“I appreciate your giving National Review a good part of the credit. You deserve a major share of it yourself, for you have given quality and style to the conservative renaissance.” These words concluded a December 1961 letter penned by the already prominent William F. Buckley Jr. (1925–2008) to Otto von Habsburg. In the same correspondence, Buckley reflected on American political developments and the country’s growing ideological tensions, noting with concern that the media paid disproportionate attention to the radical fringes of the political right. To some extent, the very same letter also anticipates the debates that would later surround Buckley’s legacy: his efforts to unify a diverse conservative movement around a central gravitational axis – bringing moderates and radicals alike together – continue to inspire both admiration and controversy. While many celebrate him as a defining figure of mainstream conservatism, others remain more critical, at times portraying him – even if somewhat exaggeratedly – as a pathfinder of Trumpism. That said, this essay is less ambitious and obviously does not aim for a comprehensive political or intellectual and historical evaluation of Buckley’s oeuvre. It merely seeks, from the perspective of Otto von Habsburg – and thus inevitably in a somewhat subjective manner – to recall certain elements of Buckley’s work through a few selected episodes, as well as some significant moments of his personal relationship with our namesake.

“Politics is my vocation, not a part-time pursuit.”

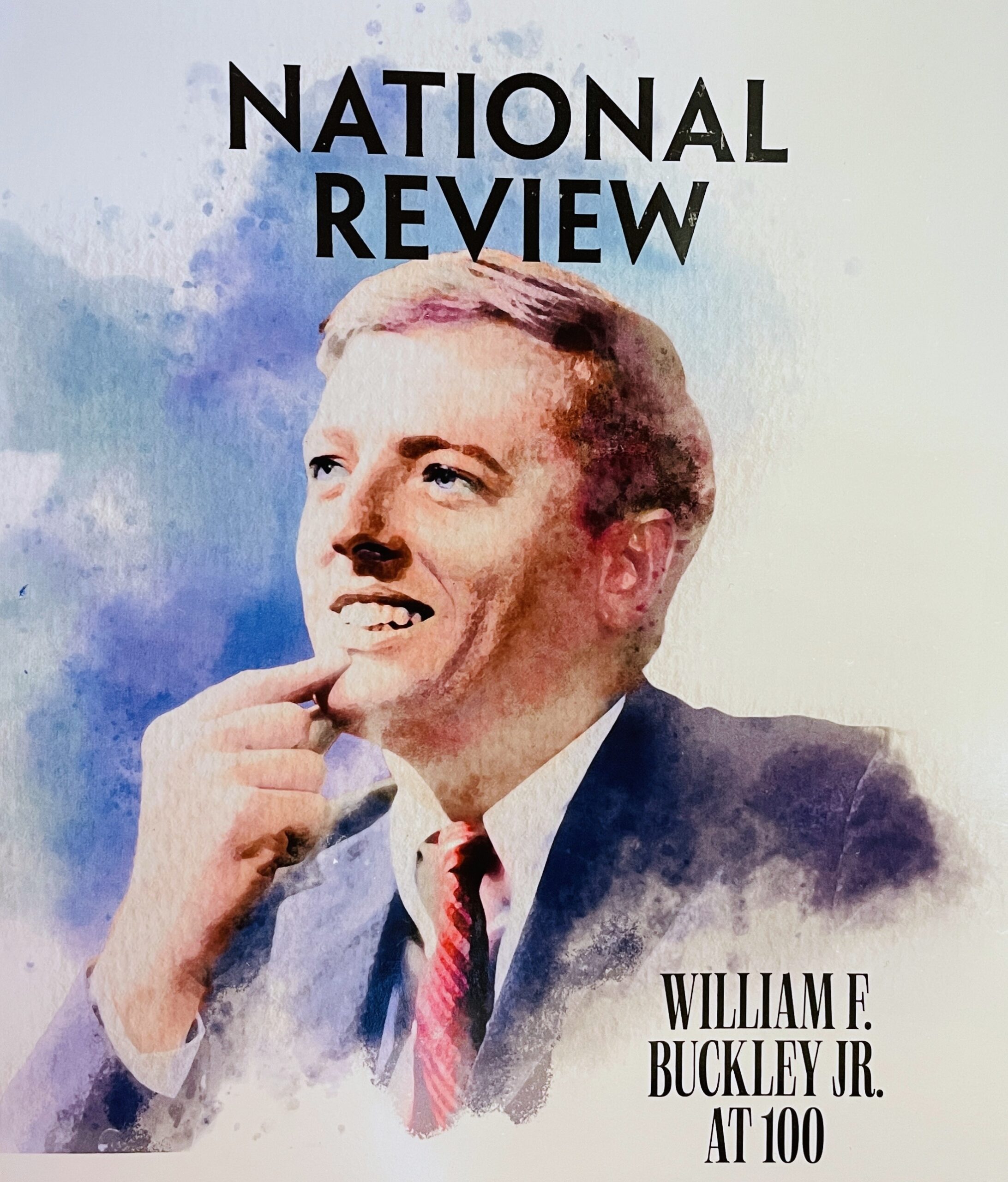

William F. Buckley Jr. was born in 1925 into a wealthy family with a profound commitment to public affairs. His upbringing was profoundly shaped by his father’s strong anti-communism, his mother’s deep Catholic faith, and the family’s cosmopolitan outlook. From an early age, he developed an interest in European culture and history and, due to the family’s frequent relocations, became fluent in both French and Spanish – though he later wrote to Otto with surprising modesty about these proficiencies – while also mastering English, which, by his own account, he had only begun to speak at the age of seven, nevertheless soon becoming a true virtuoso of the language.

Buckley first made his mark on the public stage with the publication of God and Man at Yale, released shortly after he completed his university studies. In this book, he sharply criticised the academic world – particularly the political biases of elite universities – the marginalisation of religion in higher education, and the anti-capitalist perspectives prevalent in textbooks. The volume, in response to these issues, articulated a vision that combined a commitment to conservative values with support for free-market economic principles – a vision that would continue to guide his public engagement and help shape the character of post-war American conservatism.

Alongside tirelessly editing the journal he founded, National Review, and hosting the long-running television debate program Firing Line from 1966 to 1999, he proved to be extraordinarily prolific as both a nonfiction and fiction writer. In fact, he was a true Renaissance man, excelling not only on the keyboard of the typewriter but also on those of the piano and harpsichord, while avidly devoting himself to skiing and sailing. His profound appreciation for classical music, particularly Johann Sebastian Bach, is prominently displayed