70 years ago, on Tuesday, May 9, 1950, at 6 pm two hundred journalists crowded the embellished Salon d’Horloge hall of Quai d’Orsay in anticipation of a hastily announced foreign ministerial press conference. The head of French diplomacy, Robert Schuman, only announced the news in the early afternoon that he intended to make an important declaration, hence only journalists based in Paris could appear at the event. No one from the radio or television was present, and not a single photographer was invited, thus the photos published from the event—used to illustrate the announcement—were taken on 20 June 1950, one month later, at the opening of negotiations for the Schuman Plan.[1]

Indeed, the French Foreign Minister announced in the evening of May 9 the idea bearing his name proposing the Western European coal and steel production to be placed under international supervision. The plan, which created the European Coal and Steel Community (the so-called Montane Union), was adopted a few hours before the press conference as the last item on the cabinet meeting’s agenda, without any detailed exposition of the text, on the proposal of some ministers close to Robert Schuman[2]. It was the first organization based on supranational principle to become one of the cornerstones of the European integration process. The proposal, drawn up by the team of Jean Monnet, the head of the French Plan Commission, first caused great surprise and even confusion, but the positive attitude of the states concerned, in particular that of the Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany, Konrad Adenauer, the Italian Prime Minister, Alcide de Gasperi, together with the external support from the United States, enabled it to be implemented quickly. The European Coal and Steel Community, with which the process of integration leading to the creation of the European Union began, was officially launched on July 23, 1952. The success of the plan and the ideas it represents is reflected in the fact that the date of its announcement was declared Europe Day by the European Council in 1985.

(left to right) Robert Schuman, Alcide de Gasperi, Dirk Stikker, Paul van Zeeland,

Konrad Adenauer, Joseph Bech

(Source: European Parliament, Multimedia)

The news of the French Foreign Minister’s declaration of May 9, 1950, of course, reached Otto von Habsburg, who lived in Paris at that time. Robert Schuman’s thoughts on Europe were not entirely unfamiliar to the former heir to the throne, as they knew each other personally and exchanged views on the future of the Old Continent several times.

Otto von Habsburg first met the politician known as the “Father of Europe” before World War II, who was then a Member of the French National Assembly.[3] It was the land of Lorraine that connected them in the first place. Robert Schuman was from Lorraine on the paternal line, and as a young lawyer he also settled there in 1912. Even though his political functions forced him to stay regularly in Paris, he returned almost every week to the vicinity of the French-German-Luxembourgian triple border. In 1926, he bought a house in a small village,

Scy-Chazelles, and it was his real home until his death. Otto von Habsburg, 26 years younger than Robert Schuman, considered it particularly important to promote his family’s Lorraine roots. He considered this region to be a central part of European history and partly a family heritage. Even in 2001, he emphasized that he remembered well his father, King Charles the Fourth saying in 1918: “You can forsake everything if you have to, but never Lorraine.”[4]

The Schuman Declaration – 9 May 1950

Otto von Habsburg and Robert Schuman most likely got to know each other through the mediation of Jean de Pange, Count of Lorraine, French historian-writer, after the Anschluss. Jean de Pange, whose father was a French military attaché in Vienna from 1885 to 1889, showed a special interest in Austria from his youth. He contacted Otto von Habsburg through Count Heinrich Degenfeld-Schonburg. They first met at the Hotel Cayré on the Boulevard de Raspail in Paris. From 1939, the Count of Lorraine supported Otto von Habsburg in organizing the Austrians who had fled to France.[5] Jean de Pange already knew Robert Schuman at this time, who, as a Member of the National Assembly of Thionville in Lorraine, watched the events in Central Europe with great interest. Insomuch that he visited the region three times in the 1930s. He did not travel alone, but with a small group from the French National Assembly, whose destination was Hungary. On the way back home, they made a short visit to Vienna in 1934, and 1935 as well. On both occasions, the delegation was received by the Austrian Chancellor: [6] In 1934 Engelbert Dollfuss, a year later Kurt Schuschnigg. (It is interesting that Schuschnigg met Otto personally ten days earlier in Paris, as the Minister of Culture.)[7]

