upon his return home. In 1947, he settled with his family in a village near Innsbruck, but without breaking with his former way of life. In the following decades, he travelled the world, visiting some 80 countries on five continents, many of them several times, and all the states of the USA.

In 1952, with the publication of his work Liberty or Equality in English, unanimously considered by his critics as his magnum opus, he immediately became an inescapable figure in the conservative camp forming overseas. As Edwin J. Feulner, later president of The Heritage Foundation, recalled the intellectual encounter: “I read Liberty or Equality by Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn in 1959 when I was a young man, which proved to be one of the most formative books of my life.”[5]

Leddihn argued that the two concepts in the title are incompatible: the more widespread the prevalence of democratic principles in a society—when a community becomes a mass democracy—the greater the risk that the majority opinion will suppress minority voices and interests. Democracy, by creating equality of rights, inevitably has political, cultural and ultimately, ethical consequences—and its egalitarian characteristics bring it into conflict with the values that individuals or social groups perceive as expressions of freedom. The author sought to situate the problem in the domain of political trends, governmental forms, and schools of intellectual history. In the concluding chapters of the book, he examined the impact history of Protestantism on the region of the source of national socialism.

Along with Russell Kirk’s 1953 book, The Conservative Mind, it was perhaps this work that most inspired American political thought in the following decades, paving the way for the great political turn of the late 1970s (Kirk wrote the foreword to the 1993 edition of Liberty…). In 1955, William F. Buckley Jr. invited Leddihn to join the fledgling National Review, a working relationship that lasted with the weekly conservative journal for more than three decades.

This is how he described his wide-ranging activities in the 1960s:

HOAL176

His network of contacts with intellectuals is comparable to that of Otto von Habsburg and, in many respects, coincides with it. The correspondence between the two spans nearly half a century. In addition to the American thinkers already mentioned, he was friends with Europeans or eminent figures with a European background, such as Friedrich von Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke, Alexander Rüstow, and Ernst Jünger. He participated in meetings of the Mont Pelerin Society from its foundation in 1947; in the 1980s and 1990s, he (also) worked as a research fellow at the Acton Institute and the Mises Institute.