in his choice of the dynamic third movement of Bach’s Second Brandenburg Concerto in F major as the opening theme for Firing Line. Yet he was not merely an enthusiastic listener: encouraged by a former college classmate and friend, the renowned performer Fernando Valenti, Buckley became a skilled interpreter of the composer’s music, occasionally giving public performances of Bach’s works. He even devoted several episodes of his public affairs programme to the Baroque master and in 1985 wrote an insightful piece commemorating the 300th anniversary of the composer’s birth.

In this essay, he confesses his deep appreciation for Bach’s musical corpus, which, in his view, reveals the eternal and unchanging truths of human existence while providing both aesthetic pleasure and theological insight. The closing passages, however, move beyond these Albert Schweitzer – and Karl Barth – influenced interpretations, subtly revealing broader dimensions of Buckley’s own political thought. The birthday homage demonstrates that, for him, the realms of culture, society, and politics do not exist in isolation but form a closely interwoven, organic whole. From this perspective, democracy, freedom, and the rule of law are not merely political constructs; they are living resources, integral and breathing components of the Western cultural heritage, demanding constant cultivation and care. Consequently, public life cannot be reduced to a mere exercise in power, nor can its institutions become prey to political opportunism; rather, their functioning must be aligned with the cultural and moral traditions of the communities they serve.

Conservatives of the world, unite!

One of the clearest articulations of his own political credo is found in the portrayal of the fictional CIA agent Blackford Oakes. Buckley’s favourite operative is libertarian in that he is fundamentally distrustful of the state; at the same time, he is conservative, convinced that the preservation of Western values may, if necessary, justify the use of nuclear deterrence.

This way of thinking naturally resonated within the European milieu shaped, in part, by Otto von Habsburg, which regarded the defence of traditional order, stability, and the broader values of classical Western civilisation as equally self-evident as the protection of individual liberty, the free market, and the classical liberal principles that constrain the often Leviathan-like power of the state.

It is therefore no surprise that Buckley came to the attention of European conservatives as early as the 1950s. His 1954 book, McCarthy and His Enemies, was published in German in the same year as the English release by the Abendländische Bewegung, reaching this audience immediately, while his first meeting with Otto von Habsburg took place at the 1958 Madrid congress of the European Documentation and Information Centre (Centre Européen de Documentation et d’Information, CEDI). A few months later, Otto was already a guest at Buckley’s home in New York. The connection was encouraged by one of the leading figures of the post-1945 Hungarian émigré community, Tibor Eckhardt, who wrote to Otto in the spring of 1959: “For my part, I am extremely pleased that Your Highness accepted Buckley’s invitation to dinner. While the National Review cannot in every respect be considered conservative on economic and social questions, it reaches the highest European standard in matters of foreign policy and values.”