Robert Schuman was greatly influenced by the journeys in Central Europe and was confirmed that the Western powers had made serious mistakes in the post-World War I peace settlement. In the mid-1930s, the French politician saw the problems as remediable if Paris carried out a radical paradigm shift in foreign policy. Schuman believed that if French and Western European diplomacy did not change towards Central Europe, it would strengthen Hitler’s power and plunge the Old Continent into war. With all this in mind, he was happy to meet Otto von Habsburg to help Austrians who had fled to France after the Anschluss, probably in 1939. This was referred to by the former heir to the throne in the preface of the book published posthumously by Jean de Pange. Here, Otto von Habsburg mentions a meeting in September 1939 when he talked to a friend of the Count of Lorraine about Robert Schuman’s visionary political ideas.[8] Jean de Pange continued to support Austrian refugees after the beginning of World War II, intervening several times with Robert Schuman, who was appointed Undersecretary of State for Refugees in March 1940, on this issue. It cannot be ruled out that this again provided an opportunity for a meeting between Otto von Habsburg and the later French Foreign Minister.

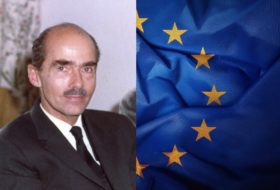

Otto von Habsburg in Paris (around 1954)

(Source: Otto von Habsburg Foundation)

After World War II, the heir to the throne settled in Paris and had the opportunity to contact Robert Schuman, who took on a role in the government. Both were motivated by their belief in the process of European unification. In particular, Schuman, as the head of French diplomacy (since July 1948), considered it his duty to strengthen cooperation and reconciliation in Europe. He followed with great interest the European movements which showed considerable activity in the period, while he was most concerned with the future of German-French relations. He has personally repeatedly expressed his support for the European Movement, which brings together groups fighting for the unity of the Old Continent. He was an active participant in the British-French debates that preceded the creation of the Council of Europe. Although the European institution that was set up in May 1949 did not reflect the idea of Robert Schuman, the French politician nevertheless saw its creation as an important step.[9]

At the same time, Otto von Habsburg, who had been a member of Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-European Union since 1936, also paid close attention to the various ideas that promoted the unity of Europe. The heir to the throne remained in close contact with the leader of the movement established in 1922 during and after World War II, so he was aware that Coudenhove-Kalergi had founded the European Parliamentary Union in 1947. He saw that the leader of the movement had considered the German-French compromise as the first stage in the possible birth of a united Europe. Otto also realized that the founding president of the Pan-European Union was placing increasing emphasis on relations with Christian Democratic politicians in Western Europe, including Robert Schuman.[10] The logical consequence of his close relationship with Coudenhove-Kalergi was that Otto von Habsburg once again sought the opportunity to meet Schuman. This intention was encouraged by the clear development of the Cold War. Otto von Habsburg has consistently stressed that the process of integration in Western Europe must not forget the peoples behind the Iron Curtain. Schuman also maximally shared this view, and even met regularly with personalities who emigrated to France from Soviet-dominated countries (including the resigned Hungarian Ambassador to Paris in 1947, Pál Auer[11]), in order to be properly informed about the situation in these states. Otto von Habsburg, who was also informed on events in the Eastern Bloc, provided valuable news to the French Foreign Minister on this issue. It is no coincidence then that the two personalities found each other again in the 1950s.

Robert Schuman and Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi

(Source: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Bildarchiv)

The meeting was held shortly after the announcement of the plan. This is evidenced by the letter of the heir to the throne, sent to Baron György Bakách-Bessenyey, the former ambassador to Bern (the “Minister of Foreign Affairs” of the Hungarian National Committee set up in New York in 1948).[12] Otto wrote briefly in this letter: “The Schuman Plan made a very significant contribution to the French-American rapprochement.” More than twenty years later, the Lausanne Center for European Research has set out its views on this event in more detail in its publication titled La vocation d’Otto de Habsbourg-Lorraine [Vocation of Otto von Habsburg-Lorraine]:

“On May 9, 1950, Schuman introduced in the French Parliament[13] the idea of a European Coal and Steel Community, the primary aim of which was to bring Germany and France into such an intense economic union that makes war between the two nations never be possible. During this period, great European hopes and suggestions were well received. However, it was not at all acceptable to those who wanted to reach the goal faster. I was also one of those who tried to convince Schuman to take it one step further. It would be unworthy for our Continent to be able to create only a community of an exclusively economic nature. It’s easy to contradict our enemies, but all the harder to say “no” to our friends. Schuman however insisted. He kept trying to explain, with his kindness and humility, that small steps lead to the goal faster than big forward jumps. His determination paid off. Other examples later showed that the Treaty of Rome would never have been signed, we would never have talked about EFTA if partial integration had not broken the resistant front in advance at a defining point. Schuman was successful because he had the courage to recognize certain boundaries.”[14]

The Wedding of Otto von Habsburg and Princess Regina of Saxe-Mainingen (Nancy, 10 May 1951)

(Source: Otto von Habsburg Foundation)

The relationship between the Lorraine politician, revered as the “Father of Europe,” and Otto von Habsburg deepened significantly in the time following the announcement of the May 9 plan. But their correspondence was not only about political issues. In 1951, Robert Schuman helped Otto von Habsburg to organize his wedding in Nancy, the capital of Lorraine,[15] which was held on May 10 of that year. Robert Schuman, though expected among the guests of honour, was unable to travel to Nancy because of his ministerial preoccupations. At the wedding Mass, therefore, an empty chair was reserved in his honour.[16] After the honeymoon, Otto von Habsburg wrote a congratulatory letter to Robert Schuman on June 22, 1951, who had been re-elected in the colours of the MRP (French Christian Democratic Party) in the Thionville constituency on June 17: “your success will delight those who have been able to see, like me, the French, Christian and European work that you have embarked on as Foreign Minister.”[17]

Congratulations letter from Otto von Habsburg to Robert Schuman on the occasion of his reelection as Member of the European Parliament (1951)

(Source: ARS 3/1/298, Fonds Robert Schuman, Fondation Jean Monnet, Lausanne)

In the 1950s, Robert Schuman and Otto von Habsburg remained in regular contact with each other, they often met more than once a year.[18] On such occasions, they shared their thoughts on European integration and political events,[19] as well as on the issues of Austria and the Eastern Bloc. In later interviews, Otto von Habsburg always mentioned speaking of “the father of Europe” that, unlike Schuman, he would have started European unification with culture rather than economy. He always added: “Fortunately, he didn’t listen to me.”[20]

He met Schuman shortly before his death on September 4, 1963, and this last visit deeply impressed Otto von Habsburg.[21] He considered the Lorraine politician awarded the title of “Father of Europe” in 1960 for his European vision and commitment as his master. In connection with the construction of Europe, he regularly recalled an idea of Schuman that touched him deeply: “You don’t have to look for the impossible. It is good to turn our attention to the stars, but do not try to take possession of them.”[22]

Otto von Habsburg and Wilfried Martens at the awarding ceremony of the Robert Schuman Prize (1999)

(Source: European Parliament, Multimedia)

Otto von Habsburg always highly esteemed Schuman and his work. He considered exemplary the Christian faith, which also permeated the public function of the politician, and his persistent but humble demeanour in spite of all difficulties. It is symbolic that Otto later received two awards, named after Robert Schuman: one in 1977,[23] and another in 1999,[24] underlining that, although belonging to a different generation, he is also one of the founders of the united Europe.