His relationship with Otto von Habsburg

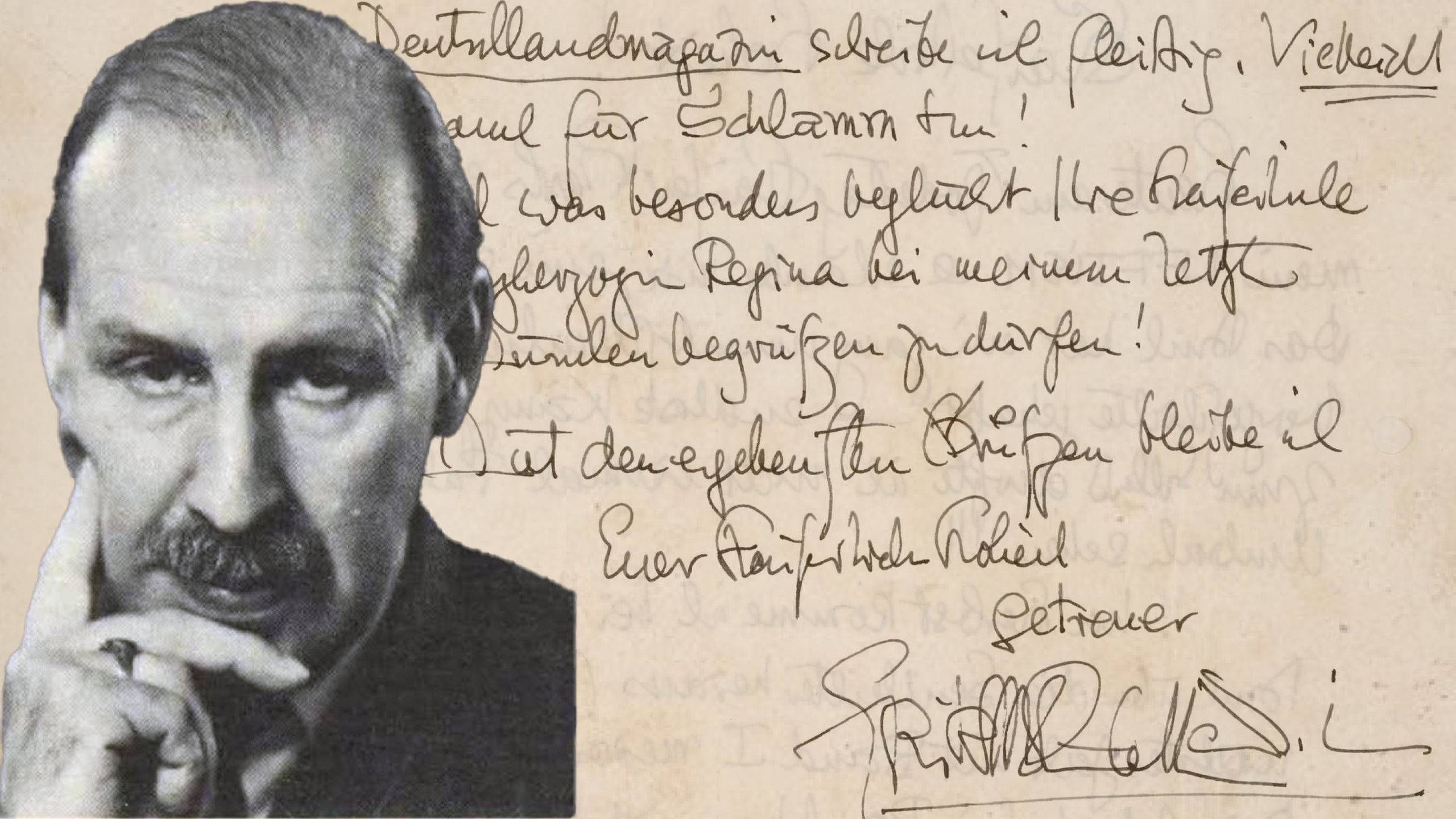

A knight who could trace his lineage back to the Middle Ages, Kuehnelt-Leddihn, born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, remained faithful to the ideal of monarchy all his life. The elements of Austrian Catholicism, which emphasised the transcendent origin of the kingdom, promoted aristocratic government based on the power of the few and maintained the need for universality, (might have) seemed anachronistic even in the 20th century, yet in his ideological framework, they formed a coherent, harmonious whole. Therefore, his sympathy for the last heir to the imperial throne and his adherence to Otto von Habsburg’s principles of the spiritual and political unity of the European nations on Christian grounds is understandable. Our Foundation preserves the exchange of letters between the two men from 1953 to 1998. They convey a perfect identity of views, a camaraderie and friendship, and a close nexus of their families. Below is a piece of their correspondence, put down on paper in Leddihn’s brisk handwriting:

HOAL175

Their professional association became, if possible, even closer in the 1970s, when Leddihn regularly contributed to the periodical Zeitbühne and, from 1980, its successor, Europa.