The diversity recognised – and in some respects regarded with caution – by Eckhardt was no accident. As George H. Nash and Lee Edwards, in their monumental treatises of modern American conservatism, have shown, the movement grew out of three intellectual currents that were, in many ways, difficult to reconcile: the libertarian-leaning, the anti-communist, and the traditionalist factions. This internal diversity presented both opportunities and challenges, as the differing principles and priorities were not easily accommodated within a coherent political programme.

The programme championed by Buckley, and labelled as “fusionism”, sought to reconcile these strands, allowing conservatism to gain broader social support while preserving its diversity and public legitimacy. Yet the success of this ecumenical approach was far from certain. On the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of Firing Line, Henry Kissinger candidly admitted that he himself had not believed that the ambitious plans with which Buckley had embarked on this “crusade” would succeed and exert such a lasting influence on American politics.

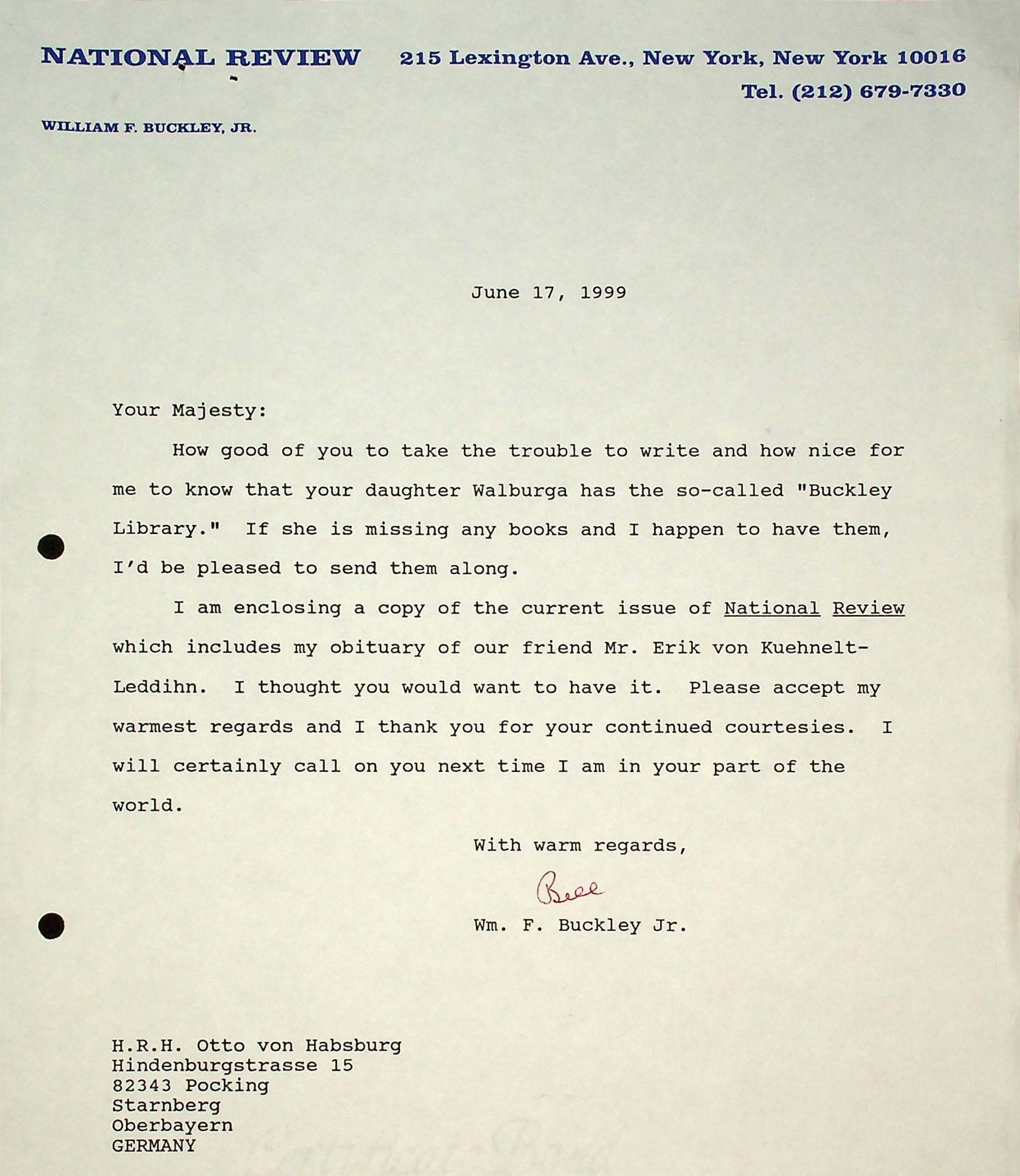

His influence, however, extended far beyond the borders of the United States, as his work played an important role in shaping a “conservative international” and a shared political vocabulary. Moreover, the organisational model of the National Review and its role in influencing public opinion served as a key reference point for the European right, demonstrating how a persistently and consistently built social base could provide a counterweight to leftist dominance. Indeed, the founding of the journal, Zeitbühne (1972–1979) by Buckley’s former editorial colleague William S. Schlamm (1904–1978) would likely not have been possible without the American example and inspiration, as well as the opportunities and resources provided by transnational conservative networks. Personal overlaps also developed between the contributors to the two magazines, as many of the National Review’s prominent writers – who were themselves key nodes in transatlantic conservative networks, including Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn (1909–1999), Thomas Chaimowitz (1924–2002), and Thomas Molnar (1921–2010) – regularly published in the pages of Zeitbühne.

„Konservativ – aus Freude am Leben”

For Buckley, Otto von Habsburg was not merely an accomplished politician but the par excellence European, embodying all that he most valued in the continent’s enduring traditions. In turn, our namesake saw in the witty, sharp-minded, and charismatic publicist a politician who consistently championed Russell Kirk’s “Permanent Things”, possessed a clear political vision, and, at the same time, could mobilise broad segments of society.

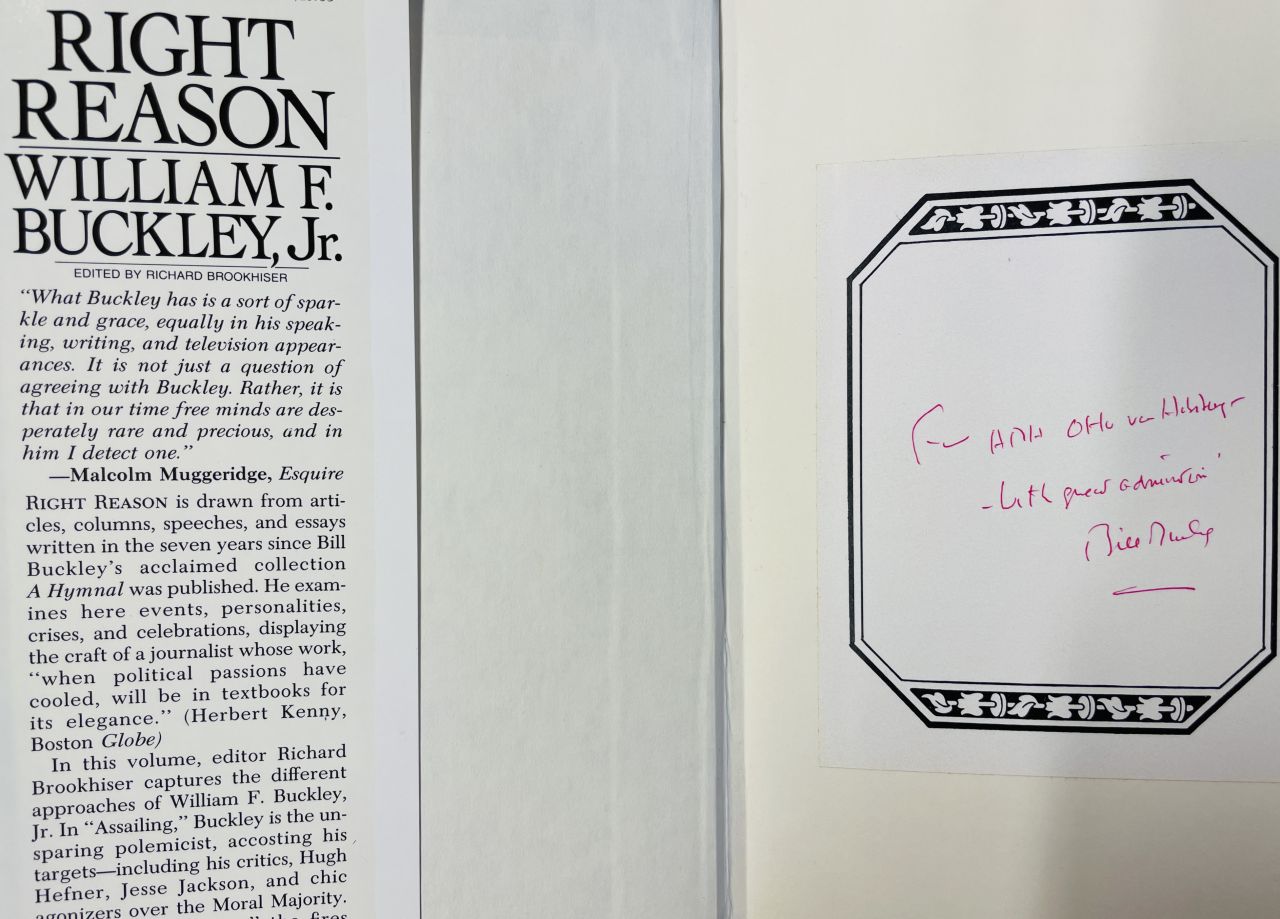

Their friendship is documented in nearly three hundred pages of correspondence preserved in our Foundation’s archives, yet Otto von Habsburg also appears among the National Review’s contributors and participated twice on the television programme Firing Line. The letters reveal not only candid discussions of European, American, and global political issues – Habsburg, for instance, did not share the National Review’s strong opposition to De Gaulle – but also that the Archduke was a passionate reader of Buckley’s novels, written during his annual creative retreats in Switzerland combined with skiing. A fan letter written after reading Stained Glass, however, was more than an expression of personal enthusiasm; it also conveyed a clear political message.

Set against the tense backdrop of the Cold War, the novel follows the CIA agent Blackford Oakes, who is assigned the delicate mission of infiltrating the circle of the rising West German politician Axel Wintergrin. The charismatic and popular count’s political ambitions – including the prospect of uniting the two Germanys – threaten the fragile political and military equilibrium of Europe, and his ascent to power must be carefully forestalled. The story not only immerses the reader in the era’s political dilemmas and Oakes’s personal quandaries but also unfolds an interwoven narrative that runs alongside the main plot. In this thread, Wintergrin undertakes the restoration of a family chapel, and it quickly becomes clear that the energy he pours into this project transcends mere bricks and mortar: it is an act suffused with symbolic and communal significance, reflecting the preservation and renewal of shared cultural and national values.

Reading the novel inspired Otto von Habsburg to articulate his own reflections in a letter. He argued that public life retains its vitality and humanity only when individuals devote time and energy to nurturing enduring values – whether literally, as in the careful restoration of chapels, or metaphorically – and do so with genuine commitment. He emphasised that politics must never become “cold, bureaucratic, and humourless,” since it – echoing Buckley’s interpretation of Bach – touches a deeper reality that cannot be entrusted solely to technocrats. Politics, he insisted, requires balance, openness, and a certain humanist sensibility. This was not a dismissal of expertise – both Buckley and Habsburg held knowledge in the highest regard – but a caution against what Buckley’s mentor and National Review co-founder, James Burnham, termed the rise of the “managerial class.” True competence, they argued, serves the common good only when it is paired with moral integrity and a sense of communal responsibility.

Lee Edwards, in his biography (William F. Buckley Jr. The Maker of a Movement) published two years after Buckley’s death in 2008, described him as the “St Paul of the conservative movement”. Unlike some of Buckley’s close nexuses – such as Whittaker Chambers, the former Soviet agent who regularly contributed to the National Review, or the aforementioned William Schlamm, who began his career at the German Communist paper, Die Rote Fahne – Buckley required no Damascene conversion. Yet the analogy is apt, for he served as a mediator and organiser without whom American conservatism would scarcely have become the defining intellectual and political force it was in the latter half of the twentieth century.

“I just want to tell you personally that I often think of one of the great Americans I have met, of a fighter for freedom, for decency, for our faith and for our hope in the future,” wrote Otto von Habsburg in a letter to Christopher Buckley, the son of the American publicist. This sentence perfectly captures that, for Buckley – as for Otto – conservatism was not merely an ideological fig leaf to serve political ends, but a profound and deeply personal commitment. Aus Freude am Leben – rooted in the joy of life.

Bence Kocsev