Gergely Fejérdy

[1] https://www.cvce.eu/education/unit-content/-/unit/0e04d7f8-2913-4cfc-8dd7-95a2f2e430e1/a5c3ab37-bce9-4e42-9d02-b90f8d1960b1 (Downloaded on: 27.04.2020)

[2] René Lejeune: Robert Schuman une ame pour l’Europe. Paris-Fribourg, Saint-Paul, 1986. 120–121.

[3] Archives of the Otto Habsburg Foundation (HOAL) 1. 2. d. Interviews. Sonstige Artikel, Grussworte, Interviews 1997–2000. 1997-ben Habsburg Ottó által írt üdvözlő szavak Robert Schumanról [Welcoming words written by Otto Habsburg about Robert Schuman in 1997].

[4] Baier, Stephan – Demmerle, Eva: Habsburg Ottó élete [Life of Otto Habsburg]. Budapest, Európa, 2003. 561.

[5] Jean-Francois Thull: Jean de Pange. Un Lorrain au service des Habsburg. Le Pays Lorrain. vol. 95. 2. 2014. June. 180.

[6] Gergely Fejérdy: Les visites de Robert Schuman dans le bassin du Danube. In.: Sylvain Schirmann (ed..): Robert Schuman et les Pere de l’Europe. Culture politique et années de formation. Bruxelles, P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2008. 69–86.

[7] Róbert Fiziker: Habsburg kontra Hitler – Legitimisták az Anschluss ellen, az önálló Ausztriáért [Habsburg v. Hitler—Legitimists against the Anschluss for an independent Austria]. Budapest, Gondolat, 2010. 291.

[8] Otto Habsburg: Préface. In.: Jean de Pange: L’Auguste Maison de Lorraine. Lyon, Imprimeries réunies, 1966. 7.

[9] Poidevin, Raymond: Robert Schuman, homme d’Etat, 1886–1963. Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1986, 230–234.

[10] Baier & Demmerle: op.cit. 355–360.

[11] Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Országos Levéltára [Hungarian National Archives] (MNL OL.) P 2066 2.d. 31. t. 260. Paris, October 31, 1950

[12] MNL OL P 2066 1. d. 25. t. 3. 118–119. Paris, June 26, 1950

[13] Otto Habsburg was wrong to claim this.

[14] Habsbourg, Otto, Pons, Vittorio, Regamey, Marcel & Valynseele, Joseph: La vocation d’Otto de Habsbourg-Lorraine. Lausanne, Centre de Recherches Européennes, 1973. 132–133.

[15] Thull: op. cit. 182.

[16] Dugast Rouille, Michel, Cuny, Henry et Pinoteau, Hervé, Baron: Les grands mariages des Habsbourg. Paris. 1955. 138–139.

[17] Fondation Jean Monnet pour l’Europe (FJME), ARS 3/1/298 : Lettre de Othon d’Autriche-Hongrie a Schuman.

[18] Baier & Demmerle: op. cit. 235.

[19] Alan Paul Fimister: Robert Schuman: Neo Scholasitc Humanism and the Reunification of Europe. Brussels, P.I.E. Peter Lang, 2008. 145.

[20] Interview d’Otto de Habsbourg-Lorraine: la politique des petits pas (Pöcking, 5-6 février 2004). See: https://www.cvce.eu/obj/interview_d_otto_de_habsbourg_lorraine_la_politique_des_petits_pas_pocking_5_6_fevrier_2004-fr-24a10476-97ab-4b34-bb52-42a624d4c841.html (Downloaded on: 27.04.2020)

[21] Habsbourg, Pons, Regamey, Valynseele: op. cit. 133.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Otto Habsburg received the Robert Schuman Gold Medal from the Association des Amis de Robert Schuman [Association of Friends of President Robert Schuman] in Montigny-lès-Metz in 1977, which Jean Monnet presented to Konrad Adenauer 11 years earlier.

[24] In 1999, the Robert Schuman Prize of the European Parliament’s People’s Party was presented to Otto Habsburg by the then President, Wilfried Martens.