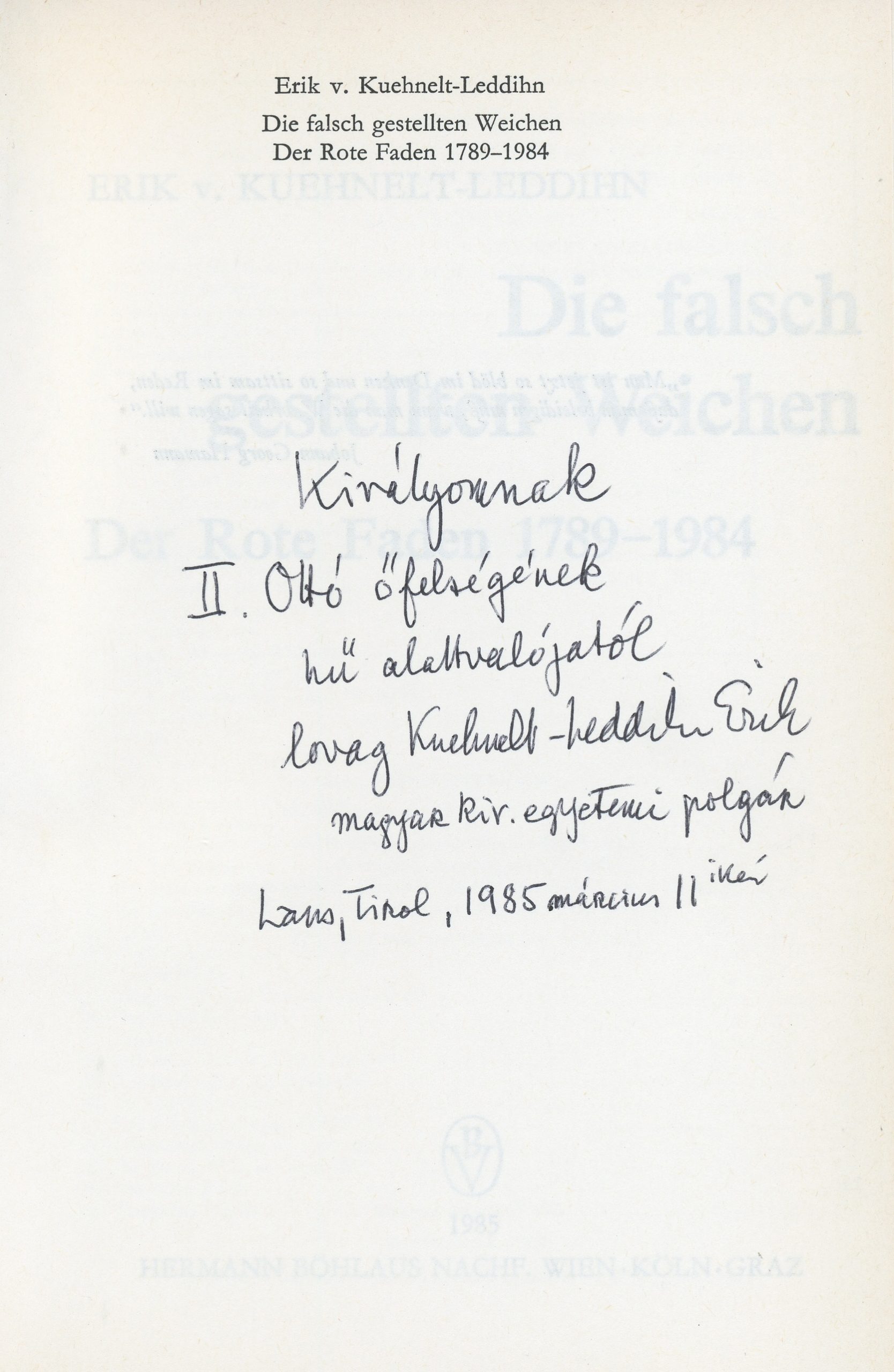

In addition to the above, our collection includes a few volumes dedicated to Otto von Habsburg in the distinctive letters of the author. Some of these are written in Hungarian:

[Transcription: To my King, His Majesty Otto II, from his loyal subject, the Knight Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, a Hungarian Royal University fellow. Lans, Tirol, 11 March 1985.]

He remained active until the end of his life, culminating in a monumental, thousand-page autobiography.[6] Three of his most influential books—The Menace of the Herd, written under the pseudonym Francis Stuart Campbell during the war, Liberty or Equality, and Leftism—are all available online.[7]

His reception in Hungary

For decades after the war, his name did not appear in print in Hungary, and only readers of emigrant newspapers (Új Európa, Mérleg, Bécsi Napló) could encounter his writings in Hungarian-language publications. Although he gave three lectures in Budapest in 1990[8], in the fever of the regime change a few days after the formation of the freely elected Hungarian Parliament, these went without resonance. His oeuvre is slowly being unearthed; Gábor Megadja and Zoltán Pető deserve special thanks for their research.

We hope this article has piqued readers’ interest in the less-known life and work of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn. As we process the material in our archives, we will soon publish further details of his relationship with Otto von Habsburg and his contribution to European and American political science and the history of intellectual thought.

Ferenc Vasbányai

Recommended bibliography

Gábor Megadja: Szabadság vagy demokrácia? A modern demokratizmus és a totalitarizmus problémája Kühnelt-Leddihn politikai filozófiájában. [Freedom or Democracy? The Problem of Modern Democratism and Totalitarianism in the Political Philosophy of Kühnelt-Leddihn.] Kommentár, 2008, 1, 64–76.

Idem: Erich von Kühnelt-Leddihn és Amerika. [Erich von Kühnelt-Leddihn and America.] Századvég, 2011, 3, 127–137.;

Idem: A demokrácia liberális kritikája. 1–2. Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Kolnai Aurél, Hannah Arendt és Eric Voegelin. [A Liberal Criticism of Democracy. 1-2. Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Aurél Kolnai, Hannah Arendt and Eric Voegelin.] Magyar Szemle, 2017, 1/2, 60–65. and 3/4, 55–63.;

Tamás Nyirkos: Szekularizáció és politikai teológiák. [Secularism and Political Theologies.] Századvég, 2017, 4, 109–122.

Zoltán Pető: Egy reakciós „liberális” a 20. században. Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn politikai filozófiája. [A Reactionary “Liberal” in the 20th Century. The Political Philosophy of Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn.] Ludovika Kiadó, Budapest, 2021.

[1] The sources are contradictory in terms of the exact numbers.

[2] These trips were not without dangers, yet an assassination attempt was made against him in Budapest on the Danube bank (Magyarság, 18 October 1930, 11.).

[3] Jesuiten, Spiesser, Bolschewiki. The Gates of Hell. An Historical Novel of the Present Day. Translated by I.J. Collins, Sheed & Ward, 1933.

[4] His dissertation was entitled Anglia belső krízise [Britain’s internal crisis].

[5] The quote is written on the back cover of the 1993 edition.

[6] Weltweite Kirche. Begegnungen und Erfahrungen in sechs Kontinenten 1909–1999. Christiana-Verlag, Stein am Rhein, 2000.

[7] Francis Stuart Campbell: The Menace of the Herd or Procrustes at Large (Bruce Publishing, Milwaukee, 1943), Liberty or Equality. The Challenge of Our Time (Caxton Printers, Caldwell, Idaho, 1952), Leftism: from de Sade and Marx to Hitler and Marcuse (Arlington House, New Rochelle, New York, 1974; a second edition with the revised subtitle: Leftism Revisited: from de Sade and Marx to Hitler and Pol Pot. Gateway, Washington D.C., 1990).

[8] He spoke about Europe’s mission at the Austrian Institute on 8 May, about Luther at the Raday Institute two days later, and on Marx at the Institute of History of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on 14 May. (Magyar Nemzet, 8 May 1990., 8